The life of Queen Henrietta Maria

Read The life of Queen Henrietta Maria Online

Authors: Ida A. (Ida Ashworth) Taylor

Tags: #Henrietta Maria, Queen, consort of Charles I, King of England, 1609-1669

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

PREFATORY NOTE

AN attempt is made in the present volume to give an account of the life of Henrietta Maria de Bourbon, the general history of the time being dealt with only so far as is necessary for that purpose.

It is somewhat singular, taking into account the important part she has been charged with playing in the English " troubles" of the seventeenth century, that so little has been written with direct reference to the wife of Charles I. Since the life published at the time of the Restoration—" so sillily writ" that Pepys and his wife could do nothing but laugh at it—there have been no more than a few brief memoirs, in French and English, of which Carlo Cotolendi's is the fullest ; followed in the last century by the biography included in Miss Strickland's Lives of the Queens of England, and the French life by the Comte de Baillon, mainly based upon the last.

On the other hand, materials for a biography are unusually ample. Mrs. Everett-Green expended infinite labour on deciphering, translating, and editing those of Henrietta's letters to Charles I. which have been preserved ; whilst these and others have been printed by M. de Baillon in the original French. A work of

hardly less importance was performed by M. Ferrero in the publication of the correspondence she carried on during most of her married life with her sister, Christine, Duchess of Savoy.

Besides the material furnished by Henrietta's letters, collections of state papers and other contemporary documents, as well as the copious memoirs of the day, French and English, are full of facts, incidents, and allusions making it possible to form a very clear conception of the woman who was loved by Charles I., as some have thought, to his undoing ; of whom Charles II., notwithstanding the friction of earlier years, wrote that never any children had so good a mother ; and who was declared by his brother James, in language more stilted, to excel in " all the good qualities of a good wife, a good mother, and a good Christian."

Such was the testimony of her sons. If her husband and her children loved her, the world did not ; and the bitterness of the hatred she excited is not without its uses, positive and negative, in enabling a biographer to arrive at a just estimate of her character. The importance attaching to a large body of contemporary opinion cannot be overlooked. Condemnation of declared opponents of the royalist cause must indeed be accepted, if accepted at all, with reserve ; but some of the most loyal adherents of her husband and son were amongst the severest of her critics ; nor did they, especially in later days, practise any economy of truth with regard to her failings. Allowing for the natural jealousies existing between the several factions into which the royalist party was divided, the witness of these men must not be disregarded. On the other hand, whilst allowing it due weight, the very candour of their blame

tends to exonerate the object of their dislike from faults of which they did not accuse her. Judging her even out of the mouth of her enemies, the evidence against her points rather to errors of the understanding than of the will; to rashness, unwisdom, and prejudice rather than to any more serious moral delinquencies. The distinction, it is true, may have been of little consequence, as affecting the damage inflicted on the cause with which she was identified, and a worse woman might have made a better counsellor. But with regard to Henrietta herself it is a different matter.

A short appendix, at the end of the book, sums up the scanty evidence available on the question of the Queen's marriage with Henry Jermyn. A list of the principal authorities consulted is also appended. I desire to express in especial my obligations to Mr. Gardiner's detailed history of the period and to the great assistance it has afforded me.

I. A. T.

CHAPTER IV 1625—1626

PAGE

Popular discontent—Charles and Buckingham—Henrietta's refusal to be crowned—A fresh quarrel—Buckingham attacked by Parliament—The Queen's household dismissed—Henrietta's loneliness—Bassompierre's mission—His success—Buckingham forbidden to go to Paris—Preparations for war—The Rochelle expedition—Its failure—Improvement in the relations of King and Queen 77

CHAPTER V 1627—1630

The Duke's return—Harmony in the royal household—The new Parliament—Petition of Right—Wentworth's change of front— The Duke murdered—The Queen's future position—Birth and death of her first child—Domestic happiness—Ecclesiastical arrangements at court—Birth of Charles II.—Henrietta's description of him 95

CHAPTER VI 1630—1633

Exile of Marie de Medicis—Henrietta's growing influence—Charles still independent of it—His foreign policy—The Queen's hostility to Spain—Charles' refusal to receive her mother—The Chevalier de Jars—Letters of Henrietta's and Lord Holland's opened— Quarrels at court—Jermyn's misconduct—Birth of the Princess Royal—Charles crowned in Edinburgh—Birth of James II.— Letter from Wentworth . 118

CHAPTER VII 1630—1634

The lull before the storm—The court—Henrietta—Charles—The Lord Treasurer, Weston — Laud — Wentworth — Hamilton — Holland—Lord and Lady Carlisle—Other courtiers—The Queen's Pastoral—Earl of Newcastle—His instructions to the Prince of Wales—Letters from the Queen and Prince—Henrietta and her sister 132

CHAPTER VIII 1634—1637

PAGE

Henrietta not concerned in Charles' foreign or home policy—Money difficulties—Puritan distrust—Panzani's mission—Panzani's relations with court and ministers—Hopeful reports sent to Rome—Conversions—Panzani and the Queen—Charles friendly —Con and Hamilton appointed agents to Urban and Henrietta— The Prince Palatine and Prince Rupert visit England—Royal visit to Oxford—Popular discontent—Departure of the Princes . 153

CHAPTER IX 1637—1638

The Pope's envoy, Con—Conversions at court—Laud's proclamation— Scottish affairs—Hampden's trial—Decision of the judges—Court gossip—Rivalry of Northumberland and Holland—Wentworth on Holland—Wentworth's own aims—Relations with Henrietta— The Scottish Covenant inaugurated—Arrival in England of Marie de Medicis—Her interview with de Bellievre . . .175

CHAPTER X 1639—1640

Wentworth's letter—Preparations for war—Need of money—Choice of officers—Wentworth and the Queen—Charles in the north— A treaty signed with the Scotch—Marie de Medicis and her son—Wentworth's growing influence—Becomes Earl of Strafford —Secretaryship conferred on Vane—Henrietta in opposition to Strafford—Rossetti papal agent in England—Departure of Duchesse de Chevreuse—The Short Parliament—Growing disaffection—Henrietta appeals to Rome—Failure of northern campaign 104

CHAPTER XI 1641

The Long Parliament—Henrietta's position—Strafford impeached— Death of Princess Anne—Suspicions of Parliament—Henrietta's endeavours to save Strafford—The Army Plot—Goring's treachery—Marriage of the Princess Royal—Stafford's execu-

tion—Attitude of the Houses—The Queen and Rossetti— Parliament interferes to prevent her leaving the country—Charles goes to Scotland—Marie de Medicis' departure . . . .216

CHAPTER XII 1641—1642

The Queen at Oatlands—Henrietta and Parliament—Rumoured plot —The Irish rising—Charles' return—His reception in London— Riots in London—The Remonstrance—Henrietta's unpacific attitude—Rumoured impeachment of the Queen—The five members—King and Queen leave London—Professions of the Prince of Orange—Digby's intercepted letter—The Queen takes the Princess to Holland 238

CHAPTER XIII 1642—1644

Henrietta at the Hague—Her labours—And letters—The royal standard set up—The Palatine Princes—The Queen in danger at sea—Letter from Charles—The Queen lands in England— Fired upon—Fairfax's offer of escort—Life with the troops—At York—The effects of her influence on Charles—Her impeachment in Parliament—Marches south—Joins the King . . . 259

CHAPTER XIV 1643—1644

Meeting of King and Queen—Jermyn—At Oxford—Dissensions in the Royalist party—Overtures from the Earls of Holland and Bedford — Holland's double treason — Henrietta's letters to Newcastle—Death of Falkland—French professions—D'Har-court's embassy—Solemn League and Covenant—Henrietta parts from the King—At Exeter—Birth of Henriette-Anne— Henrietta's letters to Charles—Her flight—Arrives in France . 286

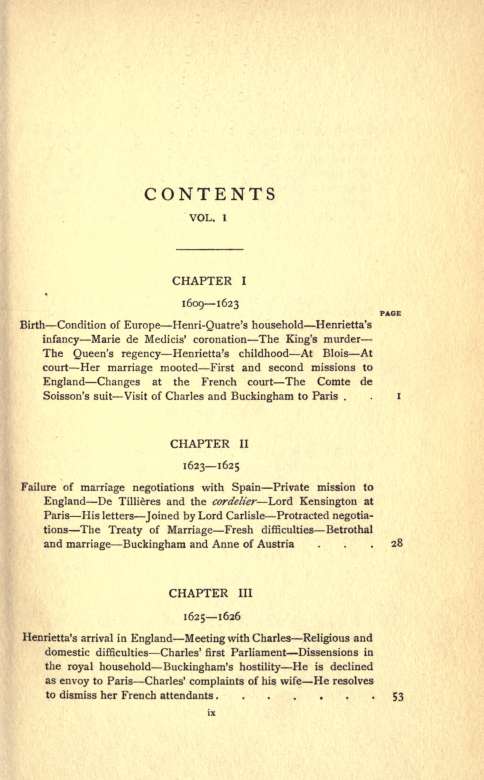

VOL. I

QUEEN HENRIETTA MARIA (Photogravure) . > . . . Frontispiect

Facing page

HENRIETTA MARIA AND HER SISTER l6

From a contemporary picture by an unknown painter.

JAMES HAY, EARL OF CARLISLE 36

From the picture by Van Dyck, by permission of Viscount Cobban.

GEORGE VILLIERS, FIRST DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM '5°

After the picture by Gerard Honthorst in the National Portrait Gallery.

CHARLES THE FIRST 80

From the painting by Van Dyck at Windsor Castle.

GEORGE VILLIERS, FIRST DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM (AFTER HIS ASSASSINATION

BY FELTON) 102

From the picture by Van Dyck, by permission of the Marquis of Northampton.

WILLIAM LAUD, ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY 138

After a copy of Van Dyck's picture in the National Portrait Gallery.

CHARLES II. AS PRINCE OF WALES 150

From the picture by Van Dyck at Windsor Castle.

CHARLES LEWIS, PRINCE PALATINE l66

From an engraving after Van Dyck's picture.

ALGERNON PERCY, EARL OF NORTHUMBERLAND 184

After a copy of Van Dyck's picture in the National Portrait Gallery.

MARY, PRINCESS OF ORANGE 208

After a picture by Van Dyck.

FIVE CHILDREN OF CHARLES I.. . , .' 312

After a copy of Van Dyck's picture in the National Portrait Gallery.

xiii

Facing pagt

WILLIAM OF NASSAU, PRINCE OF ORANGE 226

From a painting by Gerard Honthorst at Windsor Castle.

THOMAS WENTWORTH, FIRST EARL OF STRAFFORD 230

From the picture by Van Oyck, by permission of the Earl of Home.

ELIZABETH, QUEEN OF BOHEMIA 262

After the picture by Miereveldt in the National Portrait Gallery.

MARIE DE MEDICIS 272

From a contemporary engraving.

HENRT RICH, EARL OF HOLLAND 294

After the picture by Van Dyck.

CHAPTER I

1609—1623

Birth — Condition of Europe — Henri-Quatre's household — Henrietta's infancy—Marie de Medicis' coronation—The King's murder—The Queen's regency—Henrietta's childhood—At Blois—At Court—Her marriage mooted—First and second missions to England—Changes at the French Court—The Comte de Soisson's suit—Visit of Charles and Buckingham to Paris.

ON November 25th, 1609, Henriette Marie de Bourbon was born at the Louvre, the youngest daughter of Henri of Navarre and his Italian wife, Marie de Medicis—a child destined to become the wife of one king, the mother of two, and who, claiming in years to come the title of "la reine malheureuse," asserted her pre-eminence in sorrow.

The welcome she received was a cold one. The King was said to have declared that he would have given a hundred thousand crowns had the child been another son, whilst to the people a daughter represented only an additional burden on the national finances. No public rejoicings celebrated the event, nor was it announced with the customary salute of cannon.

The usual formalities were, however, duly observed, Henri himself, with his ministers of State and the VOL. i. I

princes of the blood, were present at the birth ; and the King, after the necessary recognition of the newborn infant as his own, handed her over in person to the care of the governess of the royal children, Madame de Monglat. This ceremony performed, he no doubt considered that his duty towards his unloved wife and her child had been discharged, and that he was at liberty to turn his attention elsewhere.

There was much in the condition of Europe at the moment to cause it to present an interesting study to eyes so keen and eager as those of Henrietta's father. The Evangelical Alliance and the Catholic League were standing over against one another, hostile forces, each seeking to enlist new allies, and awaiting an opportunity for settling their differences by an appeal to arms. To the ex-Huguenot King it was natural that the adherents of the new religion should look for support ; whilst the attitude of the court of Spain towards him was, as ever, irreconcilable in its enmity. An open breach could not be much longer deferred, and Henri was ready, if not anxious, to take his part in the fray. In spite of the policy of peace he had consistently pursued for ten years past, fighting was his natural occupation—almost his recreation ; and on the battlefield he was more at home than in a palace. For months he had been strenuously preparing for the contingency of a war, and actively engaged in raising money and collecting troops with a view to taking the field in person so soon as the right moment should arrive for striking a blow at the House of Austria. It was evident that that moment was approaching.

The internal affairs of France were meantime in a satisfactory condition. During the interval following the Peace of Vervins the financial condition of the country,

under the management of the Due de Sully, had been retrieved, the Crown debts paid, the revenue increased, and taxation diminished. Manufactures had been encouraged, commercial enterprise promoted, public works inaugurated. Both as soldier and statesman the King was in a position to look backwards with satisfaction, and onwards without alarm.

Coming to Henri's own household, there was less cause for congratulation. If he had been eminently successful in managing the affairs of France, the like success had not attended his domestic arrangements. The fault was largely his own. Greatness and littleness, weakness and strength, were blended in his character to a singular degree. He was a greater figure, says one of his biographers, seen from a distance than when regarded close at hand. If the criticism might apply to many, if not most, of the world's heroes, it was true in an unusual measure of Henri. His faults had brought their own retribution, and his domestic life was one of misery.

When the divorce obtained, after long- delay, from Rome had enabled him to contract a second marriage, Henri had reluctantly consented to make Marie de Medicis, niece of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, his wife. The union, dictated by political expediency, had proved as unhappy as might have been anticipated. The Queen —" une femme grande, grosse, avec des yeux ronds et fixes," to quote Michelet's description, " 1'air triste et dur, Espagnole de mise, Autrichienne d'aspect"—had wholly failed to win her husband's affection ; while she, for her part, was not a woman to accept with meekness the position forced upon her, or to forgive the insult she had been offered when, brought a bride to Paris, she had found herself compelled to live under the same

roof as the King's reigning mistress, the Marquise de Verneuil.

Nor had she been without even more serious causes of disquietude than her husband's infidelities. The promise of marriage obtained from him by the Marquise was held in some quarters to throw a doubt upon the validity of his union with herself, and to raise a question as to the legitimacy of the royal children. It was known that Madame de Verneuil had a son whom she called her Dauphin, nor can the Queen have been ignorant that the possibility of obtaining a second divorce had more than once presented itself to Henri's mind. Under these circumstances his Tuscan wife was not likely to forget her wrongs, or to allow herself to be softened by the graceful and charming letters addressed to her by the King, than whom no man was a greater master in the art of such compositions. It might be well to be told that, were it btem&ant to declare oneself in love with one's own wife, Henri could assure her that he was very much in that condition. But deeds, as well as protestations, would have been necessary to restore peace, and deeds were not forthcoming.

Political differences had widened the gulf opened by private dissensions. The year before Henrietta's birth a Spanish ambassador had arrived, charged with a proposal for the double marriage afterwards carried into effect, conditional on the King's abandonment of the Low Countries. The Queen had been eager to close with the offer, but Henri remained obdurate. Pledged by treaty to the enemies of Spain, he intended to continue true to his word. He attempted, however, to soften the Queen's resentment, and to restore some degree of harmony to their relations, by the suggestion, in February, 1609, of a domestic compromise. If Marie

would consent to dismiss her Italian favourite, Concini, and his low-born wife, the Queen's foster-sister, Henri, for his part, offered to give up all connection with any woman but herself. The terms of the proposed arrangement were not carried out. Concini and his wife remained at court, their influence over the Queen dominant; whilst Henri's manner of life continued unaltered.

His promise, had it been accepted, would scarcely have proved binding upon a man of his habits and temperament. Almost at the very time that his overtures of conciliation had been made, a fresh element of discord must have been supplied by the passion he had conceived for Mademoiselle de Montmorency, then barely sixteen, and who a few months later became the wife of his nephew, the Prince de Conde. When, four days after Henrietta's birth, Conde, taking the safe-guarding of his wife's honour into his own hands, fled with her into the dominions of the King's enemy, the Archduke Charles, Henri's rage and despair knew no bounds. As uncontrolled in his passions as a boy of twenty, it has been believed by some historians that the vehemence of his desire to regain possession of the fugitives was more instrumental in finally determining him upon taking the field than any arguments of state policy.

It is certain that preparations for war were pushed vigorously forward during the first months of Henrietta's infancy. In the meantime the latest addition to the royal nursery had probably vindicated, in her father's eyes, her right to existence. Henri was an affectionate father. His children, he once told Sully, were the prettiest in the world, adding that his happiest hours were spent in playing with them ; and the journal of the Dauphin's domestic physician, Jean Heroard,