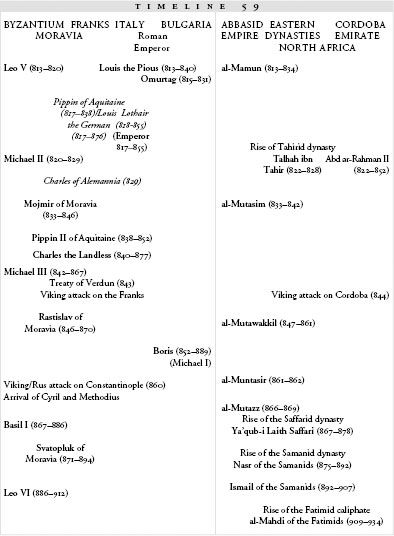

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (60 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

With the complete abdication of any real Abbasid authority at Baghdad, a gash opened across the fractured surface of the Islamic lands.

In the westward lands of northern Africa, known generally to Muslims as “the Maghreb,” Shi’a Muslims had been gathering in greater and greater numbers. These Shi’a Muslims were a particularly militant community. For some decades, the Shi’a had been divided by arguments over the legitimacy of the

imam

; all of them agreed that there should be a designated

imam

leading the Prophet’s people, but figuring out exactly

who

had been designated had proved unexpectedly difficult. All Shi’a agreed that the designated line of Shi’a

imams

began with Ali himself and continued on with his sons, his grandson, his great-grandson, and his great-great-grandson, Ja’far al-Sadiq.

*

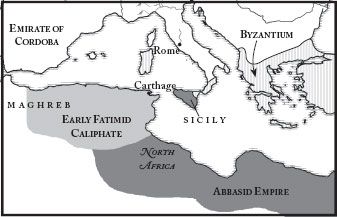

59.2: The Fatimid Caliphate

At that point, the Shi’a had an internal argument. The largest group of Shi’a Muslims insisted that the rightful

imams

were descended from Ja’far’s younger son, Musa, and a smaller group claimed that Ja’far’s older son Ismail had instead been the heir to his power. This smaller group, the Ismailis, were inclined to be more aggressive and warlike in pressing their claims than their Shi’a brothers. From North Africa, they had been watching the charade at Baghdad play itself out. And in 909, the Ismailis offered a candidate of their own for the caliphate: Ubaydallah al-Mahdi, who claimed to be a descendent not only of Ismail but also (tracing his ancestry back a few more generations) of Ismail’s great-great-great-grandmother Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter. Al-Mahdi did not simply make himself emir, like the leaders of the Saffarids and Samanids. Instead, he proclaimed himself caliph in the Maghreb.

This North African caliphate—the “Fatimid” caliphate—was a direct challenge to the authority of the Abbasids. Until this point, all of the fragments of the Islamic empire had been painted the same color; even the Umayyad emir in al-Andalus had declined to call himself a caliph; even the Saffarid and Samanid rebels had paid lip service to the Abbasid caliphate.

But now, three hundred years after Muhammad, the Islamic world had cracked irreparably into two. The “Islamic empire” had been a convenient myth for over a century. Now it was not even possible to speak of it. There was no empire based on religion in the east, any more than in the west: simply a collection of nations and states, each fighting for survival.

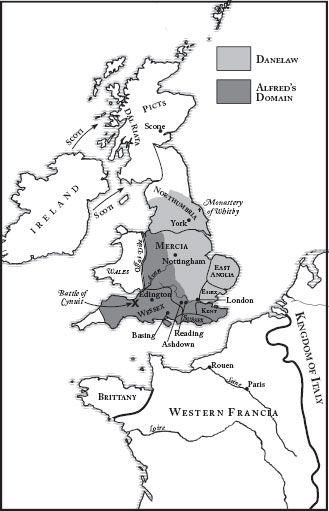

Between 865 and 878, Alfred of Wessex makes peace with the Vikings by dividing his island with them

I

N

865,

A DETACHMENT

of the Vikings who had been pillaging the lands of the Franks sailed away from the fortified bridges of Charles the Landless and followed the sea to easier country.

Across the water from Western Francia lay the island of Britain, covered with an uneasy network of kings and warleaders. Since Roman times, Pictish tribes in the north had struggled with the Scoti—pirates from the western island of Ireland who had landed on the cold mountainous shores and rooted themselves in. Farther south, seven Anglo-Saxon kings divided up the English countryside.

*

The craggy southwestern coasts remained in the hands of the Welsh, descendents of the Romans and Irish and native Britons who had settled there since the days of the fourth-century Roman general Magnus Maximus. Between the central kingdom of Mercia and the kingdom of Wales lay a massive fortification built by the eighth-century Mercian king Offa, a great ditch in front of a twenty-foot wall of earth. “The Welsh devastated the territory of Offa,” says the thirteenth-century

Chronicle of the Princes

, “and then Offa caused a dike to be made, as a boundary between him and Wales; it extends from one sea to another.”

1

The previous century had seen several attempts at unification. Some twenty years before the Viking invasion of Britain, Cinaed mac Ailpin, ruler of the Scoti kingdom Dal Riata on the northwestern coast, attacked the Picts to his east. He folded their land into his own, creating a kingdom that stretched across the north. Cinaed mac Ailpin was later known as Kenneth MacAlpin or Kenneth I, the first king of Scotland; his dynasty, the House of Alpin, ruled over this united northern kingdom from the city of Scone.

2

60.1: Offa’s Dike, photographed in the 1990s near Knighton in Wales

Credit: Homer Sykes/Corbis

In the south, the Mercian kings who came after Offa had managed to dominate the eastern kingdoms of Kent and East Anglia for a time, but both soon broke away. By 860, Mercia had declined in power and Wessex had ascended: the king of Wessex had annexed both Kent and Sussex, and the southeast of England was more or less united under a single throne.

3

But there was still no high king who could pull the divided Anglo-Saxon forces together in resistance to the Vikings.

The Vikings who arrived in 865 landed in Wessex. They were under the command of three brothers: Halfdan, Ivar, and Ubbe, sons of the Viking pirate Ragnar Lodbrok himself. The oldest brother, Ivar, was known as Ivar the Boneless. He may have been the victim of a bone disease that weakened his legs; all we know for certain is that he was often carried on a shield into battle, where he fought with a long spear. His arriving hordes flew the Raven Banner, the symbol of the god Odin.

Odin, king of battles, could blind and deafen his foes. He could still the sea and turn winds to give victory; he could awaken the dead, and his two ravens flew over the land and brought him intelligence of his enemies. “It is told,” wrote the ninth-century Welsh monk John Asser, “that the three sisters of Ivar and Ubba wove that banner, and completed it entirely between dawn and dusk on a single day. Moreover they say that in every battle in which that banner goes before them, the raven in the midst of the design seems to flutter as though it were alive, if they were destined to gain the day; but if they were about to be conquered, it would droop down without moving. And this has often been proved to be true.”

4

The Raven Banner was more than a standard. It was a sign of the ancient religions whose power still lingered in the memories of the Christian Anglo-Saxons. England had been officially Christian since 664, when the Northumbrian king Oswiu called a council at the monastery of Whitby and announced that his kingdom would join the rest of the Christian world in “one rule of life…and the celebration of the holy sacraments.” But the faith itself had spread unevenly. As long as the country remained a quilt of independent political allegiances, ninth-century Christians carried out their devotions separately, with the old British religions still practiced in the mountains and crags of Wales, in the deep patches of forest that lay between villages, in the darkness that surrounded the struggling churches of Wessex and Mercia and Northumbria.

5

In the old English epic

Beowulf

, which reflects a ninth-century world, a Christian king and his warriors live on top of a well-lit hill, but a monster prowls through the tangled swamps below: a demon, a kinsman of Cain, an enemy of God. He haunts “the glittering hall,” attacking at night to drag the warriors away into the heathen darkness. “These were hard times,” the poet says; the threat of the monster’s attack even drove the warriors back to pagan shrines, where they made offerings to the old gods in hopes of deliverance. “That was their way,” the poet writes, “their heathenish hope; deep in their hearts they remembered hell.”

6

By the time

Beowulf

was written down, a century or so later, the Vikings were rooted deeply into the Anglo-Saxon countryside, and the Christian king was himself of Viking blood. But in 865, the Viking invaders—the Great Army of the Vikings—were part of a hellish attack: warriors from the old world, with the god’s demons on their banners. Their victory would not merely deprive the Anglo-Saxons of land. It would pull them back into the dark waters of the ancient religions.

Ivar the Boneless and his men first landed in East Anglia, where their overwhelming might forced the East Anglian king into quick agreement: in exchange for keeping his throne, he would provide food and shelter over the winter and horses in the spring. The Great Army spent the winter of 865 in their East Anglian haven, and when the worst of the cold was over, began the march north into Northumbria.

7

Northumbria had been divided by civil war between two men who claimed the throne, but at the Viking approach they gave up their struggle, united their forces, and turned together to face the new threat. Their cooperation was too little, too late. By the end of 867, the Great Army had overrun Northumbria, taken York, and laid waste to the monastery at Whitby. It would lie wrecked and ruined for the next two hundred years. “An immense slaughter was made of the Northumbrians,” the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

tells us, “and the same raiding-army [then] went into Mercia.”

8

The king of Mercia sent to his neighbor, King Ethelred of Wessex, for help. Ethelred, who also controlled Sussex and Kent, answered the call. Together with his younger brother Alfred (now about twenty years old, serving as Ethelred’s second-in-command), King Ethelred came to meet the Vikings at Nottingham, and there arranged a temporary peace: “No heavy fight occurred there,” the

Chronicle

says, “and the Mercians made peace, and the raiding-army went back to York and stayed there one year.” Probably Ethelred and Alfred paid the Vikings off; in exchange for saving Mercia, young Alfred got the daughter of the Mercian king as his wife, which essentially promised him the kingdom of Mercia at some point down the line.

9

At the end of that year, having regathered their strength (and restocked their provisions), the Vikings went back into East Anglia, killed the king who had provided them with winter quarters, and took it for themselves. Now they were masters of the north and part of the east, and Wessex itself was in danger.

The Great Army marched into Wessex during the winter, in January of 871. Ethelred and Alfred braced themselves for the attack, but despite their resistance, the Vikings moved steadily westward into Ethelred’s kingdom. On January 4, the Anglo-Saxon army was defeated at Reading in Sussex. The soldiers retreated and retrenched. Four days later, they met the Great Army again at Ashdown. This time they were able to push the Vikings back, but Ethelred’s army was seriously weakened by the victory: “There were many thousands killed, and fighting went on until night,” the

Chronicle

tells us.

10

Two weeks later the tide turned back towards the Vikings, and in another enormous clash at the southern town of Basing, the Great Army was victorious. Halfdan took over the rule of London, and Viking reinforcements arrived to swell the Great Army’s ranks.

Although Ethelred continued to resist, he died of illness in April, aged thirty. Alfred, now in his early twenties, inherited the kingship of Wessex, the command of the struggling Anglo-Saxon army, and the unenviable task of meeting the Great Army in battle. “He was a great warrior and victorious in virtually all battles,” wrote his contemporary John Asser: this is clearly hindsight, since Alfred promptly lost another fight against the Great Army and was forced to make a temporary peace treaty.

Meanwhile, the Vikings firmed up their dominance in Northumbria, and then in 874 moved back into Mercia and took the kingdom for their own. At some point during these months of battle, Ivar the Boneless died; but the Vikings continued strong, led by Ivar’s brother Ubbe (Halfdan had fallen out of favor with his followers, thanks to his ruthlessness) and by Ubbe’s lieutenant, the warrior chief Guthrum.

It seemed to be only a matter of time before the entire island fell into Viking hands. So Alfred, in command of an exhausted and ravaged army, went into hiding. He had watched Ethelred fight battle after battle at the cost of thousands of lives, and could see no future in continuing a war of attrition. By 878, Anglo-Saxon refugees were sailing away from the island, looking in desperation for new homes; the Vikings were camped firmly on the Avon; and Alfred and his men were far out of sight, living in the swamps of Athelney in Alfred’s Wessex kingdom. “He led a restless life in great distress amid the woody and marshy places,” writes Asser, “…[with] nothing to live on except what he could forage by frequent raids…from the Vikings.”

11

All was not yet lost. He was not the only general leading attacks against the Vikings; in early 878, Ivar’s brother Ubbe was killed in the Battle of Cynuit, possibly on his way to try to flush out Alfred’s army. The Anglo-Saxon forces were led in this fight by the nobleman Odda, a Saxon ealdorman (or alderman, a

dux

who governed in the king’s name), who not only triumphed over the Vikings but also captured the Raven Banner, the sign of Odin’s power.

Perhaps this good omen heartened Alfred, but he didn’t come out of hiding. Guthrum was still at the Great Army’s head, and the Vikings were still in control of the countryside. Alfred had decided to take the long view: he was willing to risk the kingdom so that he could build up his fighting force. Stories would later multiply around this self-imposed exile, including the most famous tale of all: Alfred, hiding out incognito in the hut of an Athelney cowherd, was told by the housewife to watch the cakes baking on the hearth. Preoccupied with thoughts of his war against the Vikings, he ignored the cakes when they began to burn, and the housewife came storming back into the hut. “You’re anxious enough to eat them when they’re hot!” she scolded, “why can’t you turn them when they’re burning?”

12

This story was inserted by the sixteenth-century clergyman Matthew Parker, who claims that it was found in a ninth-century source; it probably arose later, but its essence tells us something about the memory of Alfred, who humbly turns the cakes and doesn’t reveal to the housewife that she has just told off the king of England. Even his contemporaries saw him as virtuous and holy, a God-provided deliverance from the pagan threat: which is why John Asser characterized him as victorious even when he was losing, and why the later chronicler Simeon of Durham insisted that his face shone like an angel’s, and that his armor was faith, hope, and the love of God.

13

60.1: The Treaty of Wedmore