The I Ching or Book of Changes (71 page)

CHAPTER XI. The Value of Caution as a Teaching of the Book of Changes

The time at which the Changes came to the fore was that in which the house of Yin came to an end and the way of the house of Chou was rising, that is, the time when King Wên and the tyrant Chou Hsin were pitted against each other.

1

This is why the judgments of the book so

frequently warn against danger. He who is conscious of danger creates peace for himself; he who takes things lightly creates his own downfall. The tao of this book is great. It omits none of the hundred things. It is concerned about beginning and end, and it is encompassed in the words “without blame.” This is the tao of the Changes.

King Wên, the founder of the Chou dynasty, was held captive by the last ruler of the Yin dynasty, the tyrant Chou Hsin. He is said to have composed the judgments on the different hexagrams during his captivity. Because of the danger of his situation, all these judgments emanate from a caution that is intent on remaining without blame and thus attains success.

CHAPTER XII. Summary

1. The Creative is the strongest of all things in the world. The expression of its nature is invariably the easy, in order thus to master the dangerous. The Receptive is the most devoted of all things in the world. The expression of its nature is invariably simple, in order thus to master the obstructive.

The two cardinal principles of the Book of Changes, the Creative and the Receptive, are here once more presented in their essential features. The Creative is represented as strength, to which everything is easy, but which remains conscious of the danger involved in working from above downward, and thus masters the danger. The Receptive is represented as devotion, which therefore acts simply, but which is conscious of the obstructions inherent in working from below upward, and hence masters these obstructions.

2. To be able to preserve joyousness of heart and yet to be concerned in thought: in this way we can determine good fortune and misfortune on earth, and bring to perfection everything on earth.

In the text there appear next to the expression, “to be concerned in thought,” two other characters that Chu Hsi has quite correctly eliminated as later additions. Joyousness of heart is the way of the Creative. To be concerned in thought is the way of the Receptive. Through joyousness one gains an overall view of good fortune and misfortune, through concern one attains the possibility of perfection.

3. Therefore: The changes and transformations refer to action. Beneficent deeds have good auguries. Hence the images help us to know the things, and the oracle helps us to know the future.

The changes refer to action. Hence the images of the Book of Changes are of such sort that one can act in accordance with the changes and know reality (cf. also

chapter II

above, where inventions are traced to the images). Events tend toward good fortune or misfortune, which are expressed in omens. In that the Book of Changes interprets these omens, the future becomes clear.

4. Heaven and earth determine the places. The holy sages fulfill the possibilities of the places. Through the thoughts of men and the thoughts of spirits, the people are enabled to participate in these possibilities.

Heaven and earth determine the places and thereby the possibilities. The sages make these possibilities into reality, and through the collaboration of the thoughts of spirits and of men in the Book of Changes, it becomes possible to extend the blessings of culture to the people as well.

5. The eight trigrams point the way by means of their images; the words accompanying the lines, and the decisions, speak according to the circumstances. In that the firm and the yielding are interspersed, good fortune and misfortune can be discerned.

6. Changes and movements are judged according to the furtherance (that they bring). Good fortune and

misfortune change according to the conditions. Therefore: Love and hate combat each other, and good fortune and misfortune result therefrom. The far and the near injure each other, and remorse and humiliation result therefrom. The true and the false influence each other, and advantage and injury result therefrom. In all the situations of the Book of Changes it is thus: When closely related things do not harmonize, misfortune is the result: this gives rise to injury, remorse, and humiliation.

The close relationships between the lines are those of correspondence and of holding together.

1

According to whether the lines attract or repel one another, good fortune or misfortune ensues, in all the gradations possible in each case.

7. The words of a man who plans revolt are confused. The words of a man who entertains doubt in his inmost heart are ramified. The words of men of good fortune are few. Excited men use many words. Slanderers of good men are roundabout in their words. The words of a man who has lost his standpoint are twisted.

This passage summarizes the effects of states of mind on verbal expression. It becomes plain therefrom that the authors of the Book of Changes, who are so sparing of words, belong in the category of men of good fortune.

The Structure of the Hexagrams

1.

G

ENERAL

C

ONSIDERATIONS

The foregoing supplies most of what is necessary for an understanding of the hexagrams. Here, however, there follows a summary regarding their structure. This will enable the reader to perceive why the hexagrams have precisely the meanings given them, why the lines have the often seemingly fantastic text that is appended to them—indicating, by means of allegory, what position the line holds in the total situation of the hexagram, and to what degree it therefore signifies good fortune or misfortune.

This substructure of explanation has been carried to great lengths by the Chinese commentators. Since the Han period

1

especially, when the magic of the “five stages of change” became associated with the Book of Changes, more and more mystery and finally more and more hocus-pocus have become attached to the book. This is what has given the book its reputation for profundity and unintelligibility. I believe that the reader may be spared all this overgrowth, and have presented only such matter from the text and the oldest commentaries as proves itself relevant.

Obviously in a work like the Book of Changes there is always a nonrational residuum. Why, in a particular instance, one given aspect is stressed, rather than some other that might just as well have been, can no more be accounted for than the fact that oxen have horns and not upper front teeth as horses have. It is possible only to give proof of the interrelations within the framework of what is posited; to sustain the analogy, it is like explaining to what extent there is an organic connection between the development of horns and the absence of upper front teeth.

2.

T

HE

E

IGHT

T

RIGRAMS AND

T

HEIR

A

PPLICATION

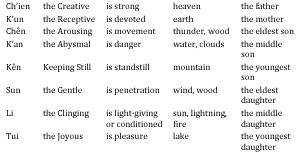

As has previously been pointed out, the hexagrams should be thought of not merely as made up of six individual lines but always as composed of two primary trigrams. In the interpretation of the hexagrams, these primary trigrams play a part according to the various aspects of their character—first according to their attributes, then according to their images, and finally according to their positions within the family sequence (here uniformly only the Sequence of Later Heaven

2

is taken into account):

These general meanings, particularly when it is a question of interpretation of the individual lines, must be supplemented by the lists of symbols and attributes—at first glance seemingly superfluous—given in

chapter III

of the

Shuo Kua

, Discussion of the Trigrams.

In addition, the positions of the trigrams in relation to each other must be taken into account. The lower trigram is below, within, and behind; the upper trigram is above, without, and in front. The lines stressed in the upper trigram are always characterized as “going”; those stressed in the lower trigram, as “coming.”

From these characterizations of the trigrams—already in use in the Commentary on the Decision—there was later constructed a system of transforming the hexagrams one into

another, which has led to much confusion. This system is here left wholly out of account, since it is not in any way essential to the explanation. Nor has any use been made of the “hidden” hexagrams—i.e., the idea that basically each hexagram has its opposite hidden within it (for example, within Ch’ien is K’un, within Chên is Sun, etc.).

But it is decidedly necessary to make use of the so-called nuclear trigrams,

hu kua

. These form the four middle lines of each hexagram, and overlap each other so that the middle line of the one falls within the other. An example or two will make this clear:

The hexagram Li, THE CLINGING, FIRE (

30

), shows a nuclear trigram complex consisting of the four lines:

The two nuclear trigrams are Tui, the Joyous, as the upper ( ), and Sun, the Gentle, as the lower (

), and Sun, the Gentle, as the lower ( ).

).