The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (63 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

At this point, defenders of the standard are likely to pull out the notorious double negative, as in

I can’t get no satisfaction

. Logically speaking, the two negatives cancel each other out, they teach; Mr. Jagger is actually saying that he is satisfied. The song should be entitled “I Can’t Get

Any

Satisfaction.” But this reasoning is not satisfactory. Hundreds of languages require their speakers to use a negative element somewhere within the “scope,” as linguists call it, of a negated verb. The so-called double negative, far from being a corruption, was the norm in Chaucer’s Middle English, and negation in standard French—as in

Je ne sais pas

, where

ne

and

pas

are both negative—is a familiar contemporary example. Come to think of it, Standard English is really no different. What do

any, even

and

at all

mean in the following sentences?

I didn’t buy any lottery tickets.

I didn’t eat even a single French fry.

I didn’t eat fried food at all today.

Clearly, not much: you can’t use them alone, as the following strange sentences show:

I bought any lottery tickets.

I ate even a single French fry.

I ate fried food at all today.

What these words are doing is exactly what

no

is doing in nonstandard American English, such as in the equivalent

I didn’t buy no lottery tickets

—agreeing with the negated verb. The slim difference is that nonstandard English co-opted the word

no

as the agreement element, whereas Standard English co-opted the word

any;

aside from that, they are pretty much translations. And one more point has to be made. In the grammar of standard English, a double negative does

not

assert the corresponding affirmative. No one would dream of saying

I can’t get no satisfaction

out of the blue to boast that he easily attains contentment. There are circumstances in which one might use the construction to deny a preceding negation in the discourse, but denying a negation is not the same as asserting an affirmative, and even then one could probably only use it by putting heavy stress on the negative element, as in the following contrived example:

As hard as I try not to be smug about the misfortunes of my adversaries, I must admit that I can’t get

no

satisfaction out of his tenure denial.

So the implication that use of the nonstandard form would lead to confusion is pure pedantry.

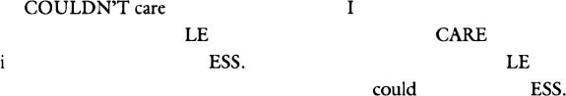

A tin ear for prosody (stress and intonation) and an obliviousness to the principles of discourse and rhetoric are important tools of the trade for the language maven. Consider an alleged atrocity committed by today’s youth: the expression

I could care less

. The teenagers are trying to express disdain, the adults note, in which case they should be saying

I couldn’t care less

. If they could care less than they do, that means that they really do care, the opposite of what they are trying to say. But if these dudes would stop ragging on teenagers and scope out the construction, they would see that their argument is bogus. Listen to how the two versions are pronounced:

The melodies and stresses are completely different, and for a good reason. The second version is not illogical, it’s

sarcastic

. The point of sarcasm is that by making an assertion that is manifestly false or accompanied by ostentatiously mannered intonation, one deliberately implies its opposite. A good paraphrase is, “Oh yeah, as if there was something in he world that I care less about.”

Sometimes an alleged grammatical “error” is logical not only in the sense of “rational” but in the sense of respecting distinctions made by the formal logician. Consider this alleged barbarism, brought up by nearly every language maven:

Everyone returned to their seats.

Anyone who thinks a Yonex racquet has improved their game, raise your hand.

If anyone calls, tell them I can’t come to the phone.

Someone dropped by but they didn’t say what they wanted.

No one should have to sell their home to pay for medical care.

He’s one of those guys who’s always patting themself on the back, [an actual quote from Holden Caulfield in J. D. Salinger’s

Catcher in the Rye

]

They explain:

everyone

means

every one

, a singular subject, which may not serve as the antecedent of a plural pronoun like

them

later in the sentence. “Everyone returned to

his

seat,” they insist. “If anyone calls, tell

him

I can’t come to the phone.”

If you were the target of these lessons, at this point you might be getting a bit uncomfortable.

Everyone returned to his seat

makes it sound like Bruce Springsteen was discovered during intermission to be in the audience, and everyone rushed back and converged on his seat to await an autograph. If there is a good chance that a caller may be female, it is odd to ask one’s roommate to tell

him

anything (even if you are not among the people who are concerned about “sexist language”). Such feelings of disquiet—a red flag to any serious linguist—are well founded in this case. The next time you get corrected for this sin, ask Mr. Smartypants how you should fix the following:

Mary saw everyone before John noticed them.

Now watch him squirm as he mulls over the downright unintelligible “improvement,”

Mary saw everyone before John noticed him

.

The logical point that you, Holden Caulfield, and everyone but the language mavens intuitively grasp is that

everyone

and

they

are not an “antecedent” and a “pronoun” referring to the same person in the world, which would force them to agree in number. They are a “quantifier” and a “bound variable,” a different logical relationship.

Everyone returned to their seats

means “For all X, X returned to X’s seat.” The “X” does not refer to any particular person or group of people; it is simply a placeholder that keeps track of the roles that players play across different relationships. In this case, the X that comes back to a seat is the same X that owns the seat that X comes back to. The

their

there does not, in fact, have plural number, because it refers neither to one thing nor to many things; it does not refer at all. The same goes for the hypothetical caller: there may be one, there may be none, or the phone might ring off the hook with would-be suitors; all that matters is that every time there is a caller, if there is a caller, that caller, and not someone else, should be put off.

On logical grounds, then, variables are not the same thing as the more familiar “referential” pronouns that trigger number agreement (

he

meaning some particular guy,

they

meaning some particular bunch of guys). Some languages are considerate and offer their speakers different words for referential pronouns and for variables. But English is stingy; a referential pronoun must be drafted into service to lend its name when a speaker needs to use a variable. Since these are not real referential pronouns but only homonyms of them, there is no reason that the vernacular decision to borrow

they, their, them

for the task is any worse than the prescriptivists’ recommendation of

he, him, his

. Indeed,

they

has the advantage of embracing both sexes and feeling right in a wider variety of sentences.

Through the ages, language mavens have deplored the way English speakers convert nouns into verbs. The following verbs have all been denounced in this century:

to caveat

to nuance

to dialogue

to parent

to input

to access

to showcase

to intrigue

to impact

to host

to chair

to progress

to contact

As you can see, they range from varying degrees of awkwardness to the completely unexceptionable. In fact, easy conversion of nouns to verbs has been part of English grammar for centuries; it is one of the processes that make English English. I have estimated that about a fifth of all English verbs were originally nouns. Considering just the human body, you can

head a committee, scalp the missionary, eye a babe, nose around the office, mouth the lyrics, gum the biscuit, begin teething, tongue each note on the flute, jaw at the referee, neck in the back seat, back a candidate, arm the militia, shoulder the burden, elbow your way in, hand him a toy, finger the culprit, knuckle under, thumb a ride, wrist it into the net, belly up to the bar, stomach someone’s complaints, rib your drinking buddies, knee the goalie, leg it across town, heel on command, foot the bill, toe the line

, and several others that I cannot print in a family language book.

What’s the problem? The concern seems to be that fuzzy-minded speakers are slowly eroding the distinction between nouns and verbs. But once again, the person in the street is not getting any respect. Remember a phenomenon we encountered in Chapter 5: the past tense of the baseball term

to fly out

is

flied, not flew;

similarly, we say

ringed the city

, not

rang

, and

grandstanded

, not

grandstood

. These are verbs that came from nouns (

a pop fly, a ring around the city

, a

grandstand

). Speakers are tacitly sensitive to this derivation. The reason they avoid irregular forms like

flew out

is that their mental dictionary entry for the baseball verb

to fly

is different from their mental dictionary entry for the ordinary verb

to fly

(what birds do). One is represented as a verb based on a noun root; the other, as a verb with a verb root. Only the verb root is allowed to have the irregular past-tense form

flew

, because only for verb roots does it make sense to have

any

past-tense form. The phenomenon shows that when people use a noun as a verb, they are making their mental dictionaries more sophisticated, not less so—it’s not that words are losing their identities as verbs versus nouns; rather, there are verbs, there are nouns, and there are verbs based on nouns, and people store each one with a different mental tag.

The most remarkable aspect of the special status of verbs-from-nouns is that everyone unconsciously respects it. Remember from Chapter 5 that if you make up a new verb based on a noun, like someone’s name, it is always regular, even if the new verb sounds the same as an existing verb that is irregular. (For example, Mae Jemison, the beautiful black female astronaut,

out-Sally-Rided Sally Ride

, not

out-Sally-Rode Sally Ride

.) My research team has tried this test, using about twenty-five new verbs made out of nouns, on hundreds of people—college students, respondents to an ad we placed in a tabloid newspaper asking for volunteers without college education, school-age children, even four-year-olds. They all behave like good intuitive grammarians: they inflect verbs that come from nouns differently from plain old verbs.

So is there anyone, anywhere, who does not grasp the principle? Yes—the language mavens. Look up

broadcasted

in Theodore Bernstein’s

The Careful Writer

, and here is what you will find:

If you think you have correctly forecasted the immediate future of English and have casted your lot with the permissivists, you may be receptive to

broadcasted

, at least in radio usage, as are some dictionaries. The rest of us, however, will decide that no matter how desirable it may be to convert all irregular verbs into regular ones, this cannot be done by ukase, nor can it be accomplished overnight. We shall continue to use

broadcast

as the past tense and participle, feeling that there is no reason for

broadcasted

other than one of analogy or consistency or logic, which the permissivists themselves so often scorn. Nor is this position inconsistent with our position on

flied

, the baseball term, which has a real reason for being. The fact—the inescapable fact—is that there are some irregular verbs.