Read The Ian Fleming Miscellany Online

Authors: Andrew Cook

The Ian Fleming Miscellany (13 page)

When it came to delivering a plot line, a little like Agatha Christie, Fleming experimented with the method of telling a story. In the

Spy Who Loved Me

, written in 1961, for example, he made a dramatic departure and told the story in the first person through a Canadian girl by the name of Vivienne Michel. In an even riskier move, Bond does not come into the story until two thirds of the way through the book. While it was in many ways a brave and bold approach, it was not one that was well received by the critics. Charles Stainsby of the weekly magazine

Today

described it as âone of the worst, most boring, badly constructed novels we have read'.

This was not the first occasion on which he had encountered bad or critical reviews relating to his plots. Having had a relatively good stretch between 1953 and 1958,

Dr. No

, published in March of that year, was accused by some critics of being a re-working of British author Sax Rohmer's

Fu Manchu

. Paul Johnson, writing in the

New Statesman

, went somewhat further by describing the book as the nastiest he had ever read. âMr Fleming', he wrote, âhas no literary skill; the construction of the book is chaotic, and entire incidents and situations are inserted and then forgotten in a haphazard way.' To Fleming, however, the secret of writing a best seller was not to be found in the intricacies or otherwise of the plot, it was all down to the author's ability to incentivise the reader to turn over the pages. The success of his story telling was all about how you did it rather than what you did. Nothing, in his view, should interfere with the essential dynamic of the thriller. Prose should ideally be simple and unmannered and should not linger too long over descriptive passages. Having said that, he was equally of the view that these rules were occasionally there to be broken. Looking back on the writing of

Goldfinger

in 1958, he confessed to indulging the reader with large doses of what he considered they should be interested in and proceeded to take up some three chapters in describing in fine, blow-by-blow detail, the round of golf between Goldfinger and Bond. He was equally equivocal that there should be no complications in names, relationships, journeys or geographical settings that would likely confuse or annoy the reader. Unlike Christie plots, he believed there must never be what he felt were indulgent recaps where the central character theorises in his mind on a list of suspects or reflects on what he might have done or what he proposes to do next.

Gustav Steinhauer, Melville's German intelligence opposite number and author of the Bank of England Plot, considered by many to be âthe Real Goldfinger'.

National Archive

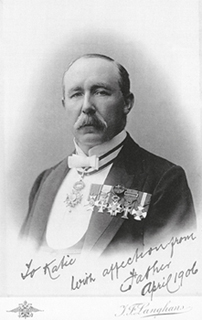

William Melville, the Secret Service Bureau Chief who smashed the plot to blow up the Bank of England's gold reserve in 1914.

Author's collection

Fleming's modus operandi was to crack on at break-neck speed, hustling the reader quickly beyond what he often referred to as the âdanger points of mockery'. This approach was equally a reflection of his writing technique which embodied the principle of never correcting anything and never looking back at what he had written until he had finished.

At a time when few post-war Britons were willing or able to venture beyond their native shores on a foreign holiday, Fleming's books were the perfect antidote. His backdrops were always sunny, exciting and luxurious locations. At the same time, his narrative frequently employed the use of familiar names and objects: a Ronson lighter, a 4½-litre Bentley with an Amherst-Villiers super-charger and the Ritz Hotel in London are all points of familiarity that punctuate the reader's journey to fantastic adventure.

Ultimately, Ian's real ambition was not to be recognised as a great writer or to write great books but to see his creation James Bond make the transition to the big screen and find the success that that authors like Leslie Charteris had done. As he acknowledged himself in 1962, there was not much money to be made from book royalties and translation rights; it was selling the film rights that made it all worthwhile financially. In this sense, it is significant that when, in 1962, after some eight years of trying, he finally succeeded in obtaining a film deal with Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, the film producers found very few of his literary plots of use or value in terms of constructing scripts. Of all the Bond books he wrote, few were to make the transition from book to screen in terms of the plot.

HE

C

OVERS

â¢

Fleming had done a good job as a cover designer with some of his earlier books, but when it came to

From Russia with Love

he found the best artist yet. Richard Chopping was 40 and established as a painter of exquisite flowers, plants and insects. After an exhibition of his in 1957, he and his partner Denis Wirth-Miller gave a dinner party. Francis Bacon brought Anne Fleming. Soon afterwards they and Bacon were invited to dine with the Flemings in their house in Victoria Square, a quiet enclave off the Buckingham Palace Road. Fleming, presumably having heard about Chopping's work from Anne, asked him to paint a picture he could use as the cover for his next book. (According to Chopping himself later, he was the second choice, although the first would have produced the goods even more slowly.) Money wasn't mentioned. Ian was unfairly self-deprecating about the books themselves (âYou don't want to read them. They're rubbish.') For

From Russia with Love

, they agreed on a still life with gun, which Fleming would provide, and thorny rose, on a pale wood-grain background.

Chopping painted this but delivered it somewhat late, at Fleming's office in Gray's Inn Road. Fleming grinned as he entered; he was on the phone to somebody. âYou can ask him yourself,' he laughed, âhe's just walked through the door.' Chopping found himself talking to Scotland Yard. Three people had met a sudden end from the barrel of a Smith and Wesson revolver. The only licensed Smith and Wesson revolver, in the area they were searching, was the pistol Ian had given him to paint. Ian had borrowed it from a reputable gun dealer. The prime suspect, until forensics fortunately established that this gun hadn't been fired, was either Chopping, Fleming or the dealer.

Ian loved the picture. The usual rate for a book jacket was ten guineas (£10.50) but Chopping asked £30. Ian insisted he was worth £40. Chopping did a few more covers after that, and then in 1961, he began to supplement his income with a lecturing job at the Royal College of Art. He wanted to reserve his spare time for his own work. He was bored by James Bond by then anyway, and refused a fourth commission. However, Fleming âinsisted, saying “your covers sell the books” although this had previously been hotly denied when I sought to raise my price'.

So Chopping asked for copyright, as well as much more money, and that was agreed. He then asked for royalties and was refused. So he simply put the price up with each successive job, until finally â having been paid £365 for one of them â he was publicised as âthe highest paid book jacket designer in the world'.

LOVE AND MARRIAGE

![]()

ARRIAGE

â¢

Ian Fleming was unsuited to marriage. He was too moody, too selfish and too easily bored. The liaison with Anne, which began in the 1930s, had endured for a remarkably long time partly because they both had other relationships and other interests to pursue. They did not have to share the same roof for months on end. Sometimes they had to communicate by letter or not at all. They both delighted in sado-masochistic sex, which kept the candle burning, but inventiveness would eventually run out there too.

Once they were married they did their best to avoid passion-killing domesticity. Ian wanted to remain fit and attractive. When Barbara Skelton saw him in 1954 she noticed he no longer was; these days he had a complexion like raw beef and a big behind. Yet Ian's view, according to Bryce, was that a healthy man in his forties should be made of âvelvet stretched on bone' or turn into a middle-aged slob. Aware of increasing flab, he and Ivar agreed that they would both lose it under medical supervision within six months. Each bet the other $10,000 that he couldn't do it. If they both failed, the $20,000 would go to charity. They both succeeded. Later on, Ian did âa champagne cure for chronic alcoholism which I find is very beneficial and my smoking has been vastly reduced, so I hope that before long a new Fleming will arise from the ashes of the old'.

He never felt good enough, or excited enough, for very long. Marriage had motivated him to stick to a routine for a purpose, but it didn't offer a thrilling life.

He was pleased to have a son, but not particularly interested. Film, TV and serial rights in the Bond books were put in trust for Caspar, but hands-on parenthood offered few delights to either Ian or Anne. Nanny Sillick looked after little Caspar at No. 16 Victoria Square and at their house in St Margaret's Bay, on the Kent coast. Permanent domestic staff were also in residence in London, which â since both Caspar's parents were often away â made him the baby boss of his own household. He had been born to parents aged 43 and 38, whose own parents would have expected the children to be âbrought down' for an hour in the early evening, and otherwise kept out of sight. So it was for Caspar in the 1950s. Nanny Sillick did the nappy changing and playing with wood bricks, the maid did the laundry, the cook mashed the baby food. After a while the Flemings decided that Nanny Sillick might as well keep Caspar down in Kent all the time, and they would visit at weekends and at Christmas. Christmas at St Margaret's Bay involved quite a lot of entertaining, so they rented the house next door for a cook. Given James Bond's fussiness over drinks and cigarettes, guests might have expected superb cuisine. Barbara Skelton, who was a good cook, found their food dreary in the extreme. When she was still married, just about, to Cyril Connolly, Connolly called her after a meal at the Flemings'.

â“What did you have to eat?” I asked, knowing the form.

“Unripe avocados and some rather dull little soles.”'

Avocados were barely known then, and only Harrods or Fortnums would stock them. Anne and Ian knew the kind of thing they should eat to look smart, but Ian at least was a steak-and-chips sort of person.

Ian's health was an ongoing concern. By the time he was 50, in 1958, he was in terrible shape. He was often drunk. He had a bad back, dodgy kidneys, a dicky heart and stress. He smoked as much as ever. When he was in Jamaica that year he kept asking Anne, by letter, to find them a house where they could settle down. He wanted a place, he said, where he could afford the heating bills. (The soul of Granny K lived on.) Anne's solution was a forty-roomed wreck in Dorset, with dry rot and a ballroom. They bought it, and it kept her conveniently occupied for the next four years. Dredging the lake cost quite a lot. When it was finished he decided to take a flat of his own at Sandwich, to be nearer the golf course.

Holidays, at least, were chosen by Ian, for Ian. In a repeat of the Esmond-Anne-Ian trip to Cornwall, he was hoping somehow to re-live happier, more innocent times. He loved fast cars and had enjoyed Kitzbühel thirty years ago, so in mid-1950s he drove Anne and Caspar to Austria in his Thunderbird in summer. There was a golf club, so he played golf. Anne painted. Presumably Nanny Sillick spent her days with the little boy. When Caspar was 7 or 8, he had a governess, who would accompany them on holiday and to Jamaica and give him the kind of attention that his parents were too self-absorbed to offer. At 10, in 1962, Caspar had a companion: his cousin Francis. Anne's sister, who like Eve Fleming's brothers was unable to manage life, died of drink that year, leaving Francis motherless. Anne more or less took him in as a companion for Caspar. It was probably too late. Anne herself was by that time addicted to barbiturates, which Caspar started taking occasionally when he was 11.