The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (27 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Edmonia did not elaborate to Anne on her new Catholic friends. With patrons like Lord Bute, the fund-raisings in America, and her new market, she had put financial problems behind her.

After nearly four years in Europe, Edmonia must have forgotten how routinely Americans bullied people of color. She found reminders soon enough. A Cleveland hotel asked her to take her meals in her room rather than in its public restaurant where other guests “might find fault.”

[395]

She would soon appreciate that she got a room at all. In Syracuse, the hotels forced her to wander dark streets in search of shelter.

[396]

She finally found a clergyman willing to take her in. In other cities, her skin was insulted again.

The bigotry reopened old wounds, as it had in Florence, where she penned angry letters, and at her studio in Rome, where she used rude curses and gestures. She became so incensed during her first return to America that the press took notice. Newspapers as far as Texas reported on it.

She never let loose such complaints again, although observers noted more than one provocation. Our likely conclusion: Feedback from the stories must have horrified her. She chose her art and dignity over becoming famous for her rage. Angry protest was justified, but it was not part of her plan. She worked to appear friendly and serene, despite her natural temper, as she offered messages of pride and self-respect. She focused on her natural gifts. Obstacles based on race would not stop her from showing her art in America. She planned her travels with more care.

A word from Monsignor Silas Chatard,

[397]

who led the American College in Rome, could have prompted Lord Bute’s timely intervention. Msgr. Chatard would have been concerned with the papal interest in freed slaves and in helping colored American Catholics. His grandparents had fled the Haitian revolution. Raised in Baltimore, he knew about slaves, owners, and free colored people.

According to Edmonia, she and Msgr. Chatard were “well acquainted.”

[398]

He probably told her about the first American parish officially established for Negroes. The community of colored Catholics in Baltimore dated to the arrival of one thousand French-speaking refugees from Haiti. After seventy years of worshipping in quarters shared by a seminary, the chapel of a convent, etc., the congregation purchased its own building and dedicated it as St. Francis Xavier church in 1864.

She visited St. Francis Xavier where she offered a Madonna, asking only that the parish pay for the marble and its transportation to Baltimore. Its announcement book, Aug. 29, 1869, reads, “A first class artist, Miss Lewis, residing in the city of Rome, wishes to make a donation of a large marble statue to this church.”

Edmonia spent two weeks at the convent / orphanage as the church took up a special collection. The

Art-Journal

reported a few months later, “Miss Lewis … is also executing a Madonna for the Church of St. Francis in Baltimore by order of the archbishop.”

[399]

In 1871, Baltimore’s convent of the Oblate Sisters of Providence moved to Chase and Forrest Streets where they exhibited Edmonia’s

Virgin and Child

(now lost) in 1908. Assuming it is the same work promised to the St. Francis Xavier church, we quote the description carried in the

Baltimore Sun:

“Her skill in carving the statue, which stands on a pedestal in one of the rooms of the convent, is exquisite and shows a master hand. In the left arm of the Virgin is the infant Christ, and the right arm is pointing downward. It is said that the sculptor’s idea in having the arm pointing down was to show that the Virgin looks after the women of the world.”

Returning to Boston, she found its colored leaders had only admiration and praise for her. They offered no instructions, no injunctions, no caustic critiques. Expectations for her future ran high. The William Hathaway Forbes family hired her to make a portrait of their two-year old daughter, leaving us the charming anecdote we related earlier.

On a Tuesday evening, a festive reunion presented

Forever Free

to Rev. Grimes at Tremont Temple.

[400]

George Lewis Ruffin presided. After years of barbering, he had become the first colored American to graduate from Harvard Law School. Other speakers included Mr. Garrison, Rev. Waterston, Rev. Grimes, William Wells Brown, MD, author of

The Black Man

His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements

(1863), Mr.

William Craft, co-author of

Running a Thousand Miles to Freedom

(1860), and Mr. J. J. Smith, whose daughter Elizabeth became the first colored teacher in Boston’s mixed-race schools.

Forever Free

meant a great deal to all Americans for whom the fall of slavery was a life-affirming moment. Edmonia’s fans could not permit her to depart without taking her hand and thanking her. They presented her with a purse filled with money and a handsome mallet made of ivory – a symbol of “home,” as they called Africa – which reinforced Edmonia’s connection to them through her father. The enthusiasm washed away the challenges, the harsh criticism, and the cruel dismissals of Mrs. Child’s “sincere letter.”

Tremont Temple was the very place where she and Mrs. Child first met. Like the Sewalls, Mrs. Child now stayed away. Later she angrily condemned the statue’s realism and its admirers: “Good Elizabeth Peabody had written a flaming description of it for the Christian Register in which she said, ‘Every muscle is swelling with emotion.’ Now the fact is, her figure

had

no muscles to swell. The limbs were more like sausages.”

[401]

One of Child’s old friends accused her of deserting her mission, a charge she denied: “Miss Peabody rebuked me for what she called ‘my critical mood.’ She said, ‘as the work of a colored girl, it ought to be praised.’”

Child puffed herself to higher ground, claiming, “I replied, ‘I should praise really good work all the more gladly because it was done by a colored artist, but to my mind

Art

is sacred, as well as

Philanthropy,

and I do not think it either wise or kind to encourage a girl, merely because she is colored, to spoil good marble by making it into poor statues.”

Michelangelo himself could not have satisfied Child’s red-faced wrath. Edmonia’s religious coming out probably aggravated all the other irks. She had turned Catholic without warning, and in Rome no less. Child opposed religious intolerance. She clearly detested, however, the ancient hierarchy of the Church, its power, and its conflict with the representative institutions of America.

Irate enough to shake off shared goals, Child immolated their relationship and cut all ties. The historic bond forged at a celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation ended over a statue recalling the very moment of liberty.

Edmonia’s return visit to America was an overall triumph.

Forever Free

rested in the bosom of her people, debt free and safe. Her uncanny Longfellow strategy became part of her legend and a source of pride as she carved it in marble for Harvard. She had new commissions and she would also carve a bust of Rev. Grimes in expensive marble.

[402]

Her fame reached beyond newspapers. Summing up the progress of art the next year, a writer of popular history extolled expatriate talents of Ball, Powers, and Story. He added, “There is in Italy a young American coloured lady, Edmonia Lewis, whose talent in sculpture is already widely admired, and who has produced more than one proof of artistic genius.”

[403]

Back in Rome by December, Edmonia called on Anne Whitney directly.

[404]

She carried a book from Caroline Healey Dall of Boston, a women’s rights champion.

Although from a wealthy family, Miss Dall supported herself by lecturing, writing, and encouraging female pioneers. It seems she was also a fan of Edmonia’s.

Anne, no doubt, filled in Edmonia on the latest buzz of Rome – the outrages of Vinnie Ream – explained in the following chapter. Anne also took the occasion to visit Edmonia’s studio. She had not seen it for some time, perhaps since before Edmonia’s financial meltdown. What she saw prompted a full reversal of her earlier assessments. Writing to her sister, she remarked that Edmonia had improved and that her work was now superior to that of Vinnie Ream (now the object of Anne’s envy) and unnamed others

.

[405]

From Edmonia’s confident air, Anne sensed new commissions in America. Edmonia did let not her in on details. If she had, Anne would have hastened to tell. Anne’s sister, Sarah, instead, gave the news to her.

[406]

In our opinion, one was particularly important and from Boston.

As Boston’s first female physician, Dr. Harriot K. Hunt could identify with Edmonia’s struggles for recognition without confusing the issue with suffrage. Her successful practice forced the world to recognize her skill. Now seriously ill, she did not expect to live long. She commissioned a life-size marble statue of

Hygeia

(Figure 29), the daughter of the Greek god of medicine, for delivery by June 1872.

[407]

She wanted it to mark her grave. As she made her will, she assured that Edmonia would be paid.

After her return to Rome, Edmonia must have plunged into study of the Greek goddess of health. By April 1871, she was reportedly finishing the statue.

[408]

An interview two years later provided a unique account of its design, indicating the panels for its base represented both physician sisters (Sarah Augusta Hunt as well as Harriot).

[409]

Dr. Hunt died in 1875.

Hygeia

stands in the rolling hills of Mount Auburn Cemetery, final resting place of Boston’s most famous and wealthy.

[410]

There was no public unveiling ceremony or publicity. Possessing a distinctively feminine grace, it is one of Edmonia’s most unusual works. It was unrecognized by art historians for more than a century.

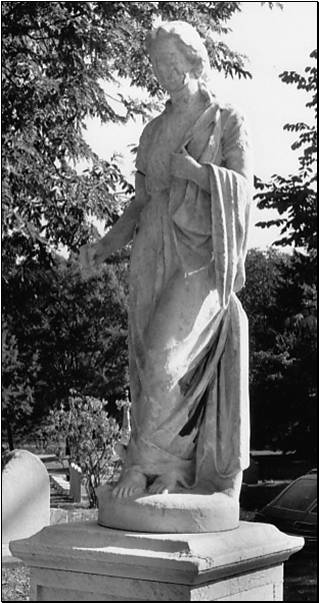

Figure 29.

Hygeia,

ca 1872

This graceful figure of

Hygeia,

goddess of health, marks the grave of Harriot K. Hunt in Mount Auburn Cemetery. Air pollution and winter freezes have taken their toll on the marble sculpture, 4 ft. 4 in. high on a marble base and a granite block. Her right hand once held a staff. Since this photo, the statue lost its right arm. Inscriptions now partly illegible read,

The Lord is Our Lawgiver,

and

Great Peace Have They Which Love Thy Law – The Sisters Physician, 1855.

Photo: Harry Henderson

.

Washington

While Edmonia was celebrating in Boston, a young sculptor of her generation arrived in Italy with her parents.

[411]

Like Edmonia, Vinnie Ream was naturally gifted and largely self-taught. Four years before, she had obtained permission from President Lincoln to model his bust in his White House office. She was nearly done when the assassin struck and her work became the art-sensation of Washington DC society.

Fate, grief, and her uncommon boldness made her famous at the tender age of seventeen. Her work was uniquely fresh, and an emotional Congress promptly entertained giving her a commission for a life-size memorial statue.

As an upstart bred on the frontier, she had more in common with Edmonia than with society sculptors such as Anne Whitney, Harriet Hosmer, and Emma Stebbins. Both she and Edmonia lacked tutors, formal anatomical studies, and years of apprenticeship. They both made art their sole source of income. They pressed beyond classical themes to portray modern times, shamelessly sold their medallions, and boldly sought social connections that could advance their careers. They were both driven to sculpt and first among their hobbies was music.

Writers Wreford and James matched them at once, the first in crisp support and the other with hollow scorn.

[412]

Another English writer called Vinnie a full-blooded Indian, citing her dark complexion and a costume that often included moccasins. Vinnie had romped with Winnebago children and wore Indian garb as a small child. She also took Indians as her subjects. Her brother hunted with the Cherokee and chose an Indian bride.

As women, they both met contempt in the male-oriented art world. Where Edmonia suffered because of the color of her skin, Vinnie bore a special cross of her own design. Many sculptors were bitter about how she enticed Congress to vote her $10,000 to memorialize the late President. Nearly all of them had dreamed of such a commission. Many had sketched

bozzetti.

(Many won sponsors. Thomas Ball’s memorial we described in the chapter on Florence. In Rome, Randolph Rogers was at work for the city of Philadelphia.

[413]

) Bedazzled by Vinnie’s bold charm and political connections, Congress had no interest in any of them.