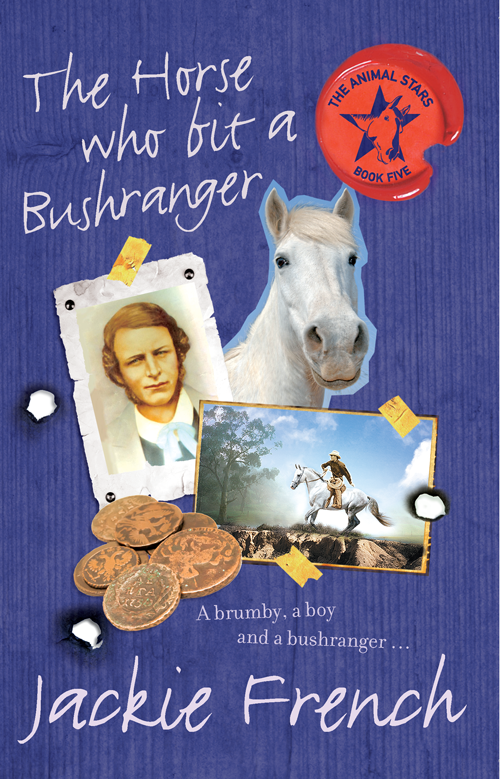

The Horse Who Bit a Bushranger

Read The Horse Who Bit a Bushranger Online

Authors: Jackie French

CHAPTER 4 The Convict Billy, Sydney Harbour, 1831

CHAPTER 50 The Bushranger Ben Hall, April 1865

CHAPTER 51 Mattie Jane, May 1865

CHAPTER 52 Rebel Yell, May 1865

CHAPTER 53 Rebel Yell, May 1865

CHAPTER 55 Rebel Yell, May 1865

CHAPTER 57 Rebel Yell, May 1865

CHAPTER 58 Rebel Yell, 5 May 1865

CHAPTER 59 Ben Hall, 5 May 1869

CHAPTER 60 Rebel Yell, 5 May 1865

CHAPTER 61 Rebel Yell, 6 May 1965

This is a book about racism, set in racist times. This means there are two racist words used several times in this book. I apologise for using them. They are horrible words, but are needed to show the tragedy words like that can bring when people use them.

The Horse, 1830

I remember the day I became the King.

It was the sort of day when you feel the sun on your back, and the breeze your tail makes when you swish away the flies. Fallen branches like twisted brown snakes lay across the ground. The grass tasted of roo droppings, and the sky was white with dust.

Suddenly I scented something. Dingoes had howled from the trees the night before. But that wasn’t what made me stamp and snuffle now.

I lifted my head. There was the smell of wombats, sugar gliders nibbling blossom, kookaburras nesting in tree hollows. There was the scent of something else as well…

Mare.

Grey Girl’s foal pranced around her mother. It was time for Grey Girl to mate again. As I watched, Highest trotted toward her.

Highest had been King horse all my life. He was a giant bay stallion, with long strong legs and a small

fine head. Grey Girl was the same colour as me, but her foal was bay like Highest.

I was a big horse, the biggest of all the colts. Highest was even larger, with shiny muscles on his chest and legs. But suddenly I pawed the ground and gave a yell of challenge.

Even as I whinnied I knew that I was foolish. There was no way I could win a fight with Highest. I should wait till I was older, stronger. But I couldn’t stop myself.

Highest glanced my way, and then ignored me. He bit Grey Girl lightly on her neck. She swished her tail.

I neighed again, rearing up so my front legs scratched the air. This time Highest looked at me properly. He tossed his head, pawed the ground then trotted up to me with big, high paces, his tail raised like a banner. I could smell his anger and contempt.

The mares glanced up, then went back to their grass. I knew what they were thinking: another young horse, thinking he can beat the King. A few whinnies, some biting, and it would be over. I’d know my place again, and canter off to the edges of the mob, my head down in case Highest grew too angry and chased me off. Then Highest would tend to the mares.

My

mares.

Suddenly the urge to fight was so strong I could think of nothing else. We circled each other, each whinnying a challenge. Suddenly Highest lunged, biting me on the neck.

This wasn’t the soft bite he had given Grey Girl. I felt the hot sting of blood.

I reared, trying to tear his shoulders with my hoofs, but he reared too. He was so tall I couldn’t get close

enough to hurt him. His hoofs looked massive, looming down toward me. One ripped across my back.

Dimly I heard White Foot, our lead mare, neighing at me to give way. Another wound like that might leave me crippled, limping to keep up with the mob. But it was as though a rage had covered me in black night. I reared again.

Highest rose too, but this time he stumbled. He had backed into a wombat hole. The King screamed in agony.

My hoofs came down, striking against a rock. I lunged. This time my hoofs struck him a glancing blow, my teeth seeking his neck. But Highest evaded me, his anger still overcoming his pain. He tried to rise.

The mares were gathered around at a safe distance now, uncertain. A few colts whickered anxiously.

Highest lurched to his feet. He breathed in great deep pants. Something had torn in his leg so he could hardly move. His brown eyes stared at me in agony as well as fury. He tossed his head—a last attempt to threaten me.

Then all at once he dropped his gaze. He hobbled side-on to me, admitting his defeat.

I’d won! I rose on my hind legs, pawing the air, neighing my victory. I knew I did not have to strike him again.

I cantered over to the stream and drank, giving Highest time to look away before I trotted back toward the mares. I could feel their eyes on me, admiring.

Highest gazed down at the tussocks, his skin damp with pain.

And I?

I was the King.

It was grand to be the King.

I could gallop across the grasslands, stamping and neighing, swishing my tail, and know no horse was going to whinny a challenge. I was the biggest, the strongest. I owned the world.

Even the rain seemed to fall at my command that season, so gently we hardly knew it was damp, sheltering under the trees. White Foot led us to lush grass dappled with crunchy flowers, while I kept guard behind. The foals danced about us on their skinny legs. They were all grey like me now. They grew stronger and fatter every day, learning to avoid tripping in the bettong nests that tied the tussocks up into a knot, or the hollows dug by bandicoots.

One night a dingo slunk between our trees, but I lashed it with my hoofs. It darted away, yelping. Sometimes an eagle or a goshawk inspected us as they soared above our heads, but our foals were too strong and healthy to be food for birds. Sometimes, after a lightning storm, bushfire smudged the horizon, but never close to us.

Highest stayed with us for a while, on the edges of the herd, stumbling to keep up. Then one morning in another summer’s dying days, he was no longer there. It is a bitter thing, to watch a young horse take your place. Later that day Grey Girl wandered off, as well.

She was with Highest. The two of them would manage on their own now, away from the mob. Perhaps when Highest died Grey Girl would come back.

But Highest wouldn’t return. Never, while I was King.

The Horse, 1831

I heard the beat of their hoofs before I saw them. But this mob didn’t gallop like free horses.

These horses were ridden by men.

The kookaburras screamed a warning; a white cloud of cockatoos lifted into the sky. I whinnied an alarm call, rising onto my haunches to make sure the others knew how serious this was.

Suddenly the pack of horses appeared over the hill, the men on their backs lashing long hard tails against the horses’ sides, or cracking them in the air. The men yelled. The horses’ heads were down.

They headed straight for us.

I neighed a challenge. White Foot took off, her hoofs raising dust, leading our mob down into the gully. She leapt across the creek. We followed her, a mob of brown and grey backs, moving almost like one horse.

Our hoofs thundered up the hill. I could hear the men’s horses panting behind. None of them were as big and strong as me. Even our youngest foal could outrun

them. We were fresh. We had no men heavy on our backs. There was no way those men could catch us!

I would have whinnied in triumph if I could have spared the breath. Once over this hill we would be free.

My hoofs struck sparks on the rocky ridge. White Foot and the others were almost at the bottom of the gully. Suddenly I halted, panting and staring down.

The bottom of the gully was barricaded with saplings, and white stuff threaded through the trees. More men came riding down the other wall of the gully.

We would be trapped! I neighed another warning. The mob had to gallop back up to me! We could work our way along the ridges, the only way that was free of men.

But it was too late. Even as I called, White Foot stopped, bewildered, men and horses all around her. She whinnied up to me. A foal screamed in terror.

Just for a moment I hesitated, there up on the hill. I could gallop off without the others. They were caught, but I could still be free.

Like Highest, alone without the mob. Maybe I’d find a lone mare like Grey Girl to join me, or another mob. I could challenge the leader and be King again.

But those were my horses down below, terrified and stumbling as the men yelled and lashed around them.

I rose up on my hind legs and trumpeted, just to show I was still free. And then I cantered down to join the others.

I felt the sting of one of the long leather things against my hindquarters. I ignored it. I had let them capture me. I was still the King.

The Horse, 1831

They herded us along the gully, dry after the summer’s heat, the river shrunk to pools of water full of frogs. At last we came to a blind canyon with cliffs on three sides, and rocks tumbled to the ground. And horses, a sea of horses, crammed between the cliffs.

I had never seen so many horses; they had almost no room to move at all.

We stumbled in among them—slowly, for we were tired. But I had the strength to call out, to see if any of the other stallions might challenge me.

No one did. It seemed I was still the King. But King of what? Could a horse held by humans be a king?

White Foot and I kept the other horses away as one by one our mob drank from the pools. There was no grass left. The other horses must have been here for days. The ground was thick with droppings.

I looked and smelt and searched for some way out. The cliffs were too steep, and the men had put up

another barrier between them, bushes tied together with that long white stuff so that we couldn’t pass.

And so we waited, there in the canyon, to see what the men would do next.

The Convict Billy, Sydney Harbour, 1831

Two hundred and sixty convicts had sailed from Portsmouth. Billy reckoned more’n half had died, down here in the stinkin’ darkness of the ship. Some coves had starved, too weak to grab their rations when the bucket swung down from the small square of light that was the hatch, the only light the convicts saw. At least Billy were young, strong enough to grab his rations.

Some coves had died when the waves battered the ship as it sailed around the Cape, knocked from their bunks, lyin’ stunned in the filthy water what washed below their beds; drownin’ in the darkness; only discovered when their bodies floated up and began to swell and stink.

Most had died when the fever came aboard at Cape Town. At first Billy tried to count the bodies as they was hauled up to the hatch on ropes. But then

he caught the fever too—not bad, just enough to lie sweatin’ on his bunk, while Jem brought him food and water. He’d have died if it ha’n’t been for Jem.

The food and slops buckets only came down once a day now. Billy hoped there was enough sailors left alive up there to sail them to Sydney Town.

That’s what you did, down here in the darkness with the rats and the water and the bodies that bobbed up at you from the depths: you hoped—cos there was no way of knowing. You hoped no great wave would send you to the bottom; that no sea monster would swallow the ship; that you’d live, while others died of fear; that one day you’d stand in the sunlight once again.

The convicts was counting the days to Sydney Cove now, though no one knew what cove had begun the rumour they was nearly there…Only three days more, if the wind held good. Two days. One day…

Billy were lyin’ on his bunk with Jem, tippin’ his head to try to drink his stew, tryin’ not to let any of the precious drops spill as the boat swayed, when one of the sailors yelled up on deck.

‘Land ho!’

Jem nudged him in the darkness. He were two years older than Billy, and had been studying at Master Higgins’s school for years—already one o’ the best pickpockets on the streets—when Master Higgins had bought Billy from the workhouse, and had told Jem to learn the new boy his street cons.

They’d made a good team, him and Jem. Billy looked all small and sweet. He’d offer to hold a cove’s horse while Jem nicked his dabs, then they’d scarper afore the peelers could get ‘em.

You got schooled in lots o’ things in Master Higgins’s big attic, even the bridle con. Just about every young pickpocket dreamt of goin’ on the bridle con, bein’ a highwayman and sittin’ on a great black horse and holdin’ up the coaches.

Master Higgins was the best fence in London too. Even flash coves like Gentleman Harry brought their loot to Master Higgins to get the fairest price for the watches or diamond rings. You never got conned by Master Higgins—not when you was on the game, like them. Thieves watched out for their own.

It were a good time at Master Higgins’s. Better than the workhouse, where all you got was slops and beatings. It had been the workhouse for him after Ma and Pa—

Billy shut his mind to life with Ma and Pa. Some things hurt too much to remember. His real life had begun when Master Higgins bought him at the workhouse, telling the matron as how young Billy were to be trained as a chimney sweep.

But there’d been no stinkin’ chimneys for Billy. Instead he had his own pallet of clean straw and a couple o’ blankets too in the big attic warmed by the hotel’s fire downstairs, and super grub. Stew twice a day with real bits o’ meat, not like the slop here on the ship; meat pudding Sundays; bread and cheese for supper and a whole barrel o’ wrinkled apples at Christmas time. Ah, it were good to remember what food could taste like. He and Jem had even shared an orange once.

Jem were more than a friend. They was partners, sharing everyfink they got. The peelers had only pinched ‘em twice, and both times they’d got off,

looking up innocent-like at the magistrate, saying it were all a mistake, they was good boys, and Master Higgins getting coves what talked posh to give them a character, and say what fine lads they really were.

But not that third time. The last time he and Jem had been afore the magistrate they’d both got seven years. Two had already passed. One year before they sailed, in a prison sharing mouldy straw with rats; nearly a year on this tub, where the rats scuttled above you in the darkness. Sometimes Billy heard them gnawing at the wood and wondered if the whole ship was going to sink just cos the rats was hungry…

Billy and Jem had shared a rough plank bunk when they’d sailed from Portsmouth, the dirty water of the hold swishing dark and oily below them. So many had died that there were enough beds for each convict to have his own now. But he and Jem still lay on Billy’s bunk together most times (the bunks were piled too close together to have room to sit up), talking and remembering old times.

Talking with Jem kept the darkness away, and the nightmares too. You had to do something in the long months of the voyage, or you’d lose your wits. Some o’ the men sang, long laments or sea shanties; others stole the metal spoons and stamped down on ‘em hard to make a blade so they could carve out trinkets to sell or keep in memory of those they’d left back home. Others just lay in silence, or muttered in the endless night that was the voyage.

‘Soon be there,’ said Jem. He’d been saying that for days now. But this time it were true.

‘Aye.’ Billy tried to sound optimistic. What would happen when they got to Sydney Town? None o’ the

convicts knew; nor the sailors neither. The ship ha’n’t been on this run before. Another prison? Why ship convicts all the way across the world just to change one gaol for another?

‘We’ll be right. We always ‘as been. Long as we sticks together.’ Jem’s voice was comforting. ‘Hey, you remember Flash Harry?’

Billy nodded. ‘Aye.’

‘You remember Harry’s silk cravat? He wore a diamond pin in it an’ all.’

‘An’ his horse. Prime bit o’ flesh she were.’ Billy remembered every horse he’d ever seen. The best thing about being a highwayman would be having a grand horse. ‘That horse weren’t fast enough though,’ he added.

Both boys were silent for a moment.

Flash Harry had died on the gallows.

But it were worth it, thought Billy stubbornly. Flash Harry had near ten year o’ glory, throwing sovereigns down on the bar for a drink, buying ribbons and silk dresses for his light-o’-loves. Every boy at Higgins’s school envied Flash Harry when he swaggered in, in them high polished boots of his with the silver buckles, with a bag o’ gold watches to fence.

What was there else, for the likes of ‘im and Jem? Chimney sweeps died afore they was twenty, most like, the soot rotting their lungs an’ flesh. Get scurvy in the navy, or starve on a farmhand’s wage? Nay. You needed money to make money. At least if you was a highwayman you ‘ad a few grand years, with everyone lookin’ up to you, instead of a few bad ones.

Maybe, thought Billy, if Flash Harry’d had a better horse, he might be calling

stand and deliver

yet.

Holding up his pistols while trembling toffs tossed down their money bags…

‘I been thinking.’ Jem’s voice dropped to a whisper so Billy had to lean closer to hear. ‘You know what they says about this New South Wales?’

‘What?’

‘It’s fulla forests. Trees so thick the peelers can’t find no one if they runs away. There’s highwaymen there, too. Bushrangers, they calls ‘em.’

‘Who told you this?’

‘Shh. Keep yer voice down. Don’t want the ‘ole ship to hear. That sailor Tommy Two Tooth told me, last time the bucket came down, when I were ‘elping ‘im with the slops. Two Tooth says there’s country no white man’s ever seen. You can ride fer years and not see a soul. Mountains high as the sky, and only a dozen proper roads in the ‘ole colony.’

An empty country? Billy had known New South Wales were goin’ to be bad. If it weren’t bad, why send the convicts there? ‘So what?’

Jem’s elbow jabbed him in the ribs. ‘You daftie, don’t you see? England’s too small. Every tree in England has someone behind it waitin’ to inform to the peelers, but in New South Wales…why, they’d never find us. All we got to do is get ourselves a pair o’ horses. Just imagine, Billy boy. The two of us highwaymen at last.’

Billy did imagine it. A big black horse for him—white would stand out if they held up a coach at night. A brown horse for Jem—a quiet one, for Jem weren’t no good with horses. Not like Billy. Every horse in the street did what he asked it to, from the carter’s big draught mare to the poor brutes what

pulled the taxi cabs to fine ladies’ riding hacks. Master Higgins had said Billy could make a horse sit down and say its prayers. He’d even hired a horse from the stable, sometimes, and sent Billy to collect the loot from one o’ his customers who didn’t want to show his face in town. General, the horse’s name had been: a real high stepper, with a sweet mouth and—

‘I reckon we can do it,’ said Jem confidently. ‘Give us a few months to check out the lay o’ the land. Then we’ll escape together. Bushrangers in New South Wales. We’ve made it this far. Soon, Billy boy. We’ll be there soon.’

But it was another two days afore Billy felt the change that meant they’d sailed out of the open sea into a harbour. The ship bounced now, instead of plunging up and down the waves.

The last hours seemed longer than the whole nine months of the voyage. But even when he’d heard the yells of strangers on shore and the thud of rope as the ship was docked, still no one came to open the hatch.

Another day passed…or was it night? There was no way to tell down there in the darkness. Until the world exploded into light.

He put his hand up to shield his face. He had longed for the sun so long. He never guessed it could hurt like this.

He heard rather than saw a rope ladder drop down in the golden glare—the same one he’d climbed down all those months before.

‘Come on. Let’s get out of here.’ Jem felt his way from bunk to bunk.

Billy followed him, between the narrow bunks, staggering from weakness. All around him men were trying to steady themselves, groaning and swearing, waiting till they were used to the light.

Up the ladder he went, his hands almost too feeble to grasp the rungs. Up into that light so sharp it nearly cut his flesh, soft from so many months without the sun.

Then at last he was on the deck. His sight cleared enough to look around.

A dock, much like the one they’d left at Portsmouth, with wooden wharves and ships—two transport ships like theirs and a pair o’ whalers, with their big harpoons and barrels of whale oil, just like he’d seen back in Bristol. Even the shore looked much like home at first: barrels, carts and buildings of red brick and yellow stone. He could see houses—stone ones and ones made from slabs of wood—and yellow cliffs rising above the buildings, straggly shrubs climbing their flanks with determined roots, and windmills everywhere, the wide blades turning in the breeze.

But then he turned the other way and faced the harbour, and all thought of home vanished. This land was…different. Big, like Jem had said. Even the sky looked further away.

The harbour was vast, bigger than any Billy could have imagined, dwarfing the boats that bobbed on the waves: fishing boats and whalers and ferry boats, and a few canoes low to the water that must be natives fishin’. Green fingers of land jutted into the water, edged with black rocks. Most of the shore was lined with buildings, but behind them stretched trees, tall and blue-green.

‘That there’s what they calls bush,’ said Jem, holding up his arm so he could see despite the harbour’s glare. He grinned, showing his yellow teeth. Billy’s teeth were loose too after so long on water-stew. But at least none had fallen out on the voyage.

Billy blinked again in the harsh light. It wasn’t just that he’d been in darkness, he realised. It really was brighter here. The sky was so blue it looked like it was painted. No wisps of fog, not even any clouds.

The convicts were all out now, all who could stand. He wondered how many more were still lying in that stinkin’ hold, shivering in the water as they tried to find the strength to climb the ladder. Some dead maybe, unnoticed in the dark…

‘You! And you and you.’ A short man in pale trousers and shirt, with a bright pink cummerbund and a tall hat made out of some kind of dried leaves, poked the end of his whip at Jem and two of the others. ‘You follow me.’

Jem glared up at him. ‘Watcher mean?’

‘I mean yer comin’ with me, and no lip, that’s what.’

‘How about me friend? I ain’t goin nowhere without Billy.’

The man with the hat glanced down at Billy. ‘Don’t need no runts.’

‘Then you ain’t takin’ me.’

‘Ain’t I?’ The man laughed. ‘You got a choice. Walk free or come with a ball and chain.’ As he spoke two crew members grabbed hold of Jem’s shoulders and began to drag him to the gangplank.

They couldn’t take Jem! Billy stepped after them, trying not to stagger. ‘I’m strong enough,’ he yelled.

The man with the hat turned. He looked Billy up and down. ‘Three convicts are all I need today, and three is all I’m taking. Got here early to get the biggest.’

‘Taking where?’

The man looked at him with something approaching sympathy. Did he once stand on a deck like this? wondered Billy suddenly.

‘Ain’t no one told you what happens now? You gets assigned to whoever will feed you for as long as you’re sentenced.’

‘Not a gaol?’

‘No, lad. Not if yer lucky. New South Wales is a gaol without walls.’ He gestured to Jem and the other two. They were on the dock now, Jem still struggling weakly with his captors. ‘We’re goin’ to Dargue’s place, out Parramatta way. I’m Dargue’s foreman.’

‘Are you sure you can’t take me as well?’ asked Billy desperately.

The man hesitated. For a moment Billy thought he was going to agree. But the man shook his head. ‘I got me orders. You ain’t got a trade, have you?’

‘What’s a trade?’

‘Blacksmith? Groom?’

The only trade he had were pickpocket. Billy shook his head.

‘I’m sorry, lad. Maybe some other cove will pick you out.’ He bent his head and added softly, ‘You’re well out of it. Old Dargue’s heavy with the whip, and he don’t feed his workers none too good neither. You wait here till someone else picks you. I’m goin’ to seek a better place soon as I get me ticket of leave.’