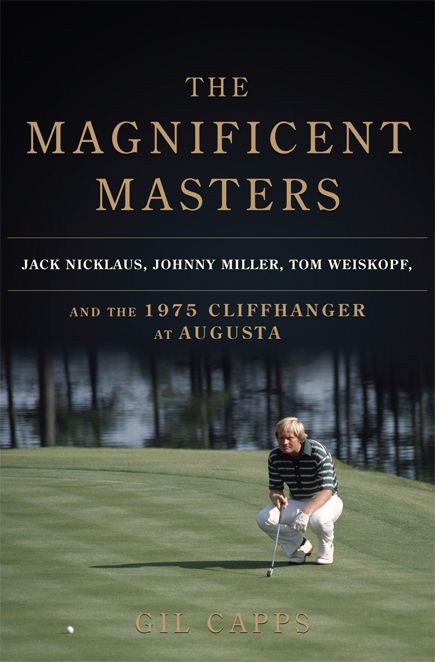

The Magnificent Masters: Jack Nicklaus, Johnny Miller, Tom Weiskopf, and the 1975 Cliffhanger at Augusta

Authors: Gil Capps

THE

MAGNIFICENT

MASTERS

Copyright © 2014 by Gil Capps

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Set in 11.5 point Adobe Caslon Pro by Marcovaldo Productions, Inc. for the Perseus Books Group

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the

Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2014

ISBN: 978-0-306-82185-1 (eBook)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA, 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

special.markets@perseusbooks.com

.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Julie, Katie, and Ellie

And Mom and Dad

CONTENTS

1

|

The Masters

A Note on Sources and Bibliography

T

he greatest golfer of all time squatted down to study his line. Thousands upon thousands of different putts existed on any of the course’s eighteen greens, with various hole locations, infinite angles, and boundless distances. None were more difficult to judge than this one—forty feet, uphill, along a pronounced ridge with a break to the left that was nearly impossible to read.

Arriving on the teeing ground just 170 yards behind him, his two keenest rivals watched intently. They had been chasing him, not only through the dramatic twists and turns of this final round, but their entire lives, each dreaming of the day they would eclipse this man on the game’s most exalted stage. The next thirty seconds would alter the careers of all three men, and therefore, the game of golf.

What brought them to this juncture? A simple invitation.

3160 CARISBROOK ROAD, COLUMBUS 21, OHIO

The area most sensitive to touch are the fingers. Doctors believe that some people have extraordinary senses, allowing them to process information through feel that others can’t. Elite golfers are such a group. This nineteen-year-old boy from the suburban Upper Arlington

neighborhood of Columbus knew nothing about that. He did know that he’d never felt an envelope like the one that arrived at his parents’ house in February 1959 addressed to him. It was larger than a normal letter envelope—six-and-a-half inches by four-and-three-fourths inches—and ivory-colored with a first-class four-cent stamp pasted in the top-right corner. Its weight stood out, conveying an importance of its contents. The pair of hands, smaller than average for a boy of his six-foot height and stocky build, opened the envelope with great care, only to find another inside. Handwritten on this one was a name: “Mr. Nicklaus.”

What the young man saw upon opening the inner envelope could not have made Emily Post prouder. It was perfect. All of the elements of a formal invitation had been carried out with precision. It was printed on the finest of quality paper stock with a raised border just inside the edges. The words were engraved and centered below the invitee’s insignia. The invitation was phrased in the third person. Punctuation was placed for separation of words only on the same line—for heaven’s sake, never at the end of a line. The state, month, days, and year were all spelled out—no abbreviations. The who, what, where, when, and how to respond were clear as he read the dark green lettering: “The Board of Governors of the Augusta National Golf Club cordially invites you to participate in the Nineteen Hundred and Fifty-Nine Masters Tournament to be held at Augusta, Georgia the second, third, fourth, and fifth of April.” At the bottom was the name of his hero: “Robert Tyre Jones, Jr., President.”

Jack William Nicklaus had been asked to play in what was becoming the world’s most prestigious golf tournament—the Masters. For any young aspiring golfer, this was their debutante ball.

No one was more excited than his father Charlie. He knew the proper etiquette. R.S.V.P. was tagged on the bottom left of the invitation. A prompt, handwritten reply needed to be sent to the return address on the back of the envelope. The elder Nicklaus quickly began drafting a response—mindful to find just the right phrases to

match the significance of the invitation. Once satisfied, he would have his son copy what he had composed and send the letter of acceptance back to Augusta National Golf Club.

At the Nicklaus house, the invitation had not been unexpected, but as any good host knows, all of its guests must be invited the same way. On January 31, Nicklaus had been one of nine Americans named by the United States Golf Association for the upcoming Walker Cup—a biennial match-play competition between amateurs from the United States and amateurs from Great Britain and Ireland. Being a Walker Cupper at the time meant a trip to the Masters—one of thirteen categories in which players could earn an invitation to the tournament. His short-term goal had been the Walker Cup; however, his long-term one was to be the best golfer ever to play the sport.

The Masters and the Walker Cup presented a unique opportunity, but Nicklaus was a freshman at Ohio State University. His trip to Great Britain in May would be a four-week endeavor. The team was staying afterward to compete in the British Amateur Championship as well. Nicklaus consulted with his college golf coach Bob Kepler, and they both agreed Nicklaus should take off the spring semester.

With no classes standing in his way, Nicklaus decided to head to Augusta early. He filled up the car with gas—the average price per gallon being thirty-one cents that year. The interstate highway system had been authorized only three years earlier, so the 600-mile journey south wouldn’t be speedy. His childhood friend Robin Obetz—“Bob” to Nicklaus—tagged along. Obetz, on spring break, was one of Nicklaus’s best friends growing up and would serve as the best man in his wedding the following summer.

They arrived in Augusta on Friday, March 20—a full thirteen days before the first round—and the naïve collegians quickly learned about club protocol. “I didn’t know I couldn’t take anyone with me,” says Nicklaus. “Nobody even said a word about it.” Luckily for the boys, Alec Osborne, a club member and advertising executive,

recognized the situation and quietly stepped in to take Obetz on as his guest.

Nicklaus was the youngest player in the field in 1959—a distinction that drew media attention. “I’ve been looking forward to qualifying for this tournament for three years now,” Nicklaus told

Augusta Chronicle-Herald

sports columnist Johnny Hendrix. The day after arriving, Nicklaus played his very first round ever at Augusta National. He bogeyed the 2nd, 4th, and 14th holes before recording his first birdie on the par-five 15th, where he hit the green in two shots and two putted for birdie. He made another birdie on the following hole, knocking in a five-foot putt on the par-three 16th. Nicklaus shot a one-over-par 73.

“I liked it. I enjoyed it,” says Nicklaus of his first experience there. “I felt the golf course was very much suited to how I played.”

Nicklaus practiced and played and played and practiced for three days. He had planned to stay longer, but he hadn’t played competitively all year. So he made a call to officials at the Azalea Open in Wilmington, North Carolina, that week’s stop on the professional tour. “They said, ‘Sure you’re a Walker Cup player, you can get right in the tournament’,” says Nicklaus. But what they meant was he could play in the qualifier for the tournament, which a displeased Nicklaus found out about when he arrived. He qualified anyway, and being nineteen, says, “I was kind of ticked off because they backed out of what they said they’d do.” Nicklaus shot 74–74 the first two rounds and sat in 18th place, ten shots behind Art Wall. “I said, ‘I’ve had enough tournament golf, to heck with this’,” recalls Nicklaus. So he withdrew and headed back to Augusta for more practice. That didn’t please Ed Carter and Joe Black—the two leading PGA officials at the time. They would catch up to Nicklaus at Augusta and remind him of his responsibilities to sponsors, fans, and himself. “What I did was wrong,” says Nicklaus, who, had he stayed, could have finished 4th in the tournament just by shooting 70–70 in the final two rounds.