The History of White People (15 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

Jefferson’s Saxon genealogy ignored a number of inconvenient facts. The oppressive English king George III was actually a Saxon and also the duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg as well as elector of Hanover in Lower Saxony. Furthermore, George III’s father and grandfather, Hanoverian kings of England before him, had been born in Germany and spoke German as a first language. It hardly mattered. To Jefferson, whatever genius for liberty Dark Age Saxons had bequeathed the English somehow thrived on English soil but died in Germany.

*

In the Philadelphia Continental Congress of 1776, Jefferson went so far as to propose embedding his heroic Saxon ancestors in the great seal of the United States. Images of “Hengist and Horsa, the Saxon chiefs from whom we claim the honor of being descended,” would aptly commemorate the new nation’s political principles, government, and physical descent.

9

*

This proposition did not win approval, but Jefferson soldiered on. In 1798 he wrote

Essay on the Anglo-Saxon Language

, which equates language with biological descent, a confusion then common among philologists. In this essay Jefferson runs together Old English and Middle English, creating a long era of Anglo-Saxon greatness stretching from the sixth century to the thirteenth.

With its emphasis on blood purity, this smacks of race talk. Not only had Jefferson’s Saxons remained racially pure during the Roman occupation (there was “little familiar mixture with the native Britons”), but, amazingly, their language had stayed pristine two centuries after the Norman conquest: Anglo Saxon “was the language of all England, properly so called, from the Saxon possession of that country in the sixth century to the time of Henry III in the thirteenth, and was spoken pure and unmixed with any other.”

10

Therefore Anglo-Saxon/Old English deserved study as the basis of American thought.

One of Jefferson’s last great achievements, his founding of the University of Virginia in 1818, institutionalized his interest in Anglo-Saxon as the language of American culture, law, and politics. On opening in 1825, it was the only college in the United States to offer instruction in Anglo-Saxon, and Anglo-Saxon was the only course it offered on the English language.

Beowulf

, naturally, became a staple of instruction. Ironically, the teacher hailed from Leipzig, in eastern German Saxony. An intensely unpopular disciplinarian, Georg Blaettermann also taught French, German, Spanish, Italian, Danish, Swedish, Dutch, and Portuguese. After surviving years of student riots and protests, Blaettermann was fired in 1840 for horsewhipping his wife in public.

11

J

EFFERSON’S ENTHUSIASM

for teaching Anglo-Saxon stayed confined to southern colleges until the 1840s, and his

Essay on the Anglo-Saxon Language

, a rambling 5,400 words composed mostly in 1798, did not appear in print until 1851.

*

Clearly, slavery and the characteristics of black people were stirring more passion than any American claim to Anglo-Saxon ancestry. By contrast, Jefferson’s

Notes on the State of Virginia

(1784) immediately enjoyed a wide and impassioned readership. This eloquent, though very self-centered, summary of American (not just Virginian) identity, impugns the physical appearance of African Americans and makes them out to be natural slaves. Not that this insult toward an oppressed people inspired only approval. One of a multitude of critics resided at the most Virginian of northern colleges: the College of New Jersey.

H

ANDSOME, ELEGANT

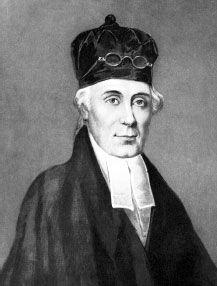

Samuel Stanhope Smith (1751–1819) became president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton College) at forty-three, its first alumnus president. (See figure 8.2, Samuel Stanhope Smith.) Both of Smith’s parents had strong Princeton connections: his mother’s father had been a founding trustee, and Smith’s father, a Presbyterian minister and schoolmaster, also served as a trustee. Smith graduated from Princeton with honors in 1769. As a tutor and postgraduate student with John Witherspoon, an eminent scholar from Scotland, Smith imbibed the “Common Sense” ideals of Scottish realism.

Following an established Princeton trajectory, Smith went south to Virginia as a missionary and became rector and then president of the academy in Prince Edward County that became Hampden-Sydney College. His future secure, he married John Witherspoon’s daughter and bought a plantation, evidently intending to remain among his appreciative Virginia hosts. However, a Princeton professorship in moral philosophy lured Smith back to New Jersey.

Ensconced once again in Princeton, Smith collected the young nation’s honors: Yale made him doctor of divinity in 1783, and in 1785 the American Philosophical Society took him into its membership. After Thomas Jefferson proposed a measure advocating widespread primary education in Virginia in 1788, he and Smith exchanged letters in its support. The measure did not pass, and the politics of the two men subsequently diverged. By 1801 Smith had turned politically conservative enough to deplore Jefferson’s presidential candidacy as likely to cause “turbulance [

sic

] & anarchy.”

12

By then Smith had succeeded his mentor Witherspoon as president of Princeton, and had turned into an intellectual maverick, downgrading the college’s classics and Presbyterianism in favor of science, thereby antagonizing its trustees.

13

As Smith grew older and Princeton students more rowdy, he expelled three-quarters of the student body for rioting in 1807. When the Presbyterian Church established a theological seminary right inside the college’s Nassau Hall, Smith grasped just where his lack of orthodoxy was leading. In 1812 he was forced to resign the presidency, and he died seven years later.

14

All that lay ahead in 1787, when he addressed the American Philosophical Society on differences in skin color, and his star was still ascendant.

S

MITH’S ADDRESS

looked back to the polygenetic essay of a Scottish philosopher named Henry Home, Lord Kames, entitled

Discourse on the Original Diversity of Mankind

(1776). One of Kames’s main points was a rejection of biblical doctrine that traces the unity of humanity through descent back to a single originating couple. Smith disagreed with Kames. Every people did belong to the same species, and differences sprang from circumstance: “I believe that the greater part of the varieties in the appearance of the human species,” Smith declares, “may justly be denominated habits of the body.” Where people live, not their ultimate ancestors, explains variations in human skin color: “In tracing the origin of the fair German, the dark coloured Frenchman, and the swarthy Spaniard, and Sicilian, it has been proved that they are all derived from the same primitive stock.”

15

All mankind descended from Adam and Eve, subsequently diverging though adaptation.

Fig. 8.2. Samuel Stanhope Smith as president of Princeton College.

Smith’s defense of biblical truth met so warm a reception that the lecture appeared immediately in print. Mary Wollstonecraft, the feminist pioneer, favorably reviewed Smith’s

Essay

in the London

Analytical Review

, welcoming his insistence on the unity of mankind. Smith’s distinguished physician-historian brother-in-law, David Ramsay, a Pennsylvanian living in South Carolina, pitched in. Ramsay seconded Smith’s views on skin color, lauded his criticism of Thomas Jefferson’s antiblack slurs, and agreed with Smith about the dominance of climate in shaping human culture. Writing directly to Jefferson, Ramsay noted that “the state of society” also plays a crucial part. In complete agreement with Crèvecoeur and Smith, Ramsay added, “Our back country people are as much savage as the Cherokees.”

16

*

Jefferson seems not to have replied to Ramsay. But encouraged by support, Smith continued tinkering with his

Essay

.

One influence was Blumenbach’s 1795 edition of

De generis humani varietate nativa

, which Smith read in its original Latin and incorporated into an enlarged 1810 edition of his lecture,

An Essay on the Causes of the Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species

.

17

Here Smith assumes that civilization, not barbarism, was humanity’s original condition; uncivilized people would have regressed on account of their harsh living conditions. Different climates, for instance, create differences in human skin color—not a new explanation. Beauty is not all that important, in any case, Smith goes on to say, citing the physical attractiveness of even some black people: “In Princeton, and its vicinity I daily see persons of the African race whose limbs are as handsomely formed as those of the inferior and laboring classes, either of Europeans, or Anglo-Americans.”

A bit—but only a bit—of a cultural relativist, Smith recognizes more emphatically than Blumenbach or Camper the cultural specificity of beauty ideals: “Each nation differs from others as much in its ideas of beauty as in personal appearance. A Laplander prefers the flat, round faces of his dark skinned country women to the fairest beauties of England.”

18

Meanwhile, as we have seen, anthropologists of the time were debating whether Lapps in the north of Sweden and Finland might count as Europeans at all. Linnaeus, the great taxonomist, for instance, said no; Blumenbach, Germany’s leading racial classifier, wavering, said yes. Eventually the question faded into insignificance as anthropology’s terms of analysis moved away from questionable attempts to rank order of physical beauty.

We should note that Smith was no multiculturalist. His Americans, like Crèvecoeur’s, descend only from Europeans. While acknowledging the presence of Native Americans and Africans on American soil and occasionally comparing the height of Osage Indians to that of the ancient Germans, Smith had no intention of widening the category of

American

.

Thomas Jefferson and Samuel Stanhope Smith had both prospered in a Virginia of many mixed-race people, some right in Jefferson’s own family. We do not know the makeup of Smith’s household in Virginia, but we do know that the two men figured the notion of purity differently. Jefferson somehow kept the rainbow people of Monticello beyond the reach of his race theory, allowing him to conceive of a platonic “pure and unmixed” Saxon ideal. For Smith there could be no such European thing, “in consequence of the eternal migrations and conquests which have mingled and confounded its inhabitants with the natives of other regions” in a continuing process of perpetual change.

19

Smith and Jefferson found words for purity and mixture in Europe, even among Europeans in the New World. But the African-Indian-European mixing occurring right under their noses in eighteenth-century Virginia overwhelmed their rhetorical abilities. The leaders of American society could not face that fact squarely. For them mixing produced a unique new man, this American, but mixing only among Europeans.

So if climate is paramount, what of the American climate, with its extremes of heat and cold and its stagnant waters? Not much good comes of it, Smith feels, for it imparts to Americans “a certain paleness of countenance, and softness of feature…in general, the American complexion does not exhibit so clear a red and white as the British, or the German. And there is a tinge of sallowness [paleness, sickliness, yellowness] spread over it.” Elevation and proximity to the sea also affect skin color. Hence the white people of New Jersey have darker skins than white people in hilly Pennsylvania. White skin darkens farther south. White southerners, especially the poor, living in a hot climate and at lower elevations, are visibly darker than northerners. Americans living in different climates look different, but, all in all, Americans look pretty much the same.

20

To justify his tortured climatic theories, Smith has to practice a sort of wild conflation of climate to skin color to savagery. Even when all their ancestors were European, Smith finds that lower-class southerners look very much like Indians and live in a “state of absolute savagism.” This idea, that living among Indians made white Americans resemble them in skin color, enjoyed wide currency in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Crèvecoeur exclaimed that “thousands of Europeans are Indians,” and others in colonial America testified to the tendency in Europeans living with Indians to come to resemble them in color as well as in dress. Moreover, such a life rendered their bodies so “thin and meagre” that their bones showed through their skin. Had poor southerners been discovered in some distant land, Smith surmises, polygenesists would display them as proof of multiple human origins.

21

Echoing Crèvecoeur, Smith calls uncivilized poor southerners—“without any mixture of Indian blood”—a potential drag on American society.