The History of Florida (56 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

infinitely better than it was to be for the next seventy-five years.”

headed by Harrison Reed, Wil iam H. Gleason, and Thomas W. Osborn,

among others, took a more moderate position. They realized that congres-

sional requirements would have to be met, but they were more interested in

developing the vast vacant lands of the state. They were willing to include

blacks in the new electorate, but they also wanted the native whites to par-

ticipate in the new government.

The Republicans elected nearly al of the forty-three delegates to the

convention, which met in January 1868, but they were varying kinds of

266 · Jerrell H. Shofner

Republicans. The Radical Republican Billings-Richards faction was able to

control the organization of the convention and seemingly would be able to

write a constitution suitable to them. White delegates sympathetic to Reed

and Gleason bolted the convention and wrote a contesting document with

the cooperation of Charles E. Dyke and McQueen McIntosh, both of whom

represented the native white leadership of the state. They then returned to

Tal ahassee in the middle of the night, took possession of the assembly hal ,

and reorganized the convention while the Billings-Richards delegates slept.

The Radical delegates were dumbfounded that fol owing morning to find

themselves locked out of the assembly hal by a cordon of U.S. soldiers.

After several stormy days and some amazing decisions by Congress, the

moderate version of the constitution—despite its unorthodox origin—was

sent to the pol s and approved by Florida voters. Harrison Reed was elected

governor and William H. Gleason lieutenant governor. At a Fourth of July

ceremony, Colonel John T. Sprague, commander of the occupation force,

relinquished authority to Governor Reed. Radical Reconstruction had led

to a constitution which, according to the new governor, would “prevent a

Negro legislature.”3

Reed’s was a stormy administration. In his continuing effort to retain

the support of native whites for the new government, he appointed Robert

proof

Gamble and James Westcott to cabinet positions, but that move backfired

when Gamble openly opposed Reed’s deficit financing plans. Having sup-

ported him against the Billings-Richard faction, Charles E. Dyke now lev-

eled the powerful guns of his

Tal ahassee

Floridian

against the governor in

particular and all Republicans in general. A sizable minority of native white

legislators calling themselves Conservatives used their votes in the legisla-

ture to thwart Reed and embarrass the new Republican Party. Attempting

to tread the narrow path between Conservatives on one hand and black leg-

islators on the other, the governor angered both. His ambitious lieutenant

governor was not much help either: Gleason supported a move to impeach

Reed and remove him from office. The wily governor bested him, retained

his office, and strengthened his position by appointing Jonathan C. Gibbs,

a capable and influential black, as secretary of state. Gleason subsequently

turned his considerable abilities to developing vacant lands in peninsular

Florida and founding the town of Eau Gallie on the Indian River.

While Conservative editors and legislators fought Reed in Tal ahassee,

others took more direct action in the outlying areas. Control ing most of

the land and credit, Conservative planters and merchants denied credit

and land rentals to freedmen who continued to vote the Republican ticket.

proof

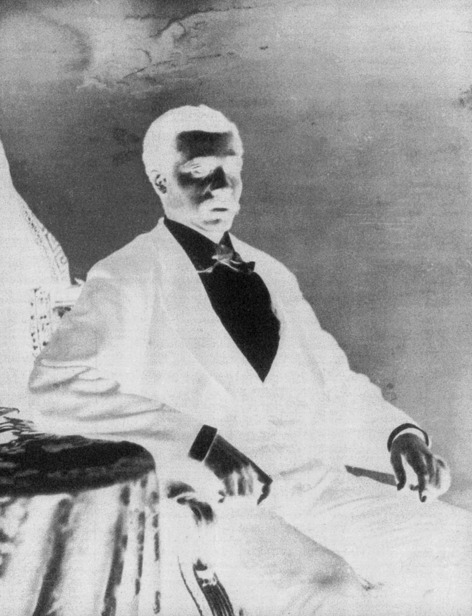

Born a slave in Virginia, Josiah T. Walls served in the Union army and settled in Florida

after Appomattox. Aided by Republican Reconstruction politics, he entered public life

as a state representative and senator. Then, in 1870, he became Florida’s first African

American member of the U.S. House of Representatives, to which he was elected twice

more. Following politics he turned to truck farming. Other black politicians in Florida

during the 1870s were John Wallace, Henry Harmon, Charles Pearce, Robert Meacham,

and the Dartmouth-educated Jonathan Gibbs, who became secretary of state under

Governor Harrison Reed (1868–73).

268 · Jerrell H. Shofner

Vigilantes such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Young Men’s Democratic Clubs

used violence and intimidation to discourage or prevent newly enfranchised

blacks from exercising their voting privileges. Leaders were threatened,

beaten, and kil ed. Pol ing places were disrupted by gunfire and threats.

Former Confederate cavalry commander J. J. Dickison even led bands of

mounted men in cavalry charges through crowds of potential voters. With-

out financial and personnel resources, Reed was obliged to rely on the U.S.

Army garrison to maintain order. But its numbers were smal , it was far

removed from the many scenes of violence, human life was lightly regarded,

the stakes were high, and the violence continued.

Congress ultimately responded with legislation empowering the pres-

ident to restore martial law, but violence and disorder remained serious

problems during most of Reed’s four and a half years in office. Intraparty

factionalism and repeated impeachments of the governor, some of which

were inspired and encouraged by U.S. Senator Thomas W. Osborn, kept

the state in turmoil and discredited both the Reed administration and the

Republican Party.

While Reconstruction brought unwelcome changes and political and

racial strife to the Middle Florida plantation belt, it concomitantly helped

to open up peninsular Florida to settlement. Until the 1860s the Florida

proof

peninsula had been a sparsely populated cattle range where drovers grazed

their herds over miles and miles of open range. When Wil iam Gleason

accompanied Freedmen’s Bureau agent George F. Thompson on a tour of

southern Florida in 1865–66, they reported vast open lands and a balmy

climate—only the first of many touting the Florida peninsula to receptive

audiences across the nation. Northerners were attracted by available open

land where the winters were mild. Southerners liked the idea of an unsettled

region where they could escape the conditions of Reconstruction.

Soon magazines, newspapers, and railroad companies were sending re-

porters to observe and report on this paradise. By 1870 Floridians were pub-

lishing the

Florida

New

Yorker

to attract settlers and investors. Jacksonville,

which had been almost destroyed by the frequent invasions of the war years,

bounced back to become the center of winter tourism, the gateway to south-

ern Florida via the St. Johns River, and a budding financial center where

northern capital was increasingly available for investment. Hubbard Hart’s

line of steamers was one of several which carried passengers and freight up

the St. Johns. He and others made a tourist attraction of Harriet Beecher

Stowe’s winter home at Mandarin, easily visible to passengers eager to catch

a glimpse of the lady who Abraham Lincoln had once credited with starting

proof

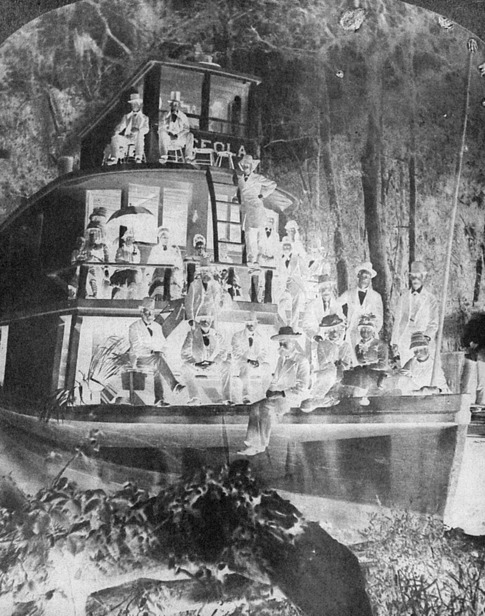

President and former Union general Ulysses S. Grant (

seated,

left

front

) and a party of

northern friends journey down Florida’s most picturesque river, the Ocklawaha, on

the paddle steamer

Osceola.

Similar steamboats plied the St. Johns, Suwannee, and

Apalachicola Rivers. One nervous passenger on the Ocklawaha recorded: “The hull of

the steamer went bumping against one cypress-butt, then another, suggesting to the

tyro in this kind of aquatic adventure that possibly he might be wrecked, and sub-

jected, even if he escaped a watery grave, to a miserable death, through the agency of

mosquitoes, buzzards, and huge alligators.”

270 · Jerrell H. Shofner

the Civil War. But Hart also added a popular tourist attraction by opening

up the Ocklawaha River to Silver Springs, which by 1873 was being visited

by 50,000 tourists annual y.

Frederick DeBary, a Belgian wine merchant, also transported visitors

up the St. Johns as far as Lake Monroe, where he built a hotel at the new

community named for him. The Brock Line operated between Jacksonville

and Enterprise on the northern shore of Lake Monroe. Small shallow-draft

steamers plied the tortuous channels of the upper St. Johns with passengers

and cargo bound for the Indian River settlements of Titusville, Rockledge,

and Eau Gallie. With three large hotels, Rockledge soon became known as

the southernmost winter resort in the nation.

One of the Yankees who invested largely in peninsular Florida was Henry

S. Sanford, a former Union general and powerful member of the national

Republican Party. He founded the town of Sanford about 1870 on Lake

Monroe’s south shore. Using both Swedish immigrant and native black la-

bor, he developed two large orange groves. He also sold numerous tracts to

other northerners, among whom were Wil iam Tecumseh Sherman, Senator

Henry Anthony of Rhode Island, and Orvil e Babcock, personal secretary to

President Grant. With Sanford’s vigorous support, several Boston investors

started the South Florida Railroad to run southward through Orlando to

proof

Kissimmee, thus opening more of the peninsula to settlers. President Grant

was induced to turn the first shovel of earth in 1879.

In the absence of suitable transportation, settlement of the western part

of the peninsula lagged behind the St. Johns River val ey, but Tampa boasted

a few hundred inhabitants near the old Fort Brooke army reservation in

the early 1870s. A colony of “Downeasters” settled at Sarasota in 1868, and

tourists were able to find lodging at several locations in Manatee County by

the early 1870s. Jacob Summerlin, Zibe King, Francis A. Hendry, the Curry

family, and others continued grazing their herds uninterrupted on the south

Florida range, but the citrus and tourist industries were already on their way

during the Reconstruction years.

The missing link was suitable railroad transportation, but the state’s In-

ternal Improvement Fund was unable to use its millions of acres of public

lands as incentive to potential builders because of a complicated lawsuit

that prevented it from conveying clear titles. Efforts in 1866 to revive the

war-damaged Florida Railroad from Fernandina to Cedar Keys had resulted

in a federal court injunction prohibiting sale of state lands except for cash.

Unable to effect such a sale, the state could not clear the so-called Vose in-

junction until 1881. The Reed administration assisted Milton Littlefield and

Reconstruction and Renewal, 1865–1877 · 271

George W. Swepson with their Jacksonville, Pensacola, and Mobile Railroad

venture, but that firm also became embroiled in litigation which was not

settled until 1879. Railroad construction in Florida had to wait until the

1880s.

Events surrounding the Jacksonvil e, Pensacola, and Mobile Company

were catalysts for one of the four attempts to remove Governor Reed from

office by impeachment. These internecine squabbles added to the confusion

that brought Reed’s administration to an end in 1873. A fractious Republi-

can convention bypassed him in 1872 and nominated for governor Ossian

B. Hart, the native Florida Unionist who had good relations with black lead-