The I Ching or Book of Changes (139 page)

7

. [Yao, Shun, and Yü are the three rulers held up as models by Confucius.]

8

. [Chêng Hsüan, A.D. 127–200.]

1

. [First Wing, Second Wing.]

1

. [See

here

for numerical values.]

1

. [These characterizations are given again with the respective hexagrams in

bk. III

, under the heading “Appended Judgments.”]

1

. [About the middle of the twelfth century B.C., according to traditional chronology.]

1

. [See

here

.]

1

. [206 B.C.–A.D. 220.]

2

. [See

here

.]

3

. [Here and on the pages following, there are occasional discrepancies in regard to the examples cited.]

4

. [See

bk. III

.]

1

. [For explanation, see

here

.]

2

. [

Tsa Kua

: Tenth Wing. See

here

.]

3

. [

T’uan Chuan

: First Wing, Second Wing. “Decision” is the equivalent of “Judgment.”]

4

. [See

here

, where this passage is quoted. Here, as in a number of other instances, the phrasing differs somewhat from one book to another.]

5

. [

Hsiang Chuan

: Third Wing, Fourth Wing. In

bk. I

, under the heading “The Image,” the reader has become familiar with the portion of this commentary known as the Great Images. It is repeated in

bk. III

under the same heading. The rest of the commentary, which explains the line judgments—though called Small Images (see

here

)—appears in the passages designated

b

under the heading “The Lines.” The passages designated

a

repeat the line judgments of

bk. I

. The German edition omits this repetition in the treatment of the first two hexagrams. However, the presence of the line itself makes the commentary so much more intelligible that it has seemed desirable here to supply the omission. Under “Six in the third place” in K’un, a parenthetic completion of the line text under

b

, and a sentence in the comment explaining this interpolation—both supplied by Wilhelm for elucidation in the absence of

a

—have been omitted as superfluous.]

6

. [

Wên Yen

: Seventh Wing.]

7

. [In the German rendering, these correlations are stated in four sentences so printed that they appear as a passage from the

Wên Yen

. Actually they do not occur in the

Wên Yen

. It is to be assumed therefore that they are part of Wilhelm’s comment on

a

1.]

8

. [See

here

–

here

.]

1

. [The Commentary on the Decision makes two sentences of the one. “The last words” refers to the last statement in the preceding paragraph of the Commentary on the Decision, and “what follows” refers to the first sentence of the next paragraph.]

2

. Another reading of this line is:

When there is hoarfrost underfoot,

The dark [power] begins to grow rigid.

If this continues,

Solid ice results.

3

. In the text of the commentary, the six in the second place is explicitly named as ruler of the hexagram. [The reference here is not to the Commentary on the Decision but to another commentary not presented in Wilhelm’s translation.]

4

. [See

here

, n. 5.]

5

. [The nature of yin and yang.]

6

. [The twelfth month in our calendar. See

here

, n. 1.]

1

. [

Hsü Kua:

Ninth Wing. There is no text of this wing for the first two hexagrams.]

1

. [Symbolized by the outer trigram.]

1

. In the text, the character for “leads” is written

tu

; which means “to poison,” but should be read

tan

, “to lead.”

2

. The word

lü

, “order,” in its original sense means a reedlike musical instrument. The literal meaning would be: “The army marches forth to the sound of horns. If the horns are not in tune, it is a bad sign.”

3

. The sentence

li chih yen

is best translated by taking the word

yen

(meaning “to speak,” “to explain”) simply as the equivalent of an exclamation point, which it frequently is in the Book of Odes. This yields the translation, “It furthers one to hold fast, to catch” (the game).

1

. [See

here

.]

2

. [See

here

.]

1

. [From

chap. VII

of the

Great Commentary

: Fifth Wing, Sixth Wing. See

here

–

here

for the sentences quoted.]

1

. [See

here

, sec. 5.]

1

. [No doubt “lowly” was meant here, since the first place is always strong. See

here

.]

1

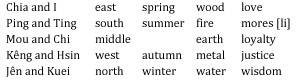

. The ten cyclic signs are:

1

. [The line is strong, but its place is weak.]

1

. Today one would speak here of the coming together of positive and negative electricity, the resultant discharge producing lightning.

2

. [Author of a treatise on the

I Ching

; died A.D. 1208.]

1

. [A.D. 226–249.]

2

. [A.D. 1623–1716.]

1

. In this hexagram there appear ideas that correspond with the mystical interpretations of the legends of Paradise and the fall of man.

1

. [See

here

.]

1

. [Literally, “clinging.”]

2

. [

Ti

means the earth]

1

. [Tui.]

2

. Literally, “Thus the superior man receives people by virtue of emptiness.”

1

. [See

here

.]

1

. [Li, the sun.]

1

. [Overthrown

ca

. 1150 B.C.]

1

. As these relationships indicate, the Chinese family is the patriarchal clan, which forms the nucleus of the patriarchal state. This trend of thought is developed still further in the Great Learning [

Ta Hsüeh

].

1

. Cf. the arrows of Helios.

1

. According to another interpretation, the big toe from which one is to liberate oneself is the six at the beginning; with this line there is a relationship of correspondence from which one must free oneself.

1

. [A dictionary compiled

ca

. A.D. 100.]

1

. [The Chinese text reads literally, “The place is not correct.” Wilhelm’s translation follows suggestions of the Chinese commentators.]

1

. [See

here

, where this line includes the augury, “No blame.”]

1

. Since the image is based on the idea of the drawing up of water, the meaning of the individual lines grows the more favorable, the higher the line stands.

1

. [T’ang the Completer (see

here

); Wu Wang, son of King Wên.]

2

. [Wu=Mou. See

here

for a discussion of the cyclic signs.]

3

. [Mou and Chi do not appear in the diagram showing the cyclic signs in relation to the trigrams in the Inner-World Arrangement (see

here

), since this pair of cyclic signs stands for the center, not for one of the cardinal points. K’un is connected with Mou and Chi: since it too symbolizes the center, The cyclic signs and the primary trigrams represent two different systems of speculation, the one base on the “five stages of change,” the other on the dualism of yin an yang. Therefore the two systems cannot coincide point for point.]

1

. [See

here

, n. 1.]

2

. The

ting

of ancient China had either three legs or four. Since the divided line at the beginning touches the earth as it were at only two points, it suggests the idea of a

ting

upturned.

Other books

Brooke's Wish by Sandra Bunino

Captain Wentworth's Diary by Amanda Grange

Vintage PKD by Philip K. Dick

Facing Justice by Nick Oldham

My Hollywood by Mona Simpson

Drake the Dandy by Katy Newton Naas

All's Fair in Love and Lion by Bethany Averie

Last Act of All by Aline Templeton

Mayday at Two Thousand Five Hundred by Frank Peretti

Drinks Before Dinner by E. L. Doctorow