The Kennedy Brothers: The Rise and Fall of Jack and Bobby (31 page)

Read The Kennedy Brothers: The Rise and Fall of Jack and Bobby Online

Authors: Richard D. Mahoney

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Political, #History, #Americas, #20th Century

Edmund Wilson had once likened men at war to “a school of fish, which will swerve, simultaneously and apparently without leadership, when the shadow of the enemy appears.” As the American military swerved and darted toward war, the role of the secretary of defense became critical. To maintain a firm chain of command, McNamara began living in his office.

185

As George Ball later commented, had the occupant of that office been someone like Reagan defense secretary Caspar Weinberger, the missile crisis may well have ended in a shooting war.

186

At the first meeting to deal with the crisis, Bobby initially seemed interested in a pretext to attack Cuba, suggesting the United States might “sink the

Maine

or something.”

187

Kenny O’Donnell (who attended this first meeting) remembered that Bobby stood, arms crossed, about three feet behind the far end of the table, mostly listening and walking back and forth. Everyone else was sitting. The view of about two-thirds of the group (that came to be known as Ex Comm) was to launch an immediate air strike. According to O’Donnell, Bobby studied his brother’s face as various members spoke. Suddenly, he walked forward to the table and scribbled a note on a piece of paper, folded it, and walked over and gave it to Ted Sorensen.

188

(In RFK’s memoir of the crisis,

Thirteen Days

, he states that he gave this note directly to the president.) The note read: “I now know how Tojo felt when he was planning Pearl Harbor.”

Secretary Rusk later said in an interview that writing and passing a note during such a meeting was “wholly inappropriate . . . the gravest question, that included the fate of the world, the most consequential measures, were before us. . . . But, of course, this was Bobby Kennedy — couldn’t wait, wouldn’t accept the chain of command . . . and, of course, everyone was wondering: ‘What the hell did [the note] say?’”

189

George Ball saw it differently: “To place a rational template on an act of pure instinct,” he said in an interview,

is like trying to explain the movement of an athlete. At the time, I’m not sure I knew what it meant, but later it became clearer to me. First, Bobby was saying to his brother: “I can turn this group around for you.” Second, it reminded everyone how strong and seamless the relationship between the brothers was. Third, it totally denigrated the air strike option by likening it to Japan’s sneak attack — an act of pure infamy. Dean Acheson later wrote that it was a false analogy. And it was. But that’s also a rational reaction to the Tojo remark. In a nonrational way, Bobby spiked all the moral and operational tidiness of the surgical strike.

190

After that first meeting, the attorney general walked back to the White House with his brother, who, according to Bobby, “decided that he would not attend all the meetings of our committee.” Bobby later explained that the purpose of this was to “keep discussions from being inhibited. . . . Personalities change when the president is present.”

191

But the tactic was more far-reaching than this. First, with the president absent, Ex Comm could deliberate without entering what is called the “decisional chute.” The move, in short, bought time. Second, the president did not have to react on the record to proposed courses of action, as he had so prematurely in the Bay of Pigs crisis. He could choose his shots and slowly build his votes through his brother, Sorensen, and McNamara. Kennedy may have been exaggerating when he said that Congress would impeach him if he did nothing, but he understood that congressional leaders (and opinion makers at large) wouldn’t buy the idea of a blockade if Ex Comm and the Joint Chiefs weren’t behind it, at least officially. As James Blight and David Welch have concluded, there was a collision of worldviews between the hawks and doves. “The hawks’ Cuban missile crisis was relatively understandable, predictable, controllable, and safe. The doves’, on the other hand, was inexplicable, unpredictable, uncontrollable, and above all, dangerous. The doves felt enormous anxiety throughout, while the hawks felt virtually none.”

192

The Kennedy brothers would have to bring these worlds together.

For six days, the Ex Comm communed with open candor but in total secrecy. The interlude, as George Ball commented later, proved critical to the outcome for it bled down emotion and enhanced caution. As McNamara later commented, “In every crisis you will never know what you need to know, and therefore you should behave cautiously.” The idea of the doves was to “turn the screw” slowly — to start with the blockade (now called a quarantine) and then slowly increase the pressure on the Soviets. Above all, there should be no irrevocable actions.

193

To preserve an appearance of business as usual, the president flew to New Haven on Wednesday the seventeenth to give a speech at Yale, where he was booed by students protesting for a tougher Cuba policy.

194

Late Wednesday afternoon, also to preserve cover, Kennedy met with Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko at the White House. Because the Russians had lied about the missiles, and because his administration had not yet resolved what to do in response, Kennedy chose not to confront him. (At a conference held in 1991, Russian scholars and policymakers suggested that had Kennedy confronted Gromyko, it might have provided an opening to engage the Soviet Union diplomatically.)

195

Instead, Kennedy listened, somewhat astonished, as Gromyko reiterated Russia’s peaceful intentions vis-à-vis Cuba. All weapons being shipped there, he told the president, were defensive. Kennedy then had an aide bring him his statement of September 4 regarding the consequences of placing offensive weapons in Cuba and read it to Gromyko.

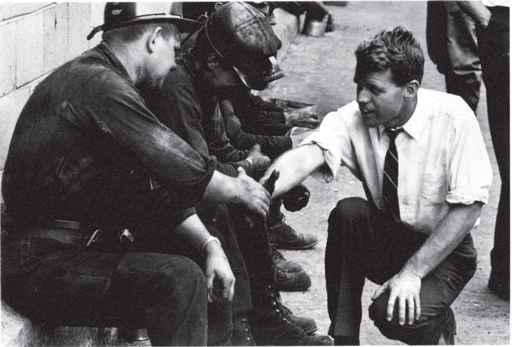

The Kennedy brothers bear down on a Teamsters official at the McClellan Committee hearings in May 1957.

Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

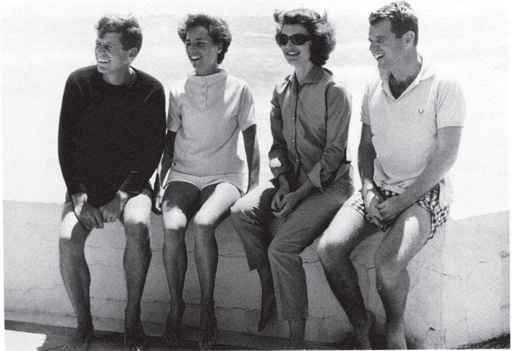

“He’s always there for you,” Jackie said of Bobby. Here they are — with Jack and daughter Caroline — sailing off Hyannis Port in August 1959.

Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

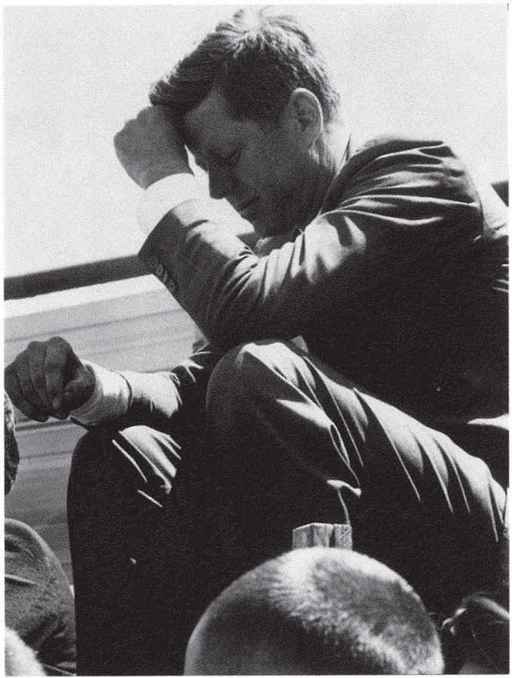

In the West Virginia primary in May 1960, Jack — as always — managed to conceal the fact that he was in pain. Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

On election night, November 8, 1960, Bobby has a word with aide Pierre Salinger as Eunice Kennedy Shriver listens.

Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

Bobby worked night and day in the West Virginia primary but in the end it was Joe Kennedy’s money that bought the election.

Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

Here the two couples — Jack and Jackie, Bobby and Ethel — are pictured in Palm Beach, 1958. Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

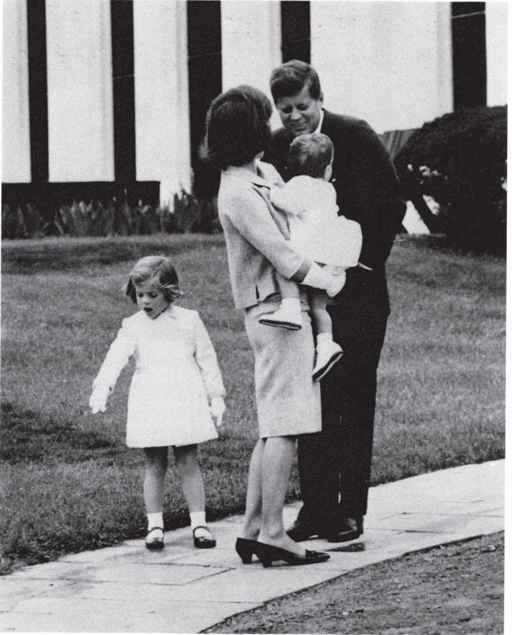

Jack may have been a wayward husband, but he was also a doting father. Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.

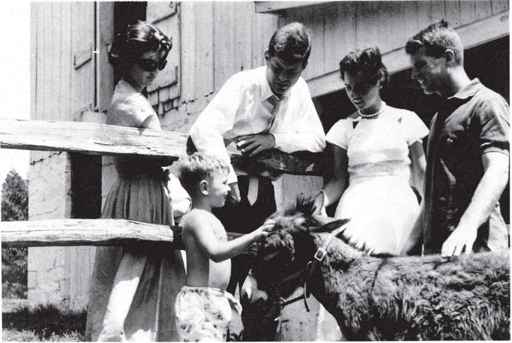

The dark glasses were part of her silent statement — Jackie (here pictured at Hickory Hill in 1958) detested politics and its impact on her marriage.

Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library/Look Photo Collection.