The Jim Crow Laws and Racism in United States History (5 page)

Read The Jim Crow Laws and Racism in United States History Online

Authors: David K. Fremon

Du Bois emerged as a leading Washington critic. He agreed with the idea of black self-help. But he believed that Washington’s policies “practically accepted the alleged inferiority of the Negro.”

9

Du Bois felt that blacks needed political rights in order to assure economic security.

In 1904, Washington, Du Bois, and other black leaders met in New York City’s Carnegie Hall. Du Bois presented a list of demands: full political rights for blacks, higher education for selected black youth, a national black periodical, establishment of a defense fund, and a strong fight in the courts for civil rights. The convention, largely attended by Washington followers, rejected the platform. Du Bois left the conference, determined to form his own civil rights group.

The Niagara Movement

In 1905, Du Bois sent a letter to sixty black professionals, inviting them to a meeting at Niagara Falls. About thirty showed up.

The meeting led to the formation of the Niagara Movement. It called for the cessation segregation, disfranchisement (lack of voting rights), and violence against blacks. The movement blamed white supremacists for black failures. Booker T. Washington’s nonconfrontational philosophy was another target.

Washington did not take kindly to the criticism directed at him. He hired the Pinkerton detective agency to find information he could use to discredit Niagara members. He also bribed newspapers to ignore the meeting.

Unfortunately, the poorly financed Niagara Movement failed to attract working-class blacks or sympathetic whites. Within five years, the Niagara Movement disbanded. However, the effort was not entirely wasted. Black leaders made connections that would serve them in later struggles.

NAACP

In 1908, a race riot broke out in Springfield, Illinois. Race-based outbreaks were not unknown in Southern cities, but a riot in the Illinois capital made it very clear that racism had always existed in the North as well as in the South.

Among the shocked Northerners was white journalist Mary White Ovington. She organized a conference to deal with discrimination. In 1909, Ovington’s National Negro Conference met in New York City. It led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP set up headquarters in New York in 1910. W.E.B. Du Bois was named editor of the

Crisis

, the organization’s newspaper. He was the only black leader active in the white-dominated organization.

The NAACP stressed legal action to correct existing evils. It sent investigators to record Southern atrocities in rural communities. One successful investigator was light-skinned, blue-eyed Walter White. A Georgia storekeeper told White, “Sheriffs and police and governors and prosecuting attorneys have got too much sense to mix in lynching-bees. If they do they know they might as well give up all idea of running for office any more—if something worse don’t happen to them.”

10

Washington saw this new group as a threat to his power. As with the Niagara Movement, he sought to discredit the NAACP and its leaders. The NAACP, however, survived the attacks. After Washington’s death, it attracted many of his former supporters.

By the time of Washington’s death, African Americans had several ways of coping with white racism. Some followed Washington’s accommodationist stance. Others supported the more activist NAACP. For thousands of blacks, there was a third solution. They left the South.

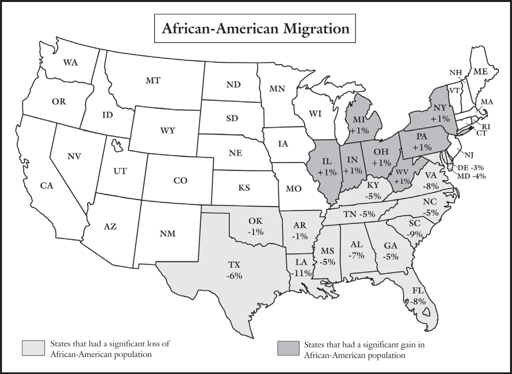

Image Credit: Enslow Publishers, Inc.

The migration of massive numbers of African Americans from the South to Northern cities dramatically changed the populations of many areas of the country.

Thousands of black Southerners stood at crowded railroad stations waiting for the Illinois Central and other northbound trains. Others waited miles away from the depot, at unmarked stops in the countryside. They knew it was dangerous to be seen leaving town.

They went for jobs that paid far more than those in the South. Some sought the bright lights and excitement of Chicago or New York. All went looking for freedom that was undreamed of in the land they were leaving behind.

“Not as Good as a White Man’s Dog”

Between 1865 and 1890, about forty thousand blacks moved west to Kansas. About one hundred eighty-five thousand black migrants went north in the 1890s. Many of these were affluent and educated residents of border states like Tennessee and Virginia. People such as former Congressman George White and journalist Ida B. Wells went north. These were among the “talented tenth” that W.E.B. Du Bois had hoped would lead the black population in the South.

They often moved to cities. By 1900, six cities—New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Memphis, and New Orleans—had at least fifty thousand black inhabitants. More than one quarter of African Americans were living in urban areas.

Those who left the farms could give many reasons for doing so. “There were no jobs, no education there,” claimed Margaret Burroughs, founder of Chicago’s Du Sable Museum of African American History.

1

The Houston Observer

asserted that the black Southerner “is kicked around, cuffed, lynched, burned, homes destroyed, daughters insulted and sometimes raped, has no vote or voice, and in some instances when he asks for pay receives a 2 x 4 over the head.”

2

One Mississippi man said simply, “Down here a Negro man is not as good as a white man’s dog.”

3

Efforts to Keep Blacks in the South

Southern whites might have abused and mistreated their black neighbors. But they did not want them to leave the South. If they left, who would do the backbreaking, lowpaying work? Poor whites would not stand jobs under slave-like conditions. Likewise, European immigrants to the United States refused to accept working conditions that were worse than those they left back home. Plantation owners maintained, “Negroes are a necessity to the South, and it is desirable that they should stay there and not migrate to the North.”

4

Whites tried different tactics to keep blacks from leaving the South. Some raised workers’ pay. Others suggested reforms, such as an end to lynchings. Some pointed out bad weather, high rents, or low-quality food in the North. If an unhappy migrant returned from the North, Southern newspapers headlined his or her story.

Leading Southern blacks also cautioned blacks to stay at home. Booker T. Washington, fearing a loss of funds from his white supporters, urged blacks to stay on the farm. Many black doctors, lawyers, and ministers faced a loss of income if their most prosperous clients fled. They, too, spoke out against migration.

If rewards or bribery did not work, whites resorted to force. In Macon, Georgia, police ousted several hundred northbound blacks from the city’s railroad station. In Americus, Georgia, local authorities boarded a train and arrested fifty blacks who were trying to leave. Stories like these alerted and frightened many black migrants. Often they left in the middle of the night, without notifying friends or neighbors. They caught the train miles from town to avoid detection by the local police or sheriff.

Many Northern companies sent labor agents to the South. These whites passed on information about jobs in Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland. Southern whites often refused to believe that their own racism led to black flight. They blamed the labor agents as outside troublemakers who were spoiling blacks’ happy lives in the South. By about 1917, labor agents were no longer needed. Letters from family and friends in the North provided better advertising than any stranger could give.

The

Defender

Chicagoan Robert S. Abbott started his newspaper in 1905, with an investment of twenty-five cents. By 1915, his

Chicago Defender

had become the largest and most influential black-owned paper in the nation.

The

Defender

was published in Chicago, but two thirds of its circulation was outside of the city. African Americans throughout the South read news that white Southern papers refused, and that black papers were afraid, to print.

Abbott refused to use the term

Negroes

. His

Defender

was by and for “the race.” Abbott’s editorial rule was simple: If it could benefit the race, he printed it. He used every opportunity to attack Southern abuses. For a popular series,

Below the Mason Dixon Line

, he sent reporters into small Southern towns. Local people told racial horror stories, which the reporters relayed to the Chicago-based newspaper.

Not surprisingly, Southern white authorities hated and feared the

Defender

. They went to any lengths possible to stop its circulation. In some towns, a person could be arrested for distributing the

Defender

. But Abbott befriended railroad workers, who helped sneak the paper to willing readers. These copies would be passed around to friends and neighbors, often until the ink smudged off the pages.

At first, Abbott advised blacks against moving. “The only thing to do is stick to the farm,” he wrote.

5

But by 1916, the

Defender

had a new message: “Come North.”

6

The Great Migration

Events came together, in America and abroad, in 1915 and 1916. These events altered the United States’ racial landscape.

The Southern agricultural economy depended on cotton, often the only profitable crop. Any misfortune to the cotton crop could mean disaster. When the boll weevil ruined much of the South’s cotton crop in 1915, blacks and whites alike suffered. When new machines made work for owners easier—at the expense of black workers—longtime farm hands became unemployed. Where could they go?

They went to cities in the North. Around the turn of the twentieth century, millions of European immigrants were arriving in the United States. They took jobs in a rapidly expanding factory-based economy. But World War I, which began in 1914, was ravaging Europe. The war, which the United States entered in 1917, cut off a much-needed labor supply. Immigration had to stop, and eventually, most able-bodied white men were called to fight in the military. Employers looked elsewhere for a workforce. In the Southern black population, they found willing and able employees.

More than half a million Southern blacks made their way north between 1916 and 1919. Most headed for cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, or Philadelphia. The action became known as the Great Migration. America had never seen such a mass movement of its people. Chicago’s black population doubled between 1910 and 1920. Detroit’s increased six-fold.

Some Southern towns and villages lost most or all of their black population. In many cases these emigrants moved to the same place in the North. “You had Louisiana clubs, Mississippi clubs, Alabama clubs,” recalled longtime Chicagoan Margaret Burroughs.

7

The Big City

Coming into Chicago on the Illinois Central, first-time travelers experienced a whole new world. In the South, most knew of farms and small towns. Now they saw huge factories belching smoke from chimneys that were taller than church steeples. If the train arrived at night, hundreds of city lights greeted them as they arrived at the downtown station. New arrivals noticed other differences. “It was strange to pause before a crowded newsstand and buy a newspaper without having to wait for a white man to be served,” commented author Richard Wright.

8

Blacks had to adjust to an entirely different lifestyle. Steel mills and meat packinghouses, not farms, were the main Chicago employers. These jobs offered far higher wages than farmwork, but they were physically dangerous. On Southern farms, African Americans followed the sun, working from sunup to sundown. Northern employers judged a workday by the clock, not the sun. Southern farm employers made allowances for older or disabled workers. Northern factories were not so generous.

The

Defender

pictured a Northern land of opportunity. Chicago, for example, had jobs, schools, and better housing than the South. Nightclubs promised an active social life. Chicago even had the American Giants, the best black baseball team in the nation.