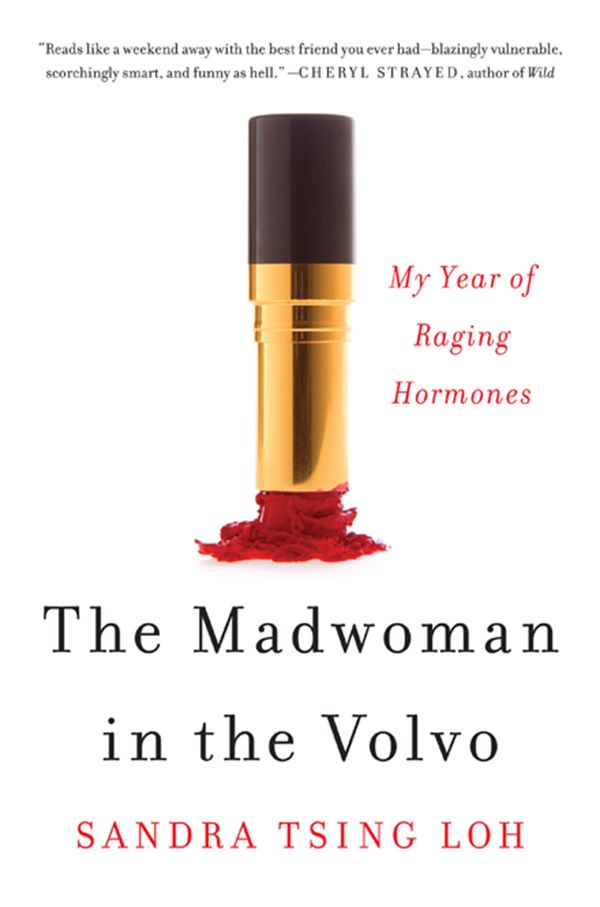

The Madwoman in the Volvo: My Year of Raging Hormones

Read The Madwoman in the Volvo: My Year of Raging Hormones Online

Authors: Sandra Tsing Loh

The

Madwoman

in the

Volvo

MY YEAR OF RAGING HORMONES

Sandra Tsing Loh

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York · London

For my mother,

Gisela, and all the world’s other

fabulous Madwomen

CONTENTS

Life in the (Happiness) Projects

A Brief Discussion of Manopause

Parenting Adolescents During Perimenopause, or Medieval Times

Bench Warrant for My Father’s Arrest

The

Madwoman

in the

Volvo

I

’

M HURTLING WEST ALONG

the 101 Freeway to the Valley to pick my daughters up from school. I am forty-nine years old, and I have just gotten off the phone with my friend and magazine editor, Ben. We have been talking about refinancing: It’s a wonderfully mundane topic of conversation—one of those truly harmless pleasures of midlife. It helps me to recall not all, but at least some, of the staid, rational person I was not too long ago: which is to say before I, a forty-something suburban mother, became involved in a wild and ill-considered extramarital affair.

“Listen,” Ben says excitedly. “I know two years ago John Warick got you that thirty years fixed at 4.75 percent, which as we know is historically unheard of. But I’m telling you, this new guy who’s doing my next refinance, at Wells Fargo? When I ran your numbers by him, he thought you could qualify for an even lower thirty years fixed like . . . 4.275.” Ben is as much of a math nerd about this stuff as I am.

Indeed, under normal circumstances, I am the sort of OCD person for whom the number 4.275 would create a spike of excitement. It’s the same adrenaline rush I get when successfully completing a newspaper sudoku or crossword puzzle with a sharp number 2 pencil. Ben and I can get truly wound up around our small personal-finance triumphs most of the time. But today even this conversation hasn’t supplied its usual lift. I find myself feeling surprisingly flat.

Until now, not being able to feel things has never been one of my copious personal flaws. I am, for better or for worse, a person obsessively driven by passions large and small. I find my mind drifting to dinner. I remember in that moment that I promised my girls that morning that tonight’s dinner would be Make Your Own Pizza.

IN THEORY

Make Your Own Pizza is one of the wonderfully creative new things my girls and I do. Now that my kids go back and forth between my ex-husband and me, I have periods of rest. As a consequence, I’ve been able to bring on an astonishing amount of high-quality parenting. Ironically, here is the artisanal attention and care I was never able to provide as a full-time mother. In our new life together in our big short-saled Victorian house, my girls and I make lemonade from scratch, bake pies, and paint Easter eggs. I’ve taught them to ride bikes, to crochet, and to paint on actual easels with watercolors. We even go bowling, and we have Make Your Own Pizza for dinner.

I find myself thinking ahead to the burned pizza stone languishing crusty and unwashed in the oven. I think of how sticky the Trader Joe’s dough is, of how I will probably need to get two kinds, the garlic-herb and the whole wheat. I think of how needlessly jam-packed the parking lot at Trader Joe’s is in midafternoon, how surprisingly uninspired their samples—lukewarm cups of bland organic rotelli, cloudy vials of unfiltered apple juice. My feeling of flatness gives way decidedly, at the thought of Make Your Own Pizza, to sudden and dramatic gloom.

I hang up on Ben, pull off the freeway, and park under a tree in front of a dirty-yellow ranch-style house to collect myself and instead instantly begin sobbing, producing heaves of seawater like Jonah’s whale. It’s not just the pizza. Suddenly an image comes to me, seemingly at random, of my daughters’ hamster. Because they are always begging for more pets, their dad had given them a toffee-blond hamster named Hammy, who stayed with me one weekend when they all went out of town. He spent the day as my little companion, happily rolling around in his blue plastic ball while I wrote at the computer. After Hammy went home I heard from the girls that he had gotten sick—“Probably from eating his own wood chips,” Sally reported—and subsequently died.

Hunched over the steering wheel, I think—why now?—of that little face, those little paws, that jingling blue ball. I think of Hammy’s sunny disposition and friendly, inquisitive nose, and his essential innocence and trueness and goodness. I am a forty-nine-year-old woman sitting in her filthy Volvo parked under a tree on a Tuesday afternoon wailing about a hamster. Just how low are we setting the bar here? (And yet, why of all things did God have to take this hamster? What was the harm?)

I want to call my older sister, Kaitlin, but I shouldn’t. My sister and I are so close it’s as if we share a limb. When Kaitlin and I are getting along, we talk all the time, and she gives the greatest, most amazing sister advice (call that Pema Chödrön, after the crop-haired Tibetan-Buddhist nun whose inspirational writings we both adore). When we are fighting I can almost physically feel the phone not ring, and it feels intentionally strategic (call that . . . Margaret Thatcher). But I’ve put Kaitlin through a hell of a lot. My affair almost killed her. After all, I’m not just her middle-aged kid sister but the mother of her two favorite nieces. No, I can’t call her, because if she sensed I was going off the deep end again, Kaitlin would have to stage an intervention to treat the entire family.

Instead I find myself dialing Ann. Ann is not necessarily my closest girlfriend, but she is the most sensible and the longest happily married. (I’ve had my share of crazy girlfriends, and since my divorce it seems like everyone else’s twenty-year-long marriages are now suddenly toppling over like dominoes. All these wild-eyed women want to meet for coffee, as though I’m a sort of underground-divorce-railroad Harriet Tubman, and the vibe is unsettling.) Ann is together. Ann always has a good plumber, contractor, or electrician. Ann knows which Beverly Hills specialist to call if you have a mysterious spot or rash. Ann has a beautifully organized shoe closet.

“Hello?” Ann says after two and a half rings. Barely able to choke the words out, I tell her about my sorrow over the hamster, and about this sudden, violent stab of midafternoon midlife malaise.

She says: “Oh sweetie. I’m so sorry to hear that. Can I ask—when did you last have your period?”

“I have no idea. I can barely keep food in the fridge and my daughters in underwear.”

“But might you have missed any?”

“Oh sure.” I frown. Good God—who keeps track of periods anymore?

“I think . . . ? Maybe . . . ? Because it sounds so familiar . . . ? You may not want to hear this, but you could be entering menopause.”

“Menopause?!” I cry out in relief. “Just menopause? That would be awesome! I thought I was going mad or something!”

But now Ann goes on to describe a personal daily routine that is about the most complicated one I have ever heard of. It is a rigorously titrated cocktail of antidepressants, bioidenticals, walks, facials, massages, dark chocolate, and practically throwing salt over the left shoulder.

“And it’s most intense at that certain time of the month. That’s when I have these bouts of progesterone depression balanced with rage—tons and tons of rage. I’m shouting on the streets, in traffic, at my husband. I almost killed someone in the parking lot at B of A. I can feel like I’m really going crazy. I throw things. For no reason. Weird things set me off. So just for those days—it’s four to five days—I have to up my Estrovel. If I remember. The hardest thing is just to remember.” She recommends her dream gynecologist, Dr. Valerie. I take the number without admitting that I’m not sure I’m ready to see a doctor, because quite frankly I can’t face being weighed.

Later I’ll go home to my laptop for a crash course in the history of the change. Wow—there’s so much I didn’t know. Menopause was first mentioned in ancient Greece by writers like Aristotle, who pegged both menstrual periods and fertility as ending at the same time for women, then around age forty. Cited in European scholarly texts in the Middle Ages, menopause took an unattractive turn in 1816 when the French physician Charles de Gardanne termed “ménopause” a nervous disorder. This no doubt contributed to medical thinking in the later 1800s that menopause was a time when a woman “ceased to exist for the species” and “resembled a dethroned queen” (these from a description of female diseases). The first complete book on menopause, with the warm and fuzzy title of

The Change of Life in Health and Disease

(1857), by John Edward Tilt, apparently cites 135 different menopause symptoms, including curious manifestations like pseudonarcotism, temporary deafness, uncontrollable peevishness, and “hysterical flatulence.” Yikes!

By contrast, it appears that non-European cultures have more organic, female-friendly approaches to menopause. Mayan women famously report not having any negative menopausal symptoms at all. American Indian women and their faraway Chinese sisters have long treated menopausal symptoms with such healing natural remedies as angelica (dong quai). In India a woman’s ascent into this next, nonmothering phase of life is seen as a sacred time of greater spiritual depth and exploration. Instead of “ceasing to exist for the species,” for Hindu women menopause opens the door to enlightenment, growth, and wisdom. As I’ll learn in the chapters to come, enlightenment, growth, and wisdom are only part of the package.