The Latte Rebellion (4 page)

Read The Latte Rebellion Online

Authors: Sarah Jamila Stevenson

Tags: #young adult, #teen fiction, #fiction, #teen, #teenager, #multicultural, #diversity, #ethnic, #drama, #coming-of-age novel

Even though the itchy sweat under my hairline was trying to tell me differently.

“Order,” the disciplinary hearing officer demanded one last time, and the crowd complied. All fifty-plus of them. Of course, that number didn’t include those on the dais; the hearing panel sat behind a long, semicircular desk, slightly above the audience and directly facing

me

. I could see Vice Principal Malone standing to one side, gazing at me with an unreadable expression, and I clenched my muscles so I wouldn’t fidget nervously. I stared over at the California flag in the corner of the room so I wouldn’t have to look anyone in the eye.

“We will begin by reading the charges against Ms. Jamison, and then proceed to examine the evidence of her violations of school and district policy. Witness testimony will follow. After the hearing, the panel will determine whether or not to recommend expulsion to the school board.” The hearing officer sighed, as if the entire proceedings bored him beyond belief. As if this was nothing but a routine disciplinary hearing. For him, maybe it was.

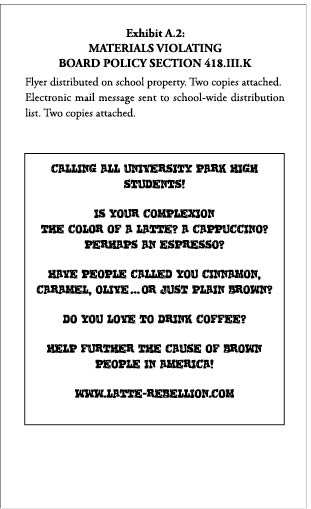

“Charge number one: Willfully and repeatedly violating School District Policy 418.III.K—by intentionally harassing a group of students, creating substantial disorder, and causing a hostile educational environment. This was done through the distribution of inflammatory materials on school property.

“Charge number two: Violating School District Policy 418.III.M—by repeatedly disrupting school activities and defying explicit school policy regarding unsanctioned activities.

“Charge number three: Violating School District Policy 418.III.N—by engaging in what was construed by some as a terrorist threat.”

Even though I was ready for it, even though I’d known that the T-word was going to come up sooner or later, my stomach sank to the very bottom of my shoes.

This was it. My success or failure in this room today would determine whether my thus-far stellar academic life would continue on with relative normalcy … or whether it was well and truly over, and my lifelong career as burger flipper was about to begin.

To:

From: Latte Rebellion

Re: A Call to Arms, or All Hands on Mugs

Dear Friends,

Please read this missive carefully. We need your help. If you got this message, you may already be playing a key role in the Latte Rebellion. You may be a relative, a friend, a Sympathizer, or even an Organizer.

What we need from you is simple. In order for the Latte Rebellion to achieve its goal of spreading the word around the English-speaking world, consuming coffee at every turn, we must raise the necessary funds. Towards this end we ask you to (A) buy our T-shirt, and (B) forward this information to everyone you know and ask them to buy a T-shirt.

Not sure you want to be a part of the Latte Rebellion? Visit our website for more information:

www.latte-rebellion.com

Incidentally, this is also where you can purchase the T-shirt. The Movement Thanks You!

Yours in latte-ness,

Agent Alpha and Captain Charlie

P.S. This is not a joke. We really are selling shirts.

Publicizing the Rebellion should have been easy. If you looked at our written plans, it

was

easy.

But thanks to my parents—and my Hindi-speaking, sari-wearing Indian grandmother, who lived several hours south of us in Bakersfield—our plans suffered a slight delay.

“I hope you finished vacuuming your room,” my mother said on Monday night, rubbing a hand tiredly through her short-cropped dark hair. We were in the living room watching one of my father’s favorite movies, a documentary called

Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room

. Dad was absorbed, as usual, in the sordid white-collar drama of a huge corporation imploding; meanwhile, I was taking mental notes on what

not

to do if I was ever on the board of a multi-million-dollar company, and lamenting the fact that other people’s fathers (normal ones) made their kids watch

Star Wars

or James Bond movies, a fate I would happily endure given the choice

.

Not that anybody gave me one.

“I need you to work on the guest room before Nani comes tomorrow,” my mom continued doggedly. “I’m giving parent-teacher conferences and won’t be able to leave until four.”

“Nani’s coming

tomorrow

?” I stared unseeingly at the TV, frustrated. “But it’s the middle of the week.” My parents were very into “quality family time,” so it wouldn’t be easy to extricate myself in order to hang out with Carey and start our publicity blitz.

Crap, crap, crap.

“Your Nani misses you,” my mother said, trying a different strategy—one involving guilt and wheedling. “She said she’s looking forward to spending some time with you, helping you practice your Hindi. And she wants to teach you how to cook your favorite chicken biryani.”

I groaned. My dad looked up briefly from the TV. “She really wants to teach you about your culture, Asha. I wish I’d had that at your age. Your Grandma Bee didn’t even

try

to teach me Spanish.” He gave an ironic laugh. “If only she’d known how useful it would be in the business world.”

Useful. Har. My knowledge of Hindi would get me about as far as a five-year-old looking for a bathroom. And my parents had clearly forgotten Nani’s disastrous attempt to teach me traditional dances when I was in junior high, which ended abruptly when I was trying the

dandia raas

for the umpteenth time and one of my sticks went flying and broke a vase.

Still, Nani insisted that it was in my blood. “

Arré

, it is your culture,” she’d say mournfully, at least once a visit. But it wasn’t that simple. Indian culture—well, it didn’t feel like it was

my

culture, not any more or less than my dad’s Irish and Mexican heritage. I was just me. Whatever that was.

Incidentally, “whatever that was” turned out to be a more-than-apt way of describing the results of my sad attempt at chicken biryani, despite Nani hovering and issuing imperious instructions at every turn.

“

Nahi, nahi—

not like that! Let the onions get brown but don’t burn them,” she exclaimed, as I rushed to turn off the screeching smoke detector before we all went deaf. Meanwhile, Nani tucked the billowing, bright-magenta folds of her sari safely out of the way and rescued my slightly scorched onions, still sizzling in our biggest pot. I heaved a sigh and opened the kitchen windows to let out the smoky onion smell.

“Okay, Asha

beti

, not to worry,” Nani said, rummaging in the back of the cupboard and pulling out an array of spices only my mother ever used. “It won’t matter. Next step: we finish the gravy, all right?” She turned to me, an expression of concern on her plump brown face.

“Fine,” I said, swallowing my pride in the face of her obvious—and understandable—fear that I’d never be able to fend for myself in the kitchen. I picked up an unlabeled jar of brown spice powder. “So, a teaspoon of cinnamon, right?”

Nani

tsk

ed. “An inch of cinnamon stick.” She pointed at the jar I was holding. “That’s the garam masala. Three-quarters of a teaspoon. Remember?”

I set the jar down with a thunk. This was hopeless. It didn’t matter if it was my culture, it didn’t matter if Nani measured everything out for me and wrote it all down in neat cursive on a sheet of scrap paper from the printer. I was not innately able to channel my Indian heritage at will, any more than I could become an Iron Chef after a handful of cooking lessons.

Yet here I was, stuck in the kitchen with a half-burnt pot of onions, an assortment of indistinguishable spices in varying shades of brown, and a grandmother attempting to hide her despair at my clear lack of culinary talent.

I really needed to get out of here.

“Mom,” I said over dinner a few evenings later, making sure I’d finished every last grain of rice and mopped up all of my lamb korma with a piece of naan, even though I was full to bursting and did not need the extra carbs. “I have to ask you something.”

She eyed my clean plate suspiciously.

“Can I go out with Carey tonight? We’re supposed to go to a workshop at school on college application essays.” I crossed my fingers under the kitchen table. Carey, of course, was already done with her essay. As for the workshop, I’d been planning to go, but our current project took precedence.

“College essays?” Mom glanced at Dad, who gave a quick nod. “I suppose it’s fine, if you’re back by nine thirty.”

I let out a silent, relieved breath.

“Such a good, studious girl,” Nani said, patting me on the arm and beaming.

Her familiar scent of curry powder, sandalwood soap, and mothballs wafted over me as she hugged me goodbye half an hour later. I tried not to flinch guiltily.

When I got to Carey’s house, she was in the middle of cleaning jam off her brother Davey’s head with a damp dishtowel.

“I’m sorry, Ash,” she said, rolling her eyes. “I just need a second. My dad’s in the shower and of course

this

happened. Could you just go make sure Roddy’s still watching cartoons in the living room?”

“Poor you,” I said, peering around the corner to where Roddy was sitting raptly in front of some anime show, watching ginormous robots bent on annihilating each other. “He’s fine. He’s just enjoying some wanton cartoon violence.”

“Great. Now I know why he was trying to build a giant homicidal robot out of Legos.” Carey sounded exhausted. With three boys under the age of twelve, the Wong household was always a few incidents short of complete chaos.

“You really do need to move away for college, don’t you?” I leaned against the counter next to the sink, where Carey was washing her hands. Davey was now jam-free, sitting in his high chair and happily shoving crackers into his mouth.

“No freaking kidding. Mom is still on my case about going to U-NorCal so I can live at home. Can you believe it?” She shook her head. The University of Northern California was conveniently located here in town, but it wasn’t an option for me, either. I had my eye on bigger prizes—namely Stanford, Harvard, UC Berkeley, and the über-selective Robbins College, also in Berkeley.

I hadn’t mentioned it to Carey yet, but it was a recurring daydream of mine that she and I would both get into schools in Berkeley and move into an apartment together. A sibling-free, parent-free, grandmother-free, Roger-Yee-free apartment. With an ample supply of frozen enchiladas—something I actually

could

cook.

Over the burble of the dishwasher, Carey’s mom shouted something about being home on time so she could finish her homework. Carey sighed.

“So,” I said, “your car or mine?”

“My imaginary Lamborghini’s in the shop,” she said. Not for the first time, I felt relieved to be an only child—because I had my own car. It was ancient, it was slow, and it was surely not pretty—hence its nickname, the Geezer—but it was all mine. We piled in and immediately cranked open the windows to let in the cool evening air.

“What’s first on our list?” I asked Carey, Keeper of the Master Plan. She shuffled a few papers.

“Um … Mocha Loco. Tenth Street and Oak.”

We drove in silence for a few minutes. The sun was almost completely down, and the streetlights were already on. As we got close to the university campus, the sidewalks grew more clogged with students. I could smell garlic from the Italian deli wafting on the breeze, and the faint aroma of eucalyptus leaves.

“Are you nervous, Asha? You’re unusually quiet,” Carey said.

“Nope, not even a little. This is going to be

amazing

.” I turned onto Oak and started looking for a parking spot. “I can’t stop thinking about how it’s going to feel to be

somewhere else

next summer … I mean, think about it. No parents, no school … just relaxing … shopping …”

“… ogling tasty guys,” Carey put in.

I grinned. “And getting them to take us out for coffee.”

Yeah, we were a little obsessed.

At the last minute, a car pulled out right in front of Mocha Loco, and I swerved into the space.

Here we go,

I thought to myself as we got out of the car, making sure we had our flyers as well as pushpins and scotch tape for any contingency.

The green plastic patio tables were full of people studying. None of them paid any attention to us as we wound our way through and into the café. Inside, the tables were packed with more college students and professor types, buried in fat textbooks or having deep philosophical discussions. I felt … out of place. My excitement dimmed a little as we squeezed past tables and chairs, and I was convinced that I was going to bump into somebody or knock someone’s coffee over with my butt. My

round

butt.

There was a two-piece band in one corner playing folk guitar ballads, and everyone was conversing at an even louder volume as a result. The hubbub of voices was giving me a headache, and I could feel nervous sweat prickling at the back of my neck.

“Now what do we do?” I stared at the throng of people and finally located a bulletin board—already crammed with flyers—on a stand next to the cash register.

“No problem; we can handle this,” Carey said, grabbing one of the flyers out of my hand and marching up to the cash register. I trailed behind, not wanting to get trampled by caffeine-crazed college students.

“Here’s the plan,” Carey said in a stage whisper. She pulled on my wrist and I leaned toward her. “You buy a coffee from that guy. Just act normal. I’ll ask him about the flyer.” This was the upside of Carey’s control-freakishness: she always had a Plan B. I’d seen it in action on the soccer field, as she shouted strategic maneuvers out to her teammates, but it never ceased to amaze me. I was more of an idea person, a motivator. I was no strategist.

I went up to the counter, trying to project more confidence than I was feeling. The guy behind the register was kind of cute, with dyed-black hair, dark eyes, a nice tan, and an eyebrow ring.

Make that

very

cute.

I could see a tattoo of some kind of Chinese character on his upper arm, disappearing under his T-shirt sleeve. Definitely a potential Rebellion Sympathizer. I gave Carey’s arm a little squeeze and took a deep breath.

“Can I get a large iced latte, please?” It came out a lot quieter than I’d planned, more like a whispery squeak than a confident request for coffee.

“What was that?”

Carey elbowed me. I tried again.

“Um, an iced latte?” I smiled and tried to make eye contact.

“Whipped cream?” the guy asked in a bored voice.

Leonard

, his name tag read.

“No thanks, Leonard.” I elbowed Carey.

“Excuse me.” Carey looked up at him—he was pretty tall—and put on her cutest smile, blinking at him a little. “We were wondering if we could put a flyer for our …

um … organization on your bulletin board?”

Carey has really striking hazel eyes, which was why Jonathan Burmeister wouldn’t leave her alone. And before that, Kendall DeSoto, Eddie Green, and about twenty zillion others. I could see what was coming. I wasn’t blind.

“Sure, go ahead,” Leonard said. “It’s a student organization, right? Not a corporate thing?”

“Uh—”

I nudged Carey again.

“Yes,” she said stiffly.

It wasn’t a lie. We were students. We were organized. Kind of.

“I’ll have to have the manager take a look at it, but go ahead and put it up for now.” He smiled at Carey, and handed me my latte without even looking at me. Of course. Like I even had a chance. Let’s just say that, standing next to Carey, I was not the one you’d notice first.

Carey pinned up the flyer with a stray thumbtack and then turned back toward the counter, flipping back her short hair coyly. “So what’s the tattoo of?” she asked with a sly smile. “I don’t read any Chinese.”

And it drives her dad crazy

, I considered adding, but I refrained from doing so.

“It’s the symbol for luck, combined with a horse, for year of the horse. My birth year.” He leaned on the counter with one elbow, the better to show off his ink.