The Last Gun (34 page)

Authors: Tom Diaz

The very next day, Seattle was hit by yet another all-American shooting rampage. This mass murder was at a “quirky Seattle hangout,” a coffee shop and bar known for its “eclectic music and friendly vibe.”

2

The latest murders struck at Seattle's historic association with popular music. Ray Charles played at jazz clubs and made his first recording in Seattle. Jimi Hendrix, a Seattle native, got his start there. Decades later, the grunge era of the 1990s launched Nirvana and other bands.

3

The

New York Times

noted in 2010 that “a growing number of young musicians have been focused on building an autonomous scene, something distinctive and homegrown.” One of these young musicians' venues was Café Racer, “distinctly postgrunge, with its scuffed floor and mismatched furniture, its thrift-store paintings on boldly colored walls.”

4

The cafe is also the “Official Bad Art Museum of Art (OBAMA)” where one can “gaze in wonder at the astounding paint-by-number and black velvet paintings.”

5

The whimsy ended just before eleven

A

.

M

., Wednesday, May 30, 2012, when Ian L. Stawicki, holder of a concealed-carry permit,

walked in. Stawicki, forty, had been thrown out of Café Racer previously and banned because of his “loud, bizarre behavior.”

6

This erratic behaviorâthe hallmark of all too many of America's concealed-carry killersâwas familiar to Stawicki's family. His father said Ian had suffered from mental illness for years and his behavior had gotten “exponentially” more erratic. He claimed his son enlisted in the U.S. Army after high school but lasted only about a year before getting an honorable discharge.

7

(An army spokesperson said it had no record of Stawicki's having served.

8

) In any event, the family failed to convince Ian to seek help. Those who knew Stawicki said his life's history was “dotted with clues, including failures, social rejection, episodes of apparent delusions, spasms of violence and a strong interest in guns.”

9

None of this stopped Stawicki from getting his “shall issue” concealed-weapons permits from Seattle and Kittitas County

10

Nor did it prevent him from legally buying three 45 caliber and three 9mm semiautomatic pistols.

11

The familiar combination of a mentally unstable person legally carrying concealed handguns had its predictable result. Sixty-three seconds after Stawickiâwith two 45 caliber pistols in his pocketsâwalked into Café Racer and was refused service, he had shot four people to death and critically wounded another. Stawicki paused to steal a “bowler style” hat from one of his victims, then left. By 11:30

A

.

M

., he had confronted a businesswoman in a parking lot, shot her to death, and fled in her Mercedes-Benz SUV. He gave “the finger” to bystanders coming to her aid.

12

Police cornered Stawicki at around four

P

.

M

. He knelt on the sidewalk and shot himself fatally in the head.

13

The familiar public ritual commenced. “The city is stunned and seeking to make sense of it,” Mayor Mike McGinn said. “I think we have to start by acknowledging the tremendous amount of grief that's out there from the families and friends of the victims.”

14

Yet one of the purposes of this book is to ask the uncomfortable question: How are rituals of community healing, however

heartfelt, going to stop the violence with which the gun industry is polluting America? How are makeshift memorials of candles and teddy bears going to stem the flood of militarized killing machinesâassault weapons and high-capacity semiautomatic pistolsâthat abound in every community in America?

The sad but self-evident truth is that the fleeting ritual embrace of public sorrow is not action. At best, these moments of public ritual give the image-hungry media a few seconds of self-conscious sentimentality, and they give policy makers safe platforms to strike “caring” postures. Memorial events are tough-question-free zones. Eventually the cameras leave, the plastic flowers fade, the stuffed toys rot. And in the end, nothing has changed.

At worst, these weepy rituals play into the hands of the gun industry and its lobby. After major shootings, the NRA, the gun industry, and their cohorts suffocate any discussion of effective policies to stop gun violence. They piously argue that “now is the time to mourn.” Their self-righteous surrogates pretend that it is disrespectful to discuss gun-violence prevention while families and survivors are grievingâregardless of the fact that it is often fellow victims and survivors from prior attacks who make such demands. No one in his or her right mind would dream of making such a foolish argument in the wake of the crash of a passenger jet. Or after a terrorist attack.

The blizzard of gun violence documented in this book is not a “gun safety” problem. Nor is it a problem of legal versus illegal guns. It is a gun problem. It is the direct and inevitable consequence of the gun industry's cynical marketing, the proliferation of lethal firepower, and the waves of relaxed state lawsâconcealed carry, shoot first, shoot anywhere, shoot cops, just shoot, shoot, shootâthat the gun industry's handmaiden, the NRA, has inflicted on the country to promote new markets for the industry.

How can it be that Americans tolerate this relentless slaughter, when they have willingly spent trillions of dollars and surrendered their dearest constitutional rights to protect themselves

against the comparatively minuscule threat of terrorist attack? One explanation might be that Americans simply don't care about gun violence or its victimsâuntil it strikes them, or their families, or their neighbors, or their co-workers, or the people they worship with, or the artists they create with or listen to. In truth, some clearly do not care. Hypnotized by sepia-tinted fables of “gun rights” and socially impaired by their lack of empathy, they believe that no sacrifice is too great for others to bear so that they can enjoy unbridled access to their deadly toys, their lethal security blankets, and their pretended defense of liberty. The pro-gun writer and advocate Dave Workman, for example, “a loyal foot soldier in the pro-gun publishing and lobbying empire of convicted felon Alan Gottlieb,”

15

uttered an incredibly thick-witted explanation to the local NPR affiliate in Seattle following the Café Racer shooting. Nothing can be done, Workman argued, because the rest of us must respect the choices of gun-toting misfits like Ian Stawicki. “We can't treat him like a child, he's got his own life to live and he can make his own mistakes no matter how horrific those mistakes turn out to be.”

16

But most Americans do care about gun violence. They want change. What they lack first is information about its true dimensions and causes. The media whiteout and the gun industry lock-down of data leave Americans so poorly informed about how common and widespread gun violence is that they are surprised when it strikes them and often write it off to mere chance. They ignore the contradictions inherent in their own observations about the more frequent types of gun violence, such as how the previously law-abiding shooter “seemed like such a nice person, we would never have thought he would do such a thing,” or “things like this just don't happen in our community.”

From policy makers, the press, and self-appointed experts, we are often presented with statements and plans of action that reinforce common misperceptions about gun violence instead of challenging them. The result is that America lacks a clear national plan of action to significantly reduce gun violence. The essential

elements of such a plan are fact-based public health action programs that have been proven effective over decades. “In 1900 the average life expectancy of Americans was 47 years,” David Hemenway, director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center and the Youth Violence Prevention Center, wrote in his 2009 book about the public health approach. “Today it is 78 years. Most of this improvement in health has been due to public health measures rather than medical advances.” Hemenway explained that “the concern of public health is to improve the health of societies,” and its focus is “not on cure, but on prevention.”

17

Motor vehicle safetyâwhich most Americans now take for grantedâis a prime example of fact-based public health action. Between 1966 and 2000, the combined efforts of government and advocacy organizations reduced the rate of motor vehicle death per 100,000 population by 43 percent. This represents a 72 percent decrease in deaths per vehicle miles traveled.

18

And as a direct result of these public health measures, motor vehicle death and injuries continue to decline. In 2010, the number of fatalities in motor vehicle traffic crashes was 32,788âthe lowest level since 1949. This drop took place despite a significant increase in the number of miles Americans drove.

19

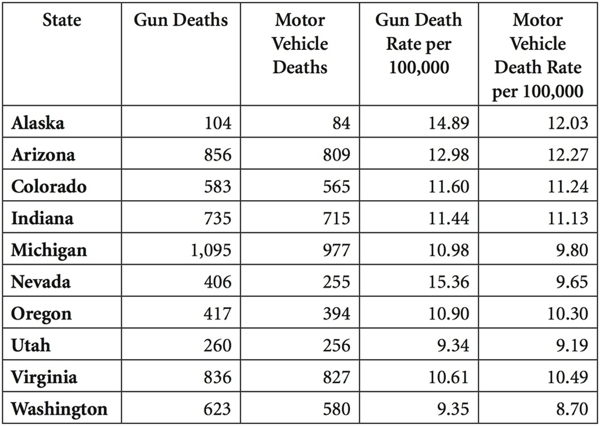

Yet as motor vehicle-related deaths have declined, firearm deaths have continued unabatedâthe direct result of the failure of policy makers to acknowledge and act on this ubiquitous public health problem. In shocking point of fact, gun fatalities exceeded motor vehicle fatalities in ten states in 2009. In that year, as

figure 11

shows, gun deaths outpaced motor vehicle deaths in Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Indiana, Michigan, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Virginia, and Washington.

20

What is the difference? It is that firearms are the last consumer product manufactured in the United States that is not subject to federal health and safety regulation. As Hemenway explained in another book, “The time Americans spend using their cars is orders of magnitudes greater than the time spent using their guns. It is probable that per hour of exposure, guns are far more dangerous. Moreover, we have lots of safety regulations concerning the manufacture of motor vehicles; there are virtually no safety regulations for domestic firearms manufacture.”

21

Examples of federal agencies and the products for which they are responsible include: Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), household products (except for guns and ammunition); Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), pesticides and toxic chemicals; Food and Drug Administration (FDA), drugs (including tobacco) and medical devices; and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), motor vehicles.

Figure 11. Firearm Deaths Exceeded Motor Vehicle Deaths in Ten States in 2009

In 2009 there were 31,236 gun deaths nationwide for a rate of 10.19 per 100,000 and 36,361 motor vehicle deaths (both occupant and pedestrian) nationwide for a rate of 11.87 per 100,000 (both totals include data only for the fifty states). WISQARS database, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Before the advent of the public health approach, the focus in motor vehicle safety was on changing the behavior of the “bad driver” or “the nut behind the wheel,” and it had limited results.

22

The establishment of NHTSA in 1966 marked a distinct change. It was part of a sustained decades-long public health effort to develop and implement a series of injury-prevention initiatives that work and have saved countless lives. These public health initiatives made changes in both vehicle and highway design. Vehicles incorporated such new safety features as better headlights and brakes, head rests, energy-absorbing steering wheels, shatter-resistant windshields, safety belts, and air bags. Roads that vehicles travel have been improved by more effective marking of curves, use of breakaway signs and utility poles, better lighting, barriers separating oncoming traffic lanes, crash cushions at bridge abutments, and guardrails.

23

Experts also cite the increase in the use of seat belts, beginning in the mid-1980s as states enacted belt-use laws, and a reduction in alcohol-impaired driving as Mothers Against Drunk Driving and other organizations changed the public's perception of the problem and laws were enacted to increase the likelihood that intoxicated drivers would be punished. Graduated licensing laws are credited with helping to reduce the number of teen drivers crashing on our nation's roadways.

24

It is extremely important to note that the creation of NHTSA's comprehensive national data system was a vital part of this success, because it “enabled scientists to determine the main factors affecting road safety and which public policies were and were not effective.”

25

Pioneers in vehicle safety “insisted that the injury field be based less on opinion and more on science.”

26