The Italian Renaissance (34 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

How important the exact subject matter was to contemporary viewers is very difficult to say. Was a St Sebastian or a Venus chosen primarily for its own sake or as a pretext for representing a beautiful naked figure? How can a modern historian possibly answer such a question? It would certainly be a mistake to answer with confidence, but to avoid anachronistic interpretations we can at least investigate the ways in which paintings were described at the time. It is, for example, interesting to know that Titian called his mythological scenes ‘poems’ (

poesie

), even if we do not know exactly what he meant by the term – whether he was referring to the fact that he drew on Ovid’s poem the

Metamorphoses

or whether he intended to imply that he was following his own imagination rather than a text.

Some of the most intriguing literary evidence concerns what we call ‘landscape’ because it suggests an increasing awareness of the backgrounds of paintings, and even a shift towards considering these features

the true subject. Giovanni Tornabuoni asked Ghirlandaio in the 1480s, as we have seen, for ‘cities, mountains, hills, plains, rocks’ in a commission to paint stories from the life of the Virgin Mary. In the correspondence of Isabella d’Este and her husband Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, there are references to ‘views’ (

vedute

), and in one case to ‘a night’ (

una nocte

). The latter may have been a

Nativity

, but to describe a religious painting in this way would itself be significant. In 1521 an anonymous Venetian observer (often identified with the patrician Marcantonio Michiel) recorded the existence of ‘many little landscapes’ (

molte tavolette de paesi

) in the collection of cardinal Grimani.

10

Again, the humanist bishop Paolo Giovio described some of Dosso Dossi’s paintings, in the 1520s, as ‘oddments’ (

parerga

), consisting of ‘sharp crags, thick groves, dark shores or rivers, flourishing rural affairs, the busy and happy activities of farmers, the broadest expanses of the land and sea as well, fleets, markets, hunts and all that sort of spectacle’.

11

In other words, what we call ‘the rise of landscape’ in this period seems to correspond to changes in the way in which contemporaries looked at pictures.

12

What has been discussed so far is the more or less manifest content of Renaissance paintings. However, it is clear that some of them at least, like literary works, were intended to contain hidden meanings. How often this was the case, what the meanings were and how many contemporaries understood them are questions which require discussion, but they are rather more obscure.

It is advisable to begin this discussion with literature, where the hidden is sometimes at least made explicit in commentaries. Contemporaries were used to looking for hidden meanings in literature, if only because they were told from the pulpit that the Bible had four different interpretations, not only the literal but also the allegorical, the moral and the anagogical.

13

Some humanists looked for hidden meanings in worldly literature as well, even if they did not always distinguish the allegorical, the moral, and so on, as carefully as theologians did. In the fourteenth century, Petrarch, Boccaccio and Coluccio Salutati all interpreted classical myths as a ‘poetic theology’.

14

In the fifteenth century, Cristoforo Landino wrote that, when poetry ‘most appears to be narrating something most humble and ignoble or to be singing a little fable to delight idle ears, at that very time it is writing in a rather secret way the most

excellent things of all, which are drawn forth from the fountain of the gods.’

15

Commentaries expounded the hidden meanings (usually religious or philosophical) underlying the apparently secular or even frivolous surface of classical writers such as Virgil and Ovid or modern ones such as Petrarch and Ariosto.

Ovid is a useful example to discuss at this point, because his

Metamorphoses

inspired artists as well as poets of the Renaissance. From the twelfth century onwards, it became customary to ‘moralize’ him – in other words, to give the poem an allegorical interpretation. The allegorizations of Ovid by Giovanni da Bonsignore in the fourteenth century were printed in some Renaissance editions of the

Metamorphoses

, so that the reader could learn, for instance, that Daphne (who, fleeing from Apollo, turned into a laurel tree) stands for prudence while the laurel stands for virginity. The question how commonly these myths were given this kind of interpretation in the period remains problematic.

Ariosto was treated in a similar way by the all-purpose writer Lodovico Dolce, who produced an edition of

Orlando Furioso

in 1542 in which the flight of Angelica in the first canto is interpreted in terms of ‘the ingratitude of women’, while Ruggiero’s combat with Bradamante in the forty-fifth canto reveals ‘the qualities of a perfect knight’. These interpretations are described as ‘allegories’, but in modern terms they might be better described as symbols. Whereas Bonsignore treated Ovid’s characters as personifications of abstract qualities, Dolce simply generalizes about human nature from the actions of Angelica and Ruggiero.

One is left with the impression of a whole spectrum of hidden meanings, whether intended by authors or read into them by commentators – meanings which seem to have had considerable appeal to readers of the period. (Dolce, for example, would not have written anything if he had not thought it would sell.) This impression is worth bearing in mind when we turn to painting. Paintings of scenes from the Old Testament are likely to have been read by some people at least as the text was read, with an eye on what was to come – in other words, characters from the Old Testament were seen as ‘types’ or ‘figures’ of the New. Eve and Judith were both taken to prefigure the Virgin Mary. (Judith liberated Israel by cutting off the head of the Assyrian captain Holofernes; Mary liberated mankind by giving birth to Christ.)

New Testament scenes, by contrast, were painted for their own sake, but they may have been given a more subtle theological meaning on occasion, at least as an extra. At all events, it is interesting to find a friar, Pietro da Novellara, writing to Isabella d’Este about a sketch by Leonardo (Plate 7.1), offering the following theological interpretation, at least hypothetically (note the ‘may be’):

P

LATE

7.1 L

EONARDO DA

V

INCI

:

T

HE

V

IRGIN

, C

HILD AND

S

AINT ANNE

P

LATE

7.2 G

IORGIO

V

ASARI

:

P

ORTRAIT OF

L

ORENZO

DE’M

EDICI

A

cartoon of a child Christ, about a year old, almost jumping out of his mother’s arms to seize hold of a lamb. The mother is in the act of rising from St Anne’s lap, and holds back the child from the lamb, an innocent creature which is a symbol of the Passion [

significa la passion

], while St Anne, partly

rising from her seat, seems anxious to restrain her daughter, which may be a type of the Church [

forsi vole figurare la Chiesa

], who would not hinder the Passion of Christ.

16

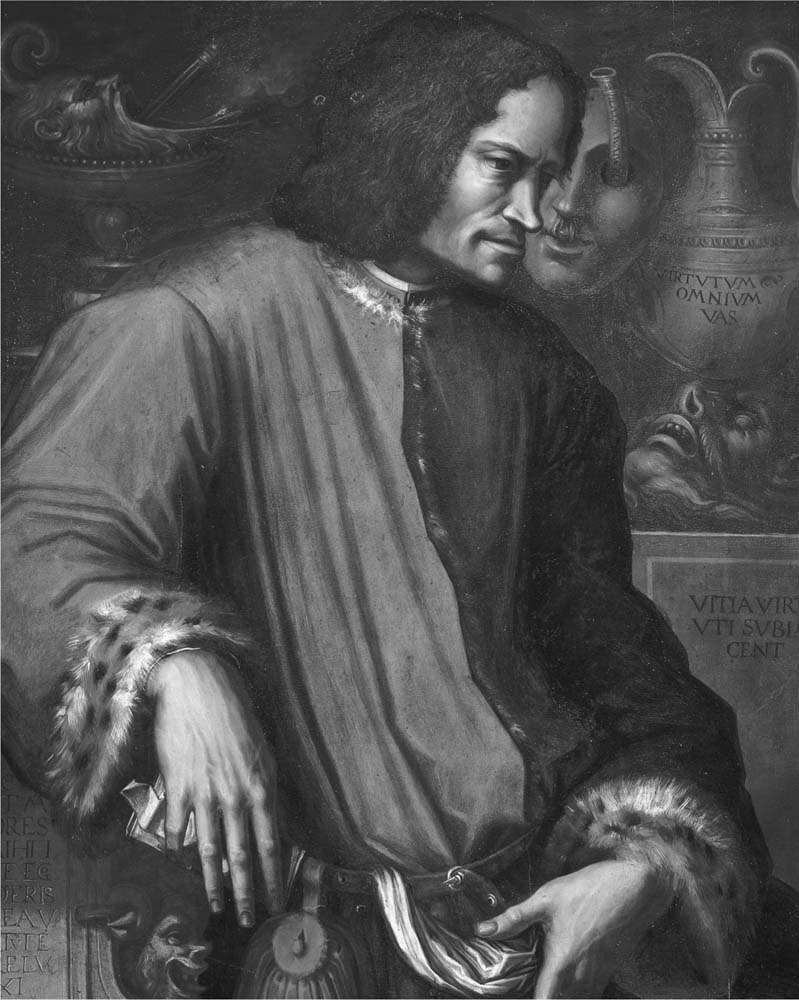

At this point it may finally be more or less safe to turn to the vexed question of the secular paintings of the Renaissance and their possible moral or allegorical meanings. At the end of the period, the evidence is sometimes extremely rich and precise – in the case of Vasari, for example, who explained his intentions in considerable detail. His portrait of the late Lorenzo de’Medici (Plate 7.2), he wrote, would depict in the background a vase, a lamp and other objects, ‘showing that the magnificent Lorenzo, by his remarkable method of government … enlightened his descendants, and this magnificent city’.

17

The programmes devised by sixteenth-century humanists such as Paolo Giovio, Vincenzo Borghini and Annibale Caro (above, pp. 116) are similarly detailed. More of a problem is posed by paintings of the fifteenth century, notably Botticelli’s, which have long been a subject of scholarly debate. His so-called

Primavera

, for example, illustrates a scene from another poem of Ovid’s, the

Fasti

, dealing with the nymph Flora and the month of May, but there is a good deal in the painting which the text does not explain. Humanists sometimes interpret the classical gods, as we have seen, as symbols of moral or physical qualities. Marsilio Ficino wrote on one occasion that ‘Mars stands for speed, Saturn for tardiness, Sol for God, Jupiter for the law, Mercury for reason, and Venus for humanity [

humanitas

].’ As he was writing to the youth who commissioned the

Primavera

, it has been suggested that ‘humanity’ is what Venus represents in the picture.

18

Again, Botticelli’s

Pallas and the Centaur

may be given a moral interpretation, with Pallas Athene (or, as the Romans called her, Minerva) standing for wisdom and the tamed centaur for the passions.

19

In most cases we can do no more than conjecture what the hidden moral meaning may have been. Contemporaries (apart from the artist, the client and their intimates) will have had a similar problem. The important point is to remember that many contemporaries approached paintings with expectations of meanings of this kind.

Hidden political meanings also figured on the contemporary ‘horizon of expectations’,

though they are even more difficult to decode, since topicality stales so rapidly. Could Botticelli’s Pallas, for example, whose gown is adorned with the Medici device of interlaced diamond rings, stand for Lorenzo the Magnificent and the Centaur for his enemies?

20

To be sure not to project on to paintings and statues meanings which the artists and their clients did not have in mind, it is prudent to start with literature, and with explicit discussions of implicit political meanings. The preface to the 1542 edition of Ariosto’s

Orlando Furioso

, written by the publisher, Gabriel Giolito, suggests that the poem has a political message, contrasting ‘the prudence and justice of an excellent prince’ with ‘the rashness and the negligence of an unwise king’. Did contemporaries really read this poem as if it were putting forward a political theory, as if Ariosto were another Machiavelli? Conversely, Machiavelli on occasion – in the seventeenth chapter of

The Prince

– quoted Virgil as an authority on politics, using Dido’s apology to Aeneas for her initial suspicions as evidence that a new prince has to be harsher than one who is well established.

When reading the literature of this period it is always worth entertaining the possibility, as contemporaries seem to have done, that the events narrated, whether real or imaginary, recent or remote, refer to or stand for incidents of the writer’s own day. Take for instance one of the Florentine religious plays of the period,

Santi Giovanni e Paolo

. Its particular interest in this context is that it was written by a ruler, Lorenzo the Magnificent. It is in fact much concerned with the political problems of the emperor Constantine. The rebellion of Dacia and its suppression by order of the emperor Constantine is reminiscent of the rebellion of the city of Volterra against Lorenzo and the suppression of that revolt by Federigo da Montefeltro. In the play, Constantine is made to emphasize the fact that he did everything for the common good. It looks as if Lorenzo was writing propaganda for himself.

21

Paintings and statues may also carry political meanings. The figures represented may be allegories in the sense that the apparent subject stands for someone else. Decoding these allegories is necessarily speculative, and interpretations are bound to be controversial, but the attempt at interpretation is not anachronistic. In this period, as in the Middle Ages, it was not uncommon to refer to living individuals as a ‘new’ or ‘second’ Caesar, Augustus, Charlemagne, and so on. For instance, the great preacher Fra Girolamo Savonarola called Charles VIII of France the ‘new Cyrus’ after

the famous king of Persia, and also the ‘new Charlemagne’.

22

The comparisons are a kind of secular parallel to the Old Testament prefigurations of the New, discussed earlier in this chapter. It is therefore not implausible to suggest, for example, that certain statues of David stand for Florence, or that Piero della Francesca’s paintings of the emperor Constantine refer to the Byzantine emperor John VII Palaeologus, who had visited Italy to enlist help in the defence of his capital, Constantinople (a city which had been founded by Constantine), against the Turks.

23