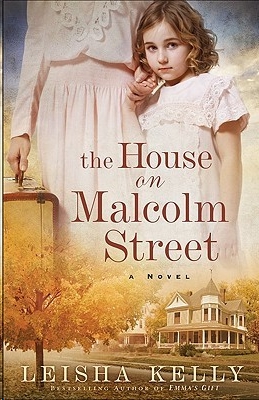

The House on Malcolm Street

Read The House on Malcolm Street Online

Authors: Leisha Kelly

Tags: #Fiction, #Christian, #Historical, #General, #Religious, #ebook, #book

Books by Leisha Kelly

Julia’s Hope

Emma’s Gift

Katie’s Dream

Till Morning Is Nigh

C

OUNTRY

R

OAD

C

HRONICLES

Rorey’s Secret

Rachel’s Prayer

Sarah’s Promise

the

H

ouse

on

M

alcolm

S

treet

A N

OVEL

LEISHA KELLY

© 2010 by Leisha Kelly

Published by Revell

a division of Baker Publishing Group

P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287

www.revellbooks.com

E-book edition created 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – for example, electronic, photocopy, recording – without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

ISBN 978-1-4412-1387-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

To my wonderful family

with love always

Contents

September 1920

I plopped Mother’s old carpetbag next to the railing and grabbed for Eliza’s thin glove. “Don’t step too close, please. The train is almost here.”

“I won’t, Mommy,” little Eliza promised, her rounded cheeks flushed pink with excitement. “I just want to see.”

Our other bag, still slung over my shoulder, was weighting me terribly, and I tried to shift it. Here we were on the wide oak platform, though I would have preferred to run the other way and never come near this or any other train station. My feet hurt, I’d grown hot despite the coolness of the day, and though I’d tried to fix my hair as best I could out-of-doors this morning, such a long walk in the breeze surely had it looking disheveled again. I would have liked to be almost anywhere else, at least to have some other option. But despite all my fretful efforts, I could think of none.

Six-year-old Eliza, whom I sometimes called Ellie, was just as eager in this new experience as I was wary. Her rag doll dangled limply in her free hand as she strained forward in an effort to see the approaching locomotive through the press of the crowd gathering around us.

“How big is it, Mommy? Is it really, really big?”

“Yes. Terribly. You’ll see soon enough.”

The train whistle blared, painful and shrill, piercing right through me. Clouds of steam and dust rolled toward the platform, and my heart fluttered violently in my throat. As the locomotive roared to a stop, I tightened my grip on my daughter’s hand but then clutched as well at the iron rail to squelch the urge to snatch her up and flee. Little Eliza would not have been so thrilled with the prospect of a train ride, nor even with the sight of the awful thing, if she knew everything that I knew about trains.

“Mommy, Mommy! Can’t we go closer?”

“No! We must wait till it is stopped completely!”

The huge black locomotive slid nearer, churning out plumes of smoke, steam, and choking dust. For a moment it seemed to be coming straight for me, and I could scarcely breathe. The whine of the great wheels grinding to a halt jarred me to the core of my being. It was utter foolishness to come to this train station, even for the hope of a fresh start. How could I go through with it?

“When can we get on?” Eliza persisted.

I froze, trying to regain composure. My grip on the rail was painful now but my knees were so weak and my head so unsteady I was afraid to loosen it.

How had John felt when he’d stood here on this platform? I could hardly think of him without tears filling my eyes, but in this place it was even harder.

Why did it have to happen? We’d had so little time together!

“Mommy, don’t squeeze me so tight.” Eliza squirmed uncomfortably.

“I’m sorry.” I relaxed my grip, took a deep breath.

John would always do what he had to do. No matter how hard it was. He would never let fear stand in his way. Especially foolish, irrational fear like mine.

Eliza stared up at me. “Are we really going to ride?”

I nodded, mustering all the courage I could. “Yes. We are going to Aunt Marigold’s in Illinois.”

“Marigold is a lovely name,” she mused.

I sighed. My dear daughter had always been quick with bright and cheerful observations. I could only hope Marigold McSweeney’s disposition matched Ellie’s enthusiasm.

All the women in my husband’s family had been named for flowers, including his long-deceased mother, Azalea. There was a Daisy. Petunia. Violet. Even Zinnia. That John and I had given our little girl “Rose” for a middle name might not be good enough among such folk. Marigold had written a letter recommending the name “Peony” before Eliza was even born.

I had no idea what to expect at Marigold’s, but we couldn’t stay here in St. Louis. After John’s death I’d tried to find work, but it was next to impossible with no one to care for my children. And then the influenza that had killed so many in 1918 and 1919 took another dreadful sweep through our neighborhood. I became gravely ill, and late in January little Johnny James had died. If I’d not had Eliza, I would have wanted to die too.

The landlord had been patient for a while, but we lost our home when a businessman offered him more for it than he was willing to turn down. I’d already been selling our furniture and household items for the money to live on. We barely had anything left. Not enough to find another home on our own, not even for the first thirty days. Aunt Marigold did not know all of that. And yet she’d invited us months ago to the large home where she took in boarders. She’d offered to let us stay until we could get a fresh start. It had seemed like such a strange proposition when I first got the letter last winter. I’d never met Marigold face-to-face, had never been any farther into Illinois than Alton. But now, what option did we have? I couldn’t move in with my father. I absolutely could not put Ellie or myself through that, ever.

The station platform grew more crowded now that the train had stopped. Where had all these people come from? I knelt beside Ellie and drew her close, just to be sure of her in the press. City crowds still made me nervous, despite my years in St. Louis. If there was one thing positive about having to start over in Illinois, it was that I’d be in a small town again, no bigger than the one nearest the farm where I grew up.

“Are all of these people going to ride the train with us?” Eliza asked.

“No. Some are surely here to greet people just arriving, or to say good-bye to their loved ones going away.”

She looked around uncertainly. “Did anyone come to tell us good-bye?”

“No.” There was nothing else to tell her. Who would come? We’d already said good-bye to Anna Butler, our former neighbor, days ago. Father didn’t know we were leaving, and we had no other family.

We watched and waited as people began to exit the train. I had already been told that this train would not linger long. Soon there was a general press toward it and then a shouted announcement for passengers traveling east.

I picked up the carpetbag that along with my heavy shoulder bag held what little remained of our belongings.

We’re destitute. Relying on the mercies of John’s relative. Where is God in all of this? Where was he when we needed him so badly?

Maybe a couple of deep breaths would help calm my nerves. It would be wrong to cry in front of these strangers, and especially in front of my daughter right now. Somehow I needed to find a way to be strong and not look afraid. “Come on,” I told Eliza as cheerfully as I could. “They’re beginning to board.”

It was not easy to step so near what I’d always thought of as a horrid, belching, man-eating monster. I’d heard people speak of their admiration and even gratitude for trains. But to me, from my earliest days, they’d been quite literally the stuff of nightmares, to be avoided as much as possible.

My hands shook ever so slightly, and I fought with all the strength I could muster against the threat of tears as I led Eliza through a swirl of leaves to the line where a conductor had begun calling passengers to board. I could not let myself be stopped. If we did not leave St. Louis for Marigold’s boardinghouse, if we did not get on this train, where would we spend another night? In the park again, among the birds and beasts, and who knew what else, wandering the city after dark? I could not do that to my daughter. Nights would be so much colder soon. I had to find a way for her, even if it was with a strange woman in an unfamiliar town.

Eliza bounced up and down as though we were in line for a carnival ride. She was a boisterous little girl, despite our sorrows less than a year ago. I couldn’t help thinking of her father and his death on a day not unlike this one, clear and beautiful with a flurry of dancing leaves. It had been a freakish accident, the result of his short train ride to Florissant to investigate a job opportunity. And as soon as I knew something had happened, I’d prayed. I’d begged God for John to come home to us safe and sound as always. But my prayers had been useless. John had died needlessly, because trains and train tracks were horrid, unpredictable places where metal and steam rule like tyrants over human life.

My heart thundered as this train blew its whistle again, as if taunting me. I tried to lay such thoughts aside when it came our turn to board. But I still found myself shaking as we climbed the metal step and moved to find a seat in the narrow railcar.

“Mommy,” Ellie begged. “I want to be by the window so I can look out the whole way!”

“Just sit down wherever you find a place and hold on,” I whispered. She looked at me and dropped to a passenger chair in an empty row but then slid over until she could look out easily.

We didn’t start moving. Not yet. I sat beside her, stiff and uncomfortable, wishing the ride would start so it could just be over. A ghastly scene flashed into my mind of blood, a mangled leg. Trains were killers, pure and simple. How could I possibly endure riding miles in the belly of one with such memories assaulting me?

It’s just too soon. That’s the problem. Ten months is not enough time to feel normal again after losing my precious husband. And then our only son.

I sniffed, at the same time arranging our bags near my feet and hoping Eliza did not notice the trouble I was having. I could not imagine being happy about a train ride when I was six. At that age, giant locomotives had pursued me in my dreams, and even in my waking hours the sound of their whistle had given me chills.

But I was grown now. Despite the circumstances of John’s death, it was time to block such things out of my mind. I opened one of our bags and pulled out a comb to fix my hair and Eliza’s. Hopefully, we wouldn’t arrive at Aunt Marigold’s looking like vagabonds.