The Last Drive (7 page)

Authors: Rex Stout

“I'm sorry, sirâ”

“Keep off, Harry!”

The detective sat harder. Gil's body twisted feebly about. Young Adams seemed to hesitate an instant, then he stooped swiftly and encircled Rankin with his arms. The detective struggled, but in vain; he was still all but exhausted, and the strength of the young athlete was too much for him. Inexorably he was dragged from his captive and across the sidewalk; he tried to twist about, but the arms held him in a grip of steel. The unknown, left free, stirred and turned, lifting himself to his knees; there he stopped for a moment, swaying as if dazed, then hastily scrambled to his feet. Young Adams was calling to him quietly:

“Get in the car, Gil, and beat it. Quick! Come on, pull yourself together! Beat it, I say! You might have knownâI'll phone you in the morning. Lay low till you hear from me.”

The unknown lost no time, nor wasted breath in speech. For a second he stood uncertainly in the attitude of a man who asks “Where am I?” then turned without a word and staggered to the roadster and pulled himself in. The engine was still running. A jerk of a lever, and the car leaped forward into the night.

Harry waited till the red light had completely disappeared in the darkness, then released his hold on the detective and stepped aside.

“I'm sorry, sirâ”

Rankin made no reply. He was feeling gingerly about his shoulder for broken bones, and moving his arm cautiously up and down. It seemed to work all right. Now that the passion of battle was leaving him, he felt a little silly as he looked at the young man standing there quietly before him in the peaceful moonlight.

“Who the deuce is Gil?” he asked abruptly.

Then as Harry hesitated with his reply the detective looked at his watch, shook himself together and brushed the dust from his clothing.

“Nearly one o'clock,” he observed. “No use standing here. Let's get back to Greenlawn. You can tell me about it on the way.”

So it was as they trudged back along the moonlit country road, side by side, that Harry explained. Until they reached the border of the village he was silent, and when he began to speak his words came jerkily.

“I'll have to tell you about it, I suppose,” he said slowly, “so you'll understand my position. Not that there's anything really wrong about it as far as I'm concerned, but Iâwell, I'm not very proud of it.”

They walked on a moment in silence, then he continued:

“GilâGil Warnerâwas a classmate of mine at college. He did me a mighty good turn one nightâin fact he saved my life and more, too. But that hasn't anything to do with the worst part of the businessâthat is, my worst partâthe beginning.

“I never really liked Gil, but I was under a great obligation to him, so when he came to New York I saw more or less of himâgot him invited places and so on. Finally, about four months ago, he started after me to go in on a stock speculation with him. At first I wouldn't listen, but he talked it up and it really sounded good. He wanted me to interest Uncle Carson in it, and at length I consented; but I didn't have much success. Uncle looked into it a little and turned it down cold; said it wasn't worth a cent.”

“Did the Colonel meet Warner?” the detective put in.

“No. I didn't mention Gil's name. Then Gil got after me to go in on my own hook. You know, I haveâ

had

âabout a hundred thousand left me by father, in good securities. I refused twenty times, but he kept after me, and at last I gave in. That's where I was a blanked ass. But it really looked good to me. I went to Mr. Mawsonâ”

“What did you go to Mawson for?”

“He handled things for me. He has since father's death. I told him all about it, and he agreed to help me realize on the securities without telling uncle. I got it and put it all in United Traffic.

Weâ”

“In what?”

“United Traffic. What's the matter? Oh, you've heard how it blew up, of course. I said I was a blanked ass.”

The detective had stopped short with an expression of surprise on his face. Now he whistled a little, as the surprise deepened into perplexity.

“Yes, I've heard how it blew up,” he replied as he moved on again. “But it wasn't that. It wasânothing. Go on.”

“That's all. It blew up. The bottom fell out. And then Gil came to me and said he had embezzled a big sum from the brokers he works for and sunk it in United Traffic. He was frantic. This was only day before yesterday. As I said, I was under a great obligation to him. I promised to see uncle and try to get a loan to help him out. I meant to do it tonightâand this afternoonâand uncle's dead. I had an appointment to see Gil at Brockton. He'sâyou saw what condition he's in. They're onto him and he's laying low. I don't know what to doâI'm all broken up about Uncle Carson and I can't think anyway. I thought maybe I'd see Mr. Mawson in the morning.”

The young man finished and the detective began to ply him with questions. All of them he answered readily and consistently. About them was the soft silence of the countryside, broken only by their voices and the rhythmic pat of their feet on the macadam as they swung along side by side; the moon was dropping to the horizon now, and there was a new ghostliness in the long narrow shadows of the trees as they stretched into the fields and moved their lazy fingers to and fro over the quiet grass. The two men became silent, walking more swiftly; an abrupt question now and then, and its answer, was all that was heard for half an hour.

“The best thing you can do is to drop this Gil Warner entirely,” Rankin observed as they came within sight of the gate of Greenlawn. “Obligation is one thing and common sense is another. He's a crook anyway, and the more you do the more you'll have to do. You say you think he's not been in this neighborhood before. I'll find out about that. He may knowâ”

The detective stopped short.

“By Jove, I'd forgotten!” he exclaimed after a moment.

Harry turned inquiring eyes on him.

“There was a man following me,” Rankin explained. “He came out of the Greenlawn gate and followed us all the way to Brockton. I saw him there in a doorway. In the excitement I forgot all about it.”

“He came out of Greenlawn?”

“Yes. Not far behind me. He followed all the way.” Half involuntarily the detective wheeled and looked back down the road. The next instant he grasped Harry by the arm.

“There he is now!” he cried.

CHAPTERÂ V

H

arry turned and gazed back down the road.

“Where? I don't see anyone.”

“No. Not now. He jumped into the shadowâthat clump of trees on the right.”

“But who can it be?”

“I don't know.” The detective stood peering intently toward the clump of trees two hundred yards away. “It looks as though you'd got mixed up in a dirtier piece of business than you bargained for.”

“Whatâyou don't mean Uncleâ”

Rankin interrupted him:

“Ah, there he is!”

With the words the detective was off toward the trees with a bound, and without an instant's hesitation Harry was at his heels. Back down the road they raced at the top of their speed; and when they had traversed half the distance, in the dim glow of the waning moonlight they saw a figure dart suddenly out of the shadow across the road, scramble over the fence and start at a dead run across the fields like a startled rabbit. Rankin swerved aside, squeezed between the wires almost without halting and took after him. Harry, not far behind, was calling as he ran:

“Cut across! He's making for the woods!”

Rankin had already seen and was straining every muscle to intercept the maneuver, but Harry, with his youthful athletic stride, soon passed him. The man ahead bounded frantically across the furrows without looking back; his goal was evidently the fringe of woods bordering the river some five hundred yards from the road, and the advantage was his, as the two converged at a point half a mile down. Rankin, seeing himself outdistanced by Harry anyway, took it easier, as his injured shoulder was causing him considerable pain; then, seeing their quarry finally reach the edge of the woods and disappear, he pushed forward again. When at length he reached the spot he could see nothing, for the waning moonlight stopped at the barrier of the thick foliage and left all in darkness. Young Adams, too, had disappeared.

From the woods, some distance within, came the sound of rushing footsteps and rustling branches, and the detective pushed forward in that direction, calling meanwhile:

“Harry! Harry! Where are you?”

An answering shout came:

“Here! This way!”

Rankin went on, stumbling over hollows and fallen trees and scratching his face and hands on the low-hanging branches. The sounds ahead of him grew fainter, then suddenly swerved to the left and seemed to be approaching. Here in the midst of the woods the night was black, though now and then, through the interstices of the leaves, could be seen the faint shimmer of the last rays of the moon on the surface of the nearby river.

“Where are you, Rankin?”

The detective answered and thrust his way blindly toward the voice. The sounds of commotion had ceased. Two minutes later he came suddenly upon Harry at the edge of a small clearing.

“Is it you, Harry? Have you lost him?”

The young man nodded. “Keep still a minute.”

They stood there motionless, listening, enveloped in darkness and silence. The woods were still as the tomb; there was not so much as the sound of a rustling leaf; from a distance there came faintly on the air the murmur of the river in the shallows half a mile below.

“He got through the thicket to the bank,” said Harry at length, “and started downstream. Then he dived into the underbrush again and I couldn't tell which way he went. I thought I heard him again, but it was you. He's lying low not far from us right now.”

They listened another while, but no sound came.

“No use; he's given us the slip,” the detective finally observed.

They turned reluctantly and made their way back through the woods. A match showed Rankin the face of his watch; twenty-five minutes past two. When they got to the open they found that in the short interval of their search the moon had dropped below the edge of the hills to the east, leaving the sky light and the earth dark. Tramping across the stubble, they crossed over the fence into the road, and five minutes later were at Greenlawn.

“You're sure the fellow came out of here?” Harry was asking as they turned in at the gate.

Rankin replied that he was.

“That's funny. I thought it might have been Fred, but of course he wouldn't have run. I can't understand it.”

A dim light could be seen in one of the upper windows of the house, in the room where Dr. Wortley was keeping his lonely vigil with the earthly remains of the dead Colonel.

All within the house was quiet. Rankin and Harry mounted the stairs together, without speaking; after the excitement of the past four hours the gloom of the house of death had dropped its heavy mantle over them at the threshold. At the first landing they parted, Harry to mount another flight and the detective to continue down the hall to his own room at the further end.

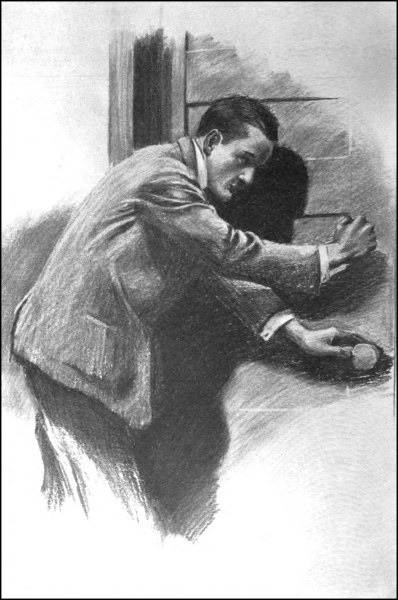

There he halted with a sudden appearance of alertness. He heard Harry's footsteps traversing the hall above, and the soft opening and closing of a door. Then, instead of entering his room, the detective stepped noiselessly back down the hall and stopped before a door near the stair landing. He stood there listening intently for a full minute, then all at once raised his hand and rapped softly on the panel. When a second knock brought no response he noiselessly turned the knob and entered.

He stood there listening intently for a full minute, then all at once raised his hand and rapped softly on the panel.

The room was pitch dark. Rankin stood motionless just inside the door, without having closed it, straining his ear. When the utter silence had convinced him that the room was unoccupied he moved to the electric switch and turned on the light. One quick glance at the bed showed him that it had not been slept in, and with a gleam of satisfaction in his eyes he turned the light off again and left the room.

He stood hesitating for a moment at the top of the stairs, then turned down the hall to the door of his own room, and entered. The first thing he did after turning on the electricity was to take off his coat and shirt and have a look at the injured shoulder. An examination convinced him that it was nothing worse than a painful bruise. His movements were slow and mechanical, like a man lost in thought; and at length, with his hand stilt moving slowly back and forth over the bruised shoulder, he stood and stared fixedly at nothing with wrinkled brow.

Finally he pulled himself up. “Yes,” he muttered to himself, “but how the devil did he do it?”

Then, instead of undressing for bedâthough it was nearly three in the morning and he had had no sleepâhe turned with sudden decision and put his shirt back on, and his coat. A snap of the switch, and the room was in darkness. Placing a chair just inside the threshold (he had left the door open), he sat down to wait.