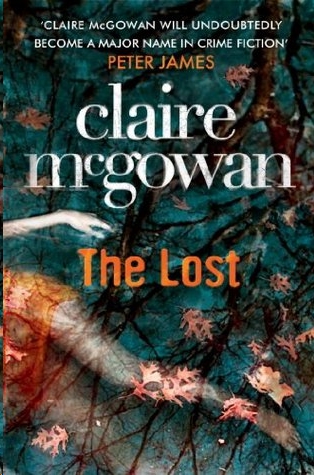

The Lost

Claire McGowan

The Lost

Copyright © 2013 Claire McGowan

The right of Claire McGowan to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2013

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN : 978 0 7553 8639 0

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Contents

Not everyone who’s missing is lost

When two teenage girls go missing along the Irish border, forensic psychologist Paula Maguire has to return to the home town she left years before. Swirling with rumour and secrets, the town is gripped with fear of a serial killer. But the truth could be even darker.

Not everyone who’s lost wants to be found

Surrounded by people and places she tried to forget, Paula digs into the cases as the truth twists further away. What’s the link with two other disappearances from 1985? And why does everything lead back to the town’s dark past – including the reasons her own mother went missing years before?

Nothing is what it seems

As the shocking truth is revealed, Paula learns that sometimes it’s better not to find what you’ve lost.

Claire McGowan was born in 1981 and grew up in a small village in Northern Ireland. After completing a degree in English and French at Oxford University she moved to London and worked in the charity sector. She now lives in Kent and also teaches creative writing.

The Lost

is her second novel.

By Claire McGowan and available from Headline

The Fall

The Lost

For Oliver

I’d like to thank everyone at Headline for their support and belief in the book, especially Ali Hope, Veronique Norton, and Sam Eades.

Thanks to the staff at

Johnson & Alcock and Blake Friedmann literary agencies, especially Oli Munson.

Thanks to everyone who has helped me with bits of research and information, especially Oliver Sindall and Eileen Dorgan for psychological and medical information. At this point writers always say ‘and any remaining mistakes are my fault’. In this case it’s entirely true – they are definitely my fault and in some places I’ve deliberately changed how things might function in Ireland. Thanks also to my contacts in the PSNI who didn’t want to be named for security reasons, and to my mum and dad for spotting general and medical mistakes. I’m also sorry if I forgot anyone (it’s been a while!).

Thanks to everyone who read and commented on early bits of the manuscript, including Mary Flanagan at City Lit and members of the writing class there. Big thanks to Sarah Day, top reader, writer, and friend. Thanks also to everyone at the York Festival of Writing, who were very enthusiastic about the first 3,000 words of this book.

I’m very grateful to anyone who took the time to review my previous book, in print or online, and the bookshops which have supported me – especially Goldsboro Books in London, No Alibis in Belfast, and Waterstones in Newry. I’d like to pay a big tribute to everyone in the crime world who’s helped me, even (especially) if it was just listening to me moan about the book over a drink. Especial thanks to Peter James, Tom Harper, Declan Burke, Michael Ridpath, Will Carver, Stav Sherez, Tom Wood, Erin Kelly, Jake Kerridge, S. J. Bolton, and Elizabeth Haynes (for help with research and being generally very kind).

The town of Ballyterrin

is fictional (the name translates roughly as

Border Town

), though it occupies a similar (but not identical) geographical location to my hometown of Newry. Apart from this, similarity to real people or places is unintended – although I might have stolen a few jokes off my dad. The cases in the book are also fictional, but for a chilling true-life account of Ireland’s missing people, you could do worse than read

Without Trace: Ireland’s Missing

by Barry Cummins.

Finally, thanks to my home crew: Oliver (for general maintenance and always being my first reader), and Eddie the beagle (for chewing through the laptop cable and burying bits of the manuscript in the garden. Not that helpful actually but good company).

If you’ve enjoyed the book, I’d love to hear from you. Visit my website at

http://clairemcgowan.net

, or find me wasting time on Twitter, where I am

@inkstainsclaire

.

York, May

‘Imagine all of

you went missing.’

She waited until they were all listening, putting down their pens on top of blank paper pads, sitting up straight. Light filtered in through the dusty blinds of the room.

‘Every two minutes in this country, someone disappears – that’s over 200,000 a year.’ She paused so they could take in the numbers. They were listening now; attentive. Mostly middle-aged men, a few women dotted here and there. Nobody younger than her.

She clicked the next slide. ‘Research shows we can divide the missing into four main groups. If we take a hypothetical one hundred people – all of you here – statistically, sixty-four will have gone missing voluntarily. Money trouble, family breakdown . . . many reasons.’

I can’t go on. I just can’t bear it any more.

‘Around nineteen in the hundred will drift away. People in this category typically have weak societal bonds, addiction problems – drugs, alcohol.’

Envelopes piling up in a hallway

, Return to Sender

scrawled across the name

. ‘Many in these groups will come home again, or be found safe years later.’

She clicked again, and in the dark they scribbled down her words. ‘And some people don’t mean to go missing. They just get lost somehow, on the way to the shops or the bingo hall. They may not remember who they are, where they’re meant to be.’

Something slipping out of your pocket, a loss you don’t even feel until it’s too late.

‘This group makes up sixteen out of the hundred.’

Some in the audience

had begun to count, and she could see they knew what she’d say next.

‘This leaves the one per cent. Among the missing, this is the one who didn’t want to go. Who knew exactly where they were going, and remembered their own name. The reason this person disappeared is what keeps me awake at night. Who took them? What happened?

Where are they

?’

She could see them nod, taking notes, and she stopped and put down her laser-pointer, and didn’t say the rest, what was really on her mind when she ran these numbers and figures. W

hen I think about her – which I try not to do – I hope she wasn’t in the one per cent. But sometimes, I must admit, I hope she was – because otherwise, it means she

wanted

to go.

Berkshire, September

There was no point

in running.

Everyone knew that. The response team knew, crouching in the early dawn. It was the first morning it had felt really cold, and a wintry sun tinted the windows of the vans where they huddled. The reporters half a mile off in the village, doing hushed live broadcasts, they knew. ‘

As police move in to search for missing Kaylee Morris, hope is fading fast

. . .’ Even the girl’s parents, staring at blank walls back in the police station, squeezing the blood from each other’s hands, they knew too, deep down. After a month gone, taken on her way home from school, the police weren’t likely to find her alive. A body, maybe, for the parents to bury. Better than not knowing. Gentle lies that she hadn’t suffered.

No, there was no point in running up the damp field to the ramshackle cottage on the hill. But when the lead officer silently lifted his Hi-Vis arm, she was out and moving too, over the wet ground. Her feet squelched, red hair tangled in her face. Ragged breaths tore her lungs. She reached the trees and crashed through, branches ripping at her face, and only stopped when strong arms pinned her.

A voice in her ear. ‘Where the

hell

are you going? I told you to stay put!’

She struggled. ‘Please. I have to!’

The policeman’s face was kind

between his helmet and bright jacket. ‘Let it go, Paula. You’ve done your bit.’ Ahead of them, dark figures took up silent positions round the cottage. Paula sagged and gave up. The sky was streaking pink with dawn. Overhead, the trails of planes to Heathrow, oblivious. And up in the house, a single light was burning.

At times like this, Paula liked to focus her eyes on a jokey plaque someone had pinned up behind the boss’s bald head.

You don’t have to be mad to work here, but it helps

. Was it possible he’d put it there? Could there be a spark of humour somewhere inside the red-faced man who was currently reading her the riot act? She tuned in from time to time, just to keep the thread of what it was she’d done.