The John Green Collection (51 page)

Read The John Green Collection Online

Authors: John Green

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Friendship, #Death & Dying, #Adolescence

“I think I’m gonna stay home tonight,” she said, and then turned her head to Colin and said, “Go.”

“Aww, Linds. I was just screwing with you.”

“Go,” she said again, and Colin hit the gas and shot off.

Colin was about to ask for an explanation of the scene when Lindsey turned to him and said very calmly, “It’s nothing—just an inside joke. So anyway, I read your notebook. I don’t really understand it all, but I at least

looked

at everything.”

Colin quickly forgot about the weirdness with TOC and asked, “What’d you think?”

“Well, first, it kept making me think about what we talked about when you first got here. When I told you I thought it was a bad idea to matter. I think I gotta take that back, because looking at your notes, I kept wanting to find a way to improve on your Theorem. I had this total hard-on for fixing it and proving to you that relationships

could

be seen as a pattern. I mean, it ought to work. People are so damned predictable. And then the Theorem wouldn’t be yours, it’d be ours, and I could—okay, this sounds retarded. But anyway, I guess I do want to matter a little—to be known outside Gutshot, or I wouldn’t have thought so much about it. Maybe I just want to be big-time without leaving here.”

Colin slowed as he approached a stop sign and then looked at her. “Sorry,” he said.

“Why sorry?”

“Because you couldn’t fix it.”

“Oh, but I did,” she said.

Colin brought the car to a full stop twenty feet in front of the stop sign and said, “Are you sure?” And she just kept smiling. “Well,

tell

me,” he pleaded.

“Okay, well I didn’t FIX it, but I have an idea. I suck at math—like really, really suck, so tell me if I have this wrong, but it seems like the only factor that goes into the formula is where each person fits on the Dumper/Dumpee scale, right?”

“Right. That’s what the formula’s about. It’s about getting dumped.”

“Yeah, but that’s not the only factor in a relationship. There’s, like, age. When you’re nine, your relationships tend to be shorter and less serious and more random than when you’re forty-one and desperate to get married before your flow-o’-eggs dries up, right?”

Colin turned away from Lindsey and looked at the intersecting roads before him, both utterly abandoned. He thought it through for a while. It seemed so obvious now—many discoveries do. “More variables,” he announced enthusiastically.

“Right. Like I said—age, for starters. But a lot of things go into it. I’m sorry, but attractiveness matters. There’s this guy who just joined the Marines, but last year he was a senior. He was like 210 pounds of chiseled muscle, and I love Colin and everything, but this guy was dead sexy and also really sweet and nice, and he drove a tricked-out Montero.”

“I hate that guy,” Colin said.

Lindsey laughed. “Right, you totally would. But anyway, total Dumper. Self-professed proponent of the 4 Fs: find ’em, feel ’em, fug ’em, and forget ’em. Only he made the mistake of dating the only person hotter than him in Middle Tennessee—Katrina. And he became the clingiest, neediest, whimperingest little puppy dog and finally Katrina had to ditch him.”

“But it’s not just physical attraction,” Colin said, reaching into his pocket for his pencil and notepad. “It’s how attractive you find the person and how attractive they find you. Like, say there’s this girl who’s very pretty, but as it happens, I have a weird fetish and only like girls with thirteen toes. Well, I might be the Dumper if she happens to be ten-toed and only gets turned on by skinny guys with glasses and Jew-fros.”

“And really green eyes,” Lindsey added nonchalantly.

“What?”

“I was complimenting you,” she said.

“Oh. Mine. Green. Right.”

Smooth, Singleton. Smooth.

“Anyway, I think it needs to be way more complicated. It needs to be so complicated that a math tard like me won’t understand it in the

least.

”

A car pulled up behind them and honked, so Colin returned to driving, and by the time they were in the cavernous parking lot of the nursing home, they had settled on five variables:

Age (A)

62

Popularity Differential (C)

63

Attractiveness Differential (H)

64

Dumper/Dumpee Differential (D)

65

Introvert/Extrovert Differential (P)

66

They sat in the car together with the windows down, the air warm and sticky but not stifling. Colin sketched possible new concepts and explained the math to Lindsey, who made suggestions and watched his sketching. Within thirty minutes, he was cranking out the basic she-broke-up-with-him frowny-face graph

67

for several Katherines. But he couldn’t get the timing right. Katherine XVIII, who cost him months of his life, didn’t look like she lasted any longer, or mattered any more, than the 3.5 days he spent in the arms of Katherine V He was creating too simple a formula. And he was

still trying to do it completely randomly.

What if I square the attractiveness variable? What if I put a sine wave here or a fraction there

? He needed to see the formula not as math, which he hated, but as language, which he loved.

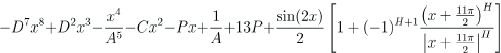

So he started thinking of the formula as an attempt to communicate something. He started creating fractions within the variables so that they’d be easier to work with in a graph. He began to see before even inputting the variables how different formulas would render the Katherines, and as he did so the formula grew increasingly complicated, until it began to seem almost—how to put this not so dorkily—well, beautiful. After an hour parked in the car, the formula looked like this:

“I think that’s close,” he said finally.

“And I sure as shit don’t understand it at all, so you’ve succeeded in my eyes!” She laughed. “Okay, let’s go hang with the oldsters.”

• • •

Colin had only been in a nursing home once. He and his dad drove to Peoria, Illinois, one weekend when Colin was eleven to visit Colin’s great-great-aunt Esther, who was in a coma at the time and therefore not very good company.

So he was pleasantly stunned by Sunset Acres. At a picnic table on the lawn outside, four old women, all wearing broad, straw hats, were playing a card game. “Is that Lindsey Lee Wells?” one of the women asked, and then Lindsey brightened and hastened over to the table. The women laid down

their cards to hug Lindsey and pat her puffy cheeks. Lindsey knew them all by name—Jolene, Gladys, Karen, and Mona—and introduced Colin to them, whereupon Jolene took off her hat, fanned her face, and said, “My, Lindsey, you

do

have a nice-looking boyfriend, don’t you? No wonder you don’t come ’round to visit us no more.”

“Aw, Jolene, he ain’t my boyfriend. I’m sorry I haven’t been around as much. I been so busy with school, and Hollis works me like a dog down at the store.”

And then they took to discussing Hollis. It took fifteen minutes before Colin could even get his tape recorder started to ask the four questions they’d come there to ask, but he didn’t mind, first because Jolene thought he was “nice-looking,” and second because they were such a relaxed bunch of old people. For example, Mona, a woman with liver spots and a gauze patch over her left eye, answered the question, “What’s special about Gutshot?” by saying, “Well for starters that mill has got a right-good pension plan. I been retired for thirty years and Hollis Wells

still

buys my diapers. That’s right, I use ’em! I pee myself when I laugh,” she said gleefully, and then laughed disturbingly hard.

And Lindsey, it seemed to Colin, was some kind of rock star among the oldsters. As word filtered through the building that she’d arrived, more and more of them made their way to the picnic tables outside and hovered around Lindsey. Colin went from person to person, recording their answers to the questions. Eventually, he just sat down and let Lindsey throw people his way.

His favorite interview was with a man named Roy Walker. “Well I can’t imagine,” Roy said, “why on earth anyone would want to hear from me. But I’m happy to chat.” Roy was starting to tell Colin about his former job as night-shift plant manager of Gutshot Textiles, but then he stopped suddenly and said, “Look how they’re all loving on little Lindsey. We all raised that girl up. I used to see her once a week or more—we knew her when she was a baby and we knew her when you couldn’t tell her from a boy and we knew her when she had blue hair. She used to sneak me in one Budweiser beer every Saturday, bless her heart. Son, if there’s one thing I know,” and Colin thought about how old people always like to tell you the one thing they know, “it’s that there’s some people in this world who you can just love and love and love no matter what.”

Colin followed Roy over to Lindsey then. Lindsey was twisting a lock of her hair casually, but staring intently at Jolene.

“Jolene, what’d you just say?”

“I was telling Helen that your mama is selling two hundred acres of land up Bishops Hill to my boy Marcus.”

“Hollis is selling land on Bishops Hill?”

“That’s right. To Marcus. I think Marcus wants to build himself some houses up there, build a little—I don’t remember what he calls it.”

Lindsey half-closed her eyes and sighed. “A subdivision?” she asked.

“That’s right. Subdivision. Up there on the hill, I guess. Nice views, anyway.”

Lindsey became quiet after that, her big eyes staring off into the distance at the fields behind the nursing home. Colin sat there and listened to the old folks talking, and then finally Lindsey grabbed his arm just above the elbow and said, “We should get going.”

As soon as the Hearse’s doors were shut, Lindsey mumbled as if to herself, “Mom would never sell land. Never. Why is she doing that?” It occurred to Colin that he’d never before heard Lindsey refer to Hollis as Mom. “Why would she sell land to that guy?”

“Maybe she needs money,” Colin offered.

“She needs money like I need a goddamned hole in my head. My great-grandfather

built

that factory. Dr. Fred N. Dinzanfar. We aren’t hurting for money, I promise you.”

“Was he Arab?”

“What?”

“Dinzanfar.”

“No, he wasn’t Arab. He was from Germany or something. Anyway, he spoke German—so does Hollis, that’s how I know it. Why do you always ask such ridiculous questions?”

“Jeez. Sorry.”

“Oh, whatever, I’m just confused. Who cares. On to other things. It’s fun hanging out with the oldsters, isn’t it? You wouldn’t think it, but they’re cool as hell. I used to visit those people at their houses—most of them weren’t in the Home then—almost every day. I’d just go from house to house, getting fed and getting hugged on. Those were the pre-friend days.”

“They certainly seemed to adore you,” Colin said.

“Me? The ladies couldn’t talk about anything but how hot you were. You’re missing a whole demographic of Katherines by not chasing the over-eighty market.”

“It’s funny how they thought we were dating,” Colin said, glancing over at her.

“How’s that funny?” she asked, holding his gaze.

“Um,” he said. Distracted from the road, Colin watched as she gave him the slightest version of her inimitable smile.

61

Television was invented by a kid. In 1920, the memorably named Philo T. Farnsworth conceived the cathode ray vacuum tube used in most all twentieth-century TV sets. He was fourteen. Farnsworth built the first one when he was just twenty-one. (And shortly thereafter went on to a long and distinguished career of chronic alcoholism.)

62

To get this variable, Colin took the two people’s average age and subtracted five. By the way, all the footnotes on this page have math in them and are therefore

strictly optional.

63

Which Colin arrived at by calculating the popularity difference between Person A and Person B on a scale of 1 to 1,000 (you can approximate) and then dividing by 75—positive numbers if the girl is more popular; negative if the guy is.

64

Which is calculated as a number between 0 and 5 based on the difference in attraction to each other. Positive numbers if the boy is more attracted to the girl; negative if vice versa.

65

Between 0 and 1, the relative distance between the two people on the Dumper/Dumpee range. A negative number if the boy is more of a Dumper; positive number if the girl is.

66

In the Theorem, this is the difference in outgoingness between two people calculated on a scale that goes from 0 to 5. Positive numbers if the girl is more outgoing; negative if the guy is.