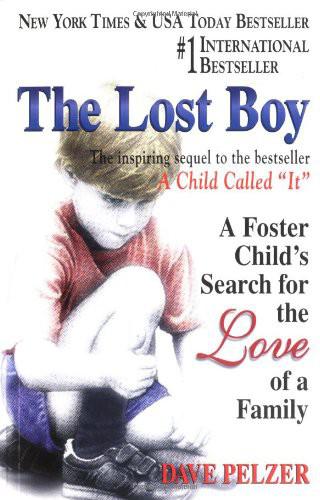

The Lost Boy

Authors: Dave Pelzer

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography, #Autobiography, #Memoir

To the teachers and staff who rescued me

Steven Ziegler

Athena Konstan

Joyce Woodworth

Janice Woods

Betty Howell

Peter Hansen

the school nurse of

Thomas Edison Elementary School

and the Daly City police officer

To the angel of social services

Ms Pamela Gold

To my foster parents

Aunt Mary

Rudy and Lilian Catanze

Michael and Joanne Nulls

Jody and Vera Jones

John and Linda Walsh

To those with a firm but gentle guiding hand

Gordon Hutchenson

Carl Miguel

Estelle O’Ryan

Dennis Tapley

To friends and mentors

David Howard

Paul Brazell

William D. Brazell

Sandy Marsh

Michael A. Marsh

In memory of Pamela Eby

who gave her life to saving the children of Florida

To MY

PARENTS

, who always knew

Harold and Alice Turnbough

And finally, to MY

SON

, Stephen

whose unconditional love for who I am and what I do keeps me going.

I love you with all my heart and soul.

Bless you all, for,

“

It takes a community to save a child.”

This book would not have been possible without the tenacious devotion of Marsha Donohoe – editor extraordinaire – of

Donohoe Publishing Projects.

It was Marsha who not only edited the entire text from the original, dismayed

printed

version, but who also typeset, copyedited and proofread the tome to simplify the publication process. And, more important, she maintained the rigid, chronological perspective of the continuing journey through the eyes of a bewildered child. For Marsha, it was a matter of

“... If I Could.”

Thank you to Christine Belleris, Matthew Diener and Allison Janse of the editorial department for their professionalism throughout the production of this book. And a special thank you to Matthew for handling all of our needs and last-minute requests with a smile, and expertly following through on everything.

To Irene Xanthos and Lori Golden of the sales department of Health Communications, Inc., for their undying genuine sincerity. And to Doreen Hess for all her kindness.

A gargantuan thank you to Laurel Howanitz and Susy Allen of

Hot Guests

, for their unyielding dedication and promotion. Thanks for believing.

To Cindy Edloff, for her efforts and time.

A special thank you to the owners and staff of

Coffee Bazaar

in Guerneville, California, for keeping the raspberry mochas coming, for allowing Marsha and me to plug in and camp out, and for providing us with “The Big Table” -enabling us to spread out, take over and promote chaos within the quiet confines of this serene setting.

Some of the names in this book have been changed in order to protect the dignity and privacy of others.

As in the first part of the trilogy,

A Child Called “It”,

this second part depicts language that was developed from a child’s viewpoint. The tone and vocabulary reflect the age and wisdom of the child at that particular time.

The perspective of

A Child Called “It”

was based on the child’s life from ages 4 to 12; the perspective of

this

book is based on life from ages 12 to 18.

Winter 1970, Daly City, California –

I’m alone. I’m hungry and I’m shivering in the dark. I sit on top of my hands at the bottom of the stairs in the garage. My head is tilted backward. My hands became numb hours ago. My neck and shoulder muscles begin to throb. But that’s nothing new – I’ve learned to turn off the pain.

I’m Mother’s prisoner.

I am nine years old, and I’ve been living like this for years. Every day it’s the same thing. I wake up from sleeping on an old army cot in the garage, perform the morning chores, and

if

I’m lucky, eat leftover breakfast cereal from my brothers. I run to school, steal food, return to “The House” and am forced to throw up in the toilet bowl to prove that I didn’t commit the crime of stealing any food.

I receive beatings or play another one of her “games, ” perform afternoon chores, then sit at the bottom of the stairs until I’m summoned to complete the evening chores. Then, and only

if

I have completed all of my chores on time, and

if

I have not committed any “crimes, ” I

may

be fed a morsel of food.

My day ends only when Mother allows me to sleep on the army cot, where my body curls up in my meek effort to retain any body heat. The only pleasure in my life is when I sleep. That’s the only time I can escape my life. I love to dream.

Weekends are worse. No school means no food and more time at “The House.” All I can do is try to imagine myself away -somewhere, anywhere -from “The House.” For years I have been the outcast of “The Family.” As long as I can remember I have always been in trouble and have “deserved” to be punished. At first I thought I was a bad boy. Then I thought Mother was sick because she only acted differently when my brothers were not around and my father was away at work. But somehow I always knew Mother and I had a private relationship. I also realized that for some reason I have been Mother’s sole target for her unexplained rage and twisted pleasure.

I have no home. I am a member of no one’s family. I know deep inside that I do not now, nor will I ever, deserve any love, attention or even recognition as a human being. I am a child called “It.”

I’m all alone inside.

Upstairs the battle begins. Since it’s after four in the afternoon, I know both of my parents are drunk. The yelling starts. First the name-calling, then the swearing. I count the seconds before the subject turns to me –

it always does. The sound of Mother’s voice makes my insides turn. “What do you mean?” she shrieks at my father, Stephen. “You think I treat

The Boy

‘

bad? Do you?” Her voice then turns ice cold. I can imagine her pointing a finger at my father’s face. “You … listen

... to …

me. You … have no idea what

It’s

‘

like. If you think I treat

It

‘

that bad … then …

It

‘

can live somewhere else.”

I can picture my father – who, after all these years, still tries somewhat to stand up for me – swirling the liquor in his glass, making the ice from his drink rattle. “Now calm down, ” he begins. “All I’m trying to say

is …

well… no child deserves to live like that. My God, Roerva, you treat… dogs better than … than you do The Boy.”

The argument builds to an ear-shattering climax. Mother slams her drink on the kitchen countertop. Father has crossed the line. No one

ever

tells Mother what to do. I know I will have to pay the price for her rage. I realize it’s only a matter of time before she orders me upstairs. I prepare myself. Ever so slowly I slide my hands out from under my butt, but not too far -for I know sometimes she’ll check on me. I know I am never to move a muscle without

her

permission.

I feel so small inside. I only wish I could somehow …

Without warning, Mother opens the door leading to the downstairs garage. “You!” she screams. “Get your ass up here! Now!”

In a flash I bolt up the stairs. I wait a moment for her command before I timidly open the door. Without a sound I approach Mother and await one of her “games.”

It’s the game of address, in which I have to stand exactly three feet in front of her, my hands glued to my side, my head tilted down at a 45-degree angle and my eyes locked onto her feet. Upon the first command I must look above her bust, but below her eyes. Upon the second command I must look into her eyes, but never, never may I speak, breathe or move a single muscle unless Mother gives me permission to do so. Mother and I have been playing this game since I was seven years old, so today it’s just another routine in my lifeless existence.

Suddenly Mother reaches over and seizes my right ear. By accident, I flinch. With her free hand Mother punishes my movement with a solid slap to my face. Her hand becomes a blur, right up until the moment before it strikes my face. I cannot see very well without my glasses. Since it is not a school day, I am not allowed to wear them. The blow from her hand burns my skin. “Who told you to move?” Mother sneers. I keep my eyes open, fixing them on a spot on the carpet. Mother checks for my reaction before again yanking my ear as she leads me to the front door.

“

Turn around!” she yells. “Look at me!” But I cheat. From the corner of my eye I steal a glance at Father. He gulps down another swallow from his drink. His once rigid shoulders are now slumped over. His job as a fireman in San Francisco, his years of drinking and the strained relationship with Mother have taken their toll on him. Once my superhero and known for his courageous efforts in rescuing children from burning buildings, Father is now a beaten man. He takes another swallow before Mother begins, “Your father here thinks I treat you bad. Well, do I? Do I?”

My lips tremble. For a second I’m unsure whether I am supposed to answer. Mother must know this and probably enjoys “the game” all the more. Either way, I’m doomed. I feel like an insect about to be squashed. My dry mouth opens. I can feel a film of paste separate from my lips. I begin to stutter.

Before I can form a word, Mother again yanks on my right ear. My ear feels as if it were on fire. “Shut that mouth of yours! No one told you to talk! Did they? Well, did they?” Mother bellows.

My eyes seek out Father. Seconds later he must have felt my need. “Roerva, ” he says, “that’s no way to treat

The Boy.”

Again I tense my body and again Mother yanks on my ear, but this time she maintains the pressure, forcing me to stand on my toes. Mother’s face turns dark red. “So you think I treat him badly? I…” Pointing her index finger at her chest, Mother continues. “I don’t need this, Stephen, if you think I’m treating

It

badly … well,

It

can just get out of my house!”

I strain my legs, trying to stand a little taller, and begin to tighten my upper body so that when Mother strikes I can be ready. Suddenly she lets go of my ear and opens the front door. “Get out!” she screeches. “Get out of my house! I don’t like you! I don’t want you! I never loved you! Get the hell out of my house!”

I freeze. I’m not sure of this game. My brain begins to spin with all the options of what Mother’s real intentions may be. To survive, I have to think ahead. Father steps in front of me. “No!” he cries out. “That’s enough. Stop it, Roerva. Stop the whole thing. Just let The

Boy

be.”

Mother now steps between Father and me. “No?” Mother begins in a sarcastic voice. “How many times have you told me that about The

Boy? The Boy

this.

The Boy

that.

The Boy, The Boy, The Boy.

How many times, Stephen?” She reaches out, touching Father’s arm as if pleading with him; as if their lives would be so much better if I no longer lived with them – if I no longer existed.

Inside my head my brain screams,

Oh my God! Now I know!

Without thinking, Father cuts her off. “No, ” he states in a low voice. “This, ” he says, spreading his hands, “this is wrong.” I can tell by his trailing voice that Father has lost his steam. He appears to be on the verge of tears. He looks at me and shakes his head before looking at Mother. “Where will he live? Who’s going to take care

of…

?”

“Stephen, don’t you get it? Don’t you understand? I don’t give a damn what happens to him. I don’t give a damn about

The Boy.”

Suddenly, the front door flies open. Mother smiles as she holds the doorknob. “Okay. All right. I’ll leave it up to

The Boy.”

She bends down, just inches in front of my face. Mother’s breath reeks of booze. Her eyes are ice cold and full of pure hatred. I wish I could turn away. I wish I were back in the garage. In a slow, raspy voice, Mother says, “If you think I treat you so badly, you can leave.”

I snap out of my protective mold and take a chance by looking at Father. He misses my glance as he sips another drink. My mind begins to tumble. I don’t understand the purpose of her new game. Suddenly I realize that this is no game. It takes a few seconds for me to understand that this is my chance – my chance to escape. I’ve wanted to run away for years, but some invisible fear kept me from doing it. But I tell myself that this is too easy. I so badly want to move my legs, but they remain rigid.

“

Well?” Mother screams into my ear. “It’s your choice.” Time seems to stand still. As I stare down at the carpet, I can hear Mother begin to hiss. “He won’t leave.

The Boy

will never leave.

It

hasn’t the guts to go.”