The Last Boy (31 page)

Authors: Jane Leavy

Having “paid his dues to pain,” Addie wrote, Mantle “received an ovation from the crowd. Then he told Houk,

I’m playing.”

Houk hadn’t seen the wound. “My God, you’d better not play,” The

Major said after assessing the damage. But the doctors had assured him that playing wasn’t going to hurt Mantle further. It was just going to hurt. Mauch bandaged and padded and cushioned the area as best he could. “They taped a big rubber doughnut as a protection so that if he bumped it, it would give him a cushion on the sore,” DeMaestri said. “If you just touched it, my God, such pain you couldn’t believe it.”

When the Yankees took the field, Maris was jeered; Mantle was cheered. Lovell Mantle, who had not seen her son play in eleven years, was at the game. Asked if she thought she would bring the Yankees luck, she replied, “I don’t think Mickey is superstitious.” Mantle went hitless, striking out twice. But his wise counsel proved decisive when Blanchard consulted him before pinch-hitting against Bob Purkey in the eighth inning. “He’s going to throw you a slider first pitch for a strike,” Mantle said. “Then he’s gonna come back with knuckleballs.”

Blanchard homered on a first-pitch slider to tie the score. When he returned to the dugout, Mantle said, “Hey, Blanch, you owe me a six-pack.”

“I bought him a case,” Blanchard said.

Maris won the game with a ninth-inning home run.

Game 4 was a rematch of the Series opener: Whitey Ford versus Jim O’Toole.

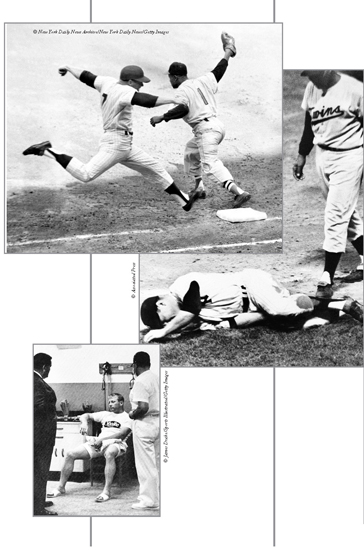

Mantle led off in the top of the second inning with a hard ground ball to third. Halfway down the first base line, he pulled up. The effort had yanked the unstitched wound apart. Blood began to seep through the layers of protective padding. Mantle tried to disguise the spreading stain with his glove when he returned to the dugout after the bottom of the third inning. “Clete Boyer went to Ralph Houk and says, ‘Do you know Mickey’s bleeding?’” Prudenti said. “Ralph went over and says, ‘Let me see that leg. Move the glove.’

“And Mick was trying to hide it. And Ralph Houk says, ‘Come on Mickey, I’m takin’ you out.’

“He says, ‘Aw, that ain’t bad. It’s nothing.’

“You’re bleeding like a stuck hog,” Houk said, summoning the trainer.

“Mickey didn’t believe him,” Blanchard said. “He had to drop his pants to look at the red spot, the blood. He couldn’t see down the back of his pants. He looked down and there it was. He said, ‘Okay,’ and he left. Boy, talk about a competitor.”

After the game Mantle gave a somewhat different account to Joe Reichler, the baseball writer for the Associated Press. Naked except for the bandage on his hip, he told Reichler he knew he would have to quit after the third inning. “At first I could only feel the blood running down my leg,” Mantle said. “Then I could see it through my ball suit. When I came in at the end of the inning, I told Ralph I couldn’t run and he said he wanted me to bat and if I got a hit, he would take me out for a pinch runner.”

Maris led off the fourth inning with a walk. Mantle walked gingerly to the plate, took two pitches for balls, and fouled off the third. He sent Jim O’Toole’s fourth pitch on a low line drive to left center field. Any other time, it would have been a double. Mantle had to stop at first; Maris went to third; he would score the game’s first run. From the mound, O’Toole could see “the bloody mess on his leg.” O’Toole saluted his courage fifty years later: “He may have caused it all himself, but God bless him.”

Mantle left the game for a pinch runner and received an ovation from his teammates when he reached the Yankee bench.

The entrance to the visitors’ clubhouse at Crosley Field was through the home dugout. Everyone in the ballpark understood the significance when Mantle made his way across the field, down the steps, and into the shadows.

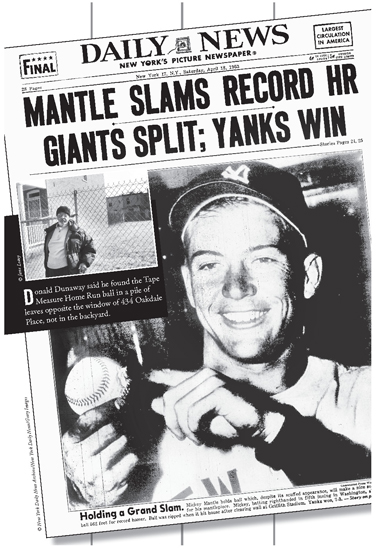

S

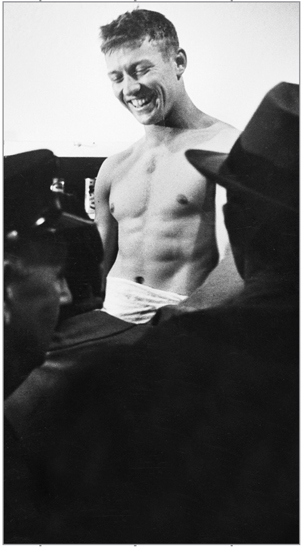

ubway series: Winner’s grin spreading over the face of the Yankees’ twenty-year-old star, Mickey Mantle. In the visiting clubhouse at Ebbets Field, Mantle was elevated and venerated after hitting the game 7 home run that decided the 1952 World Series. He had every reason to smile. It was a smile “quite unlike any other,” Tim McCarver said, “almost a measure of a man.”

I

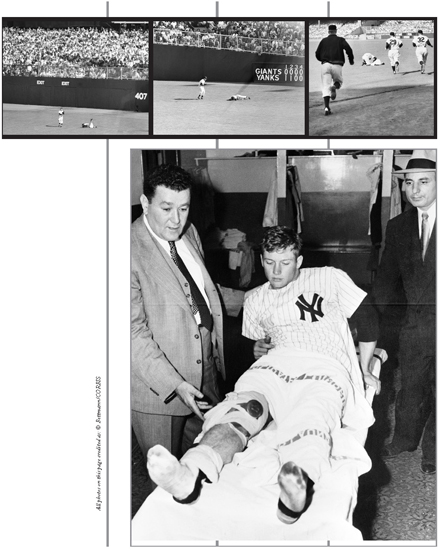

n the fifth inning of game 2 of the 1951 World Series, New York’s other rookie center fielder, Willie Mays, hit a tweener to right center field. The collision of fates was almost operatic: Mays, Mantle, and DiMaggio triangulating the future of the game. Mantle caught a spike in a drain trying not to run into Joe “Fuckin’” DiMaggio. It was the turning point of a life that had just begun. A day later his father was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Mantle’s knee and heart were never the same. He never looked that young again.

T

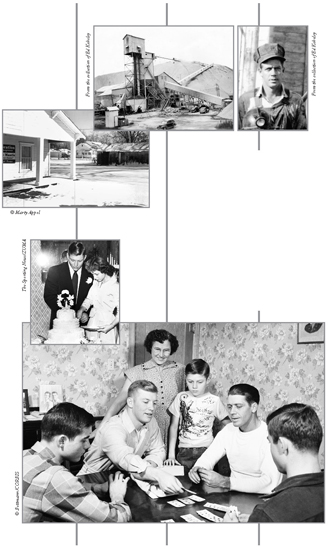

o New York wise guys, Commerce, Oklahoma (

top

), sounded like a made-up name.

Above

: The mining shack where the Mantles lived for a decade, the corrugated metal shed where he and Mutt practiced every day at 4

P.M.

, and the toxic legacy of the lead and zinc mines.

Left:

The sign announcing the renovation of Mantle’s childhood home was stolen off the front porch.

Below

: Dying, Mutt told his son all he wanted for Christmas in 1951 was a wedding. In the last family photograph, taken two weeks before the marriage of Mickey and Merlyn, Mantle plays the hand he’s dealt.

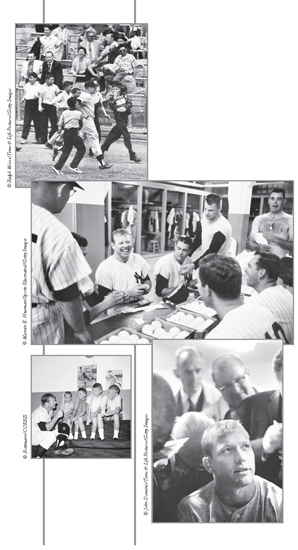

S

urrounded by adoring fans, or teammates, or reporters, or by the four young sons who rarely saw him, Mantle was seldom alone. In the Yankee clubhouse, where he was his happiest and best self, “the loneliness of greatness” was still palpable.

H

e soared, he crashed, he persevered.

H

e swung and he missed and he hurt. Later, he admitted how much he had hurt himself.

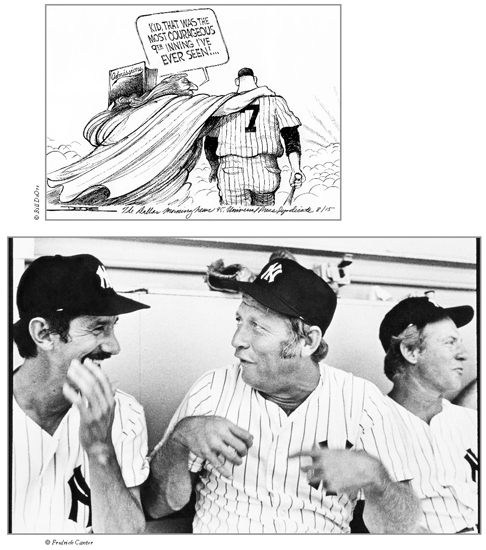

T

op

: The drawing of Mantle at the Pearly Gates appeared in the

Dallas Morning News

the day after his death. His wife later outbid one of his drinking buddies for the original art, cartoonist Bill DeOre said, because she blamed them for contributing to his downfall.

Bottom

: Mantle and pals, Billy Martin and Whitey Ford, at Old Timers’ Day at Shea Stadium in 1975. He was the Last Boy in the last decade ruled by boys. “He never grew up, and it ruined him,” teammate Jerry Coleman said.