The Malice of Fortune (16 page)

Read The Malice of Fortune Online

Authors: Michael Ennis

Tags: #Thrillers, #General, #Historical, #Fiction

I suppose here I should tell you a few things about your

zia

Camilla, who could shame the Seraphs with her goodness. She came to me in

anno Domini

1494, the year the French came to Rome. Charles VIII had arrived with his enormous army in the last days of December, driving Pope Alexander out of the Vatican and into the Castel Sant’Angelo. But His Holiness, though weak in arms and soldiers, was far too clever for the drooling, watery-eyed little king. With the aid of my dear old patron, Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, a truce was negotiated that proved more profitable to the pope than to His Most Christian Majesty.

The French soldiers were allowed into Rome like panthers on leashes. Most of them were held in check, but enough got loose to sack scores of houses, making bonfires of the tables and chairs while they drank our finest wines and sampled without recompense delicacies of various sorts—though King Charles himself had issued a decree that no

cortigiane

were to be harmed. Even the houses of the pope’s chamberlain and the mother of His Holiness’s children—your grandmother—were not spared. And unfortunate servants and Jews often fared little better than the furniture.

I was twenty-six years old in that year, and there was not a man in Rome, from the fuller treading piss in his vats in the Trastevere to the pope on the throne of Saint Peter, who did not know my name; the wages of my notoriety had earned me the best house on the Via dei Banchi. Even now I can still smell those rooms, the orange water and lavender; the flowers I had every day in spring and summer: roses, carnations, jasmine, and hyacinth.

But there was little such

bellezza

on the day I met your

zia

Camilla. I was out in the cold rain, seeing after the

bravi

who always guarded my house—in those difficult days they also informed me as to the whereabouts of the French looters, in the event we should have to flee. I watched the evacuation of the neighborhoods just above the Ponte

Sant’Angelo, where hazy plumes of smoke rose into the leaden sky. These refugees had loaded their mules with whatever they hoped to save: money chests, dresses, silver plate, what have you. I took in several of these distraught souls, who had credulously believed the French pledges, and was about to shut my door when I observed a couple mounted on a mule, trotting right down the Via dei Banchi, but in the direction of all the trouble. He had two good lumps on his nose and white scars on his stubbled cheeks. She was half his age, not more than fourteen, with a child’s slender face and charcoal eyes that had already seen everything.

Surmising that both the mule and the girl had been stolen, I waved the thief to a stop. “Messer,” I said, “where are you going with my friend’s mule?”

He threw back his cape and reached for the sword at his belt—until he saw my

bravi

step out from my doorway. “Who did you say your friend is?” he asked, his eyes slits.

“Donna Vanozza Catanei,” I said, this being your aforementioned grandmother, although her ownership of the mule was entirely my invention. I wanted this thief to think he had just met a better thief.

He gave me a scoundrel’s toothy smile. “That is so. Madonna Vanozza gave me this mule with orders to sell it to the

oltramontani

before they could steal it.” He nodded toward the smoke plumes.

I knew what he intended to sell to the French. “Who is the girl?”

“My sister. When I heard what the monks were doing to her at Santa Cecilia, I took my own flesh out of there, may a better God now protect her.”

“Truly? And here I am looking for someone to recite the Litany of Saints.” I could see from the girl’s bare, purple feet that she had come from the dye vats instead of the convent, but you couldn’t say which was worse. “For which do you think the French are likely to pay more, your little sister-sister or the mule?”

He pumped his heels at the mule’s ribs but I nodded to my boys to grab the halter. I told the rascal, “I think it will matter less to the

oltramontani

that the mule has already been ridden.” Then I looked carefully at the girl. “Do you want to go with him?”

I knew what her eyes said. After a moment she shook her head.

“Messer,” I said, holding out my arms to the girl, “I leave you the mule.”

So that was how my Camilla came into my house.

She did not trust me for two weeks, although she ate my soup and roasts and took in everything with those agile, all-consuming eyes. Of course she believed that I would use her as I had been used when I was her age—like the girl of Andros. But one day she followed me into my bedroom and stood looking about at all my Greek vases and Roman medallions—with those eyes I didn’t know if she intended to snatch something and run off. Instead this tiny voice emerged: “Madonna, can I live here until Easter?”

I took Camilla in my arms for the first time since I had lifted her from that mule. And I gave her at least a dozen kisses before I said, “You can live here forever.”

That was when she began to tell me her story. Like me, she was born in the dirt, in her instance the red dust of the Neapolitan Campania. The rest was a tangled tale, much of which even she couldn’t unravel, but it is sufficient to say that she was sold like a basket of fat Spanish olives to another family, to serve as a companion to their daughter, only to be put on the street when the little girl died of plague. After that she suffered in as many guises as Ovid’s Mestra, until at last she found herself treading cloth in a dye vat near Monte Mario, from which she was soon enough chased by the French soldiers pillaging there. Having no place to go, she had been offered the poisonous charity of the lout from whom I had retrieved her.

I taught my darling Camilla to read, as my mother had taught me, and that was the beginning of our love. In the end she did not profit, because she spent more years with me in the Trastevere than in our palazzo on the Via dei Banchi. But without Camilla I would not have survived the day you came into this world, and when she might have made her own life, she stayed with you, my precious son, as if you were her own. She was my first baby, you were my second. I was your first mother, and she was your second.

I will say no more, except that our angel’s love is woven into the weft of your soul as well as mine, and nothing can ever draw it out.

X

When we reached the corner where Messer Niccolò had earlier kept watch on Leonardo’s palazzo, I said, “There is an alley alongside,” having studied the great house well enough myself. “Let us see what they have in back.” The towering façade offered only barred windows and the massive oaken door.

The unpaved alley led us to an ill-kept garden where flowerpots lay tumbled amid a small, overgrown orchard. Behind a low brick wall was cleared ground, mostly planted with squash, lying beneath a pale carpet of snow that extended to the city wall. For a moment I looked about in melancholy wonder, remembering our own little garden in the Trastevere. I saw you and dear little Ermes running about, Camilla chasing behind you both. Now all I wanted in this world was to hear your laugh again.

Messer Niccolò and I examined the back of the house. The smaller windows on the ground floor were covered with iron grates; the arched windows on the piano nobile were merely shuttered, though a good ten

braccia

above us. After thrashing about in the snow-sprinkled shrubs, we located a crude ladder, merely a long pole with scraps of lumber nailed to it every

braccia

or so.

When we had wrestled the ladder against the stone lip of one of the windows, I told Niccolò, “I will go in.”

He looked at me as if I were mad.

“Can you say that you have earned a living stealing from men’s houses?”

His smile was quick but sad. “As an honest servant of the Florentine republic, I earn no living at all. I am in debt for my expenses here and still waiting for my appropriation.”

I began to climb, the scrap steps creaking, my gloves shredded by splinters. Upon reaching the shutters I forced them open with my knife and sat on the broad windowsill, letting my legs hang into the house. I was able to make out quite a large room; probably it had once been a bishop’s

sala grande

. Indeed it appeared to have been set up for a banquet, the three large trestle tables already having a great many objects on them, though I could not say what they were.

It was not a long drop to the floor beneath me, but before I could leap my breath caught in my throat.

The blank, ghostly face hovered almost directly opposite me. I thought,

I have found her head

.

But this was something only a bit less ghastly. Evidently a whited human skull had been placed upon the broad cornice that ran around the walls, in the fashion that small antiquities are often displayed. Wondering if this room contained other items Maestro Leonardo had obtained from corpses, I decided to search it first.

I observed the faint glow of a brazier near the open doorway and padded over to light the candle stuck in my belt. When I turned around again I discovered, tumbled and strewn upon those banquet tables, a new world.

With each step, my flickering light illuminated one marvel and then the next: A bleached thighbone might sit next to a Herodotus bound in leather, atop of which rested something like a miniature millworks, with sequences of tiny wooden cogs and wheels. Drawings were scattered about like leaves in November, many portraying the human body from without, but others were similar to those Valentino had just shown me, whole lattices of bones, tendons, nerves, and veins, as though they had been stripped intact from the surrounding flesh, like the skeleton of a filleted fish. The light glimmered on mirrors, lenses, calipers, and scales. On myriad scraps of paper measurements had been noted, quantities added, geometry proofs recorded. Yet what most teased my eye were those forms repeated from one thing to the next: a petrified spiral seashell metamorphosed into the cog of some

strange wooden machine, only to be found next in fantastic drawings of spinning whirlwinds and whirlpools.

I wandered for some time, so rapt I almost walked straight past the most important drawing in that room—at least with regard to my quest. Carelessly surrounded by several notebooks and wooden polygons, this diagram had been inscribed in red chalk upon a piece of thin, translucent paper, such as artists employ for tracing copies.

“God’s Cross,” I said aloud. “This is what you were measuring.”

XI

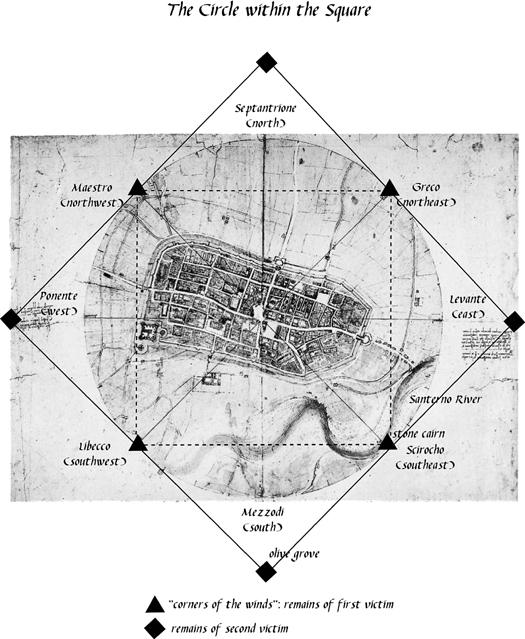

This tracing tissue was somewhat larger than the map Valentino had shown me only an hour or so before. Maestro Leonardo had drawn a circle divided into an octave identical to a wind rose; indeed it appeared that Leonardo had traced this figure from his own map of Imola. He had also made red dots at each of four equally spaced points on the rim of the wheel, so to speak, these no doubt corresponding to the corners of the wind, as Valentino had shown me. And Leonardo had drawn lines between these points, creating a square perfectly fitted within the circle, touching it at only the four corners.

This much I could have expected. But Leonardo had further drawn a larger square around the circle, which touched it at only four points, these tangents being the four corners of the winds; the larger square was in this fashion rotated at an angle to the smaller square, thus giving a sequence of square, circle, square, all fitted perfectly together.

“The circle within the square,” I said aloud, though at that moment I did not entirely understand it.

All at once, it appeared that my candle had waxed considerably brighter. I spun about.

Maestro Leonardo da Vinci stood in the doorway, attired in a farmer’s shirt and an apron, the latter covered with irregular dark spots, which I thought to be paint. With his right hand he held a candle lamp; the tarantula-leg fingers of his left hand appeared to claw at the apron where it covered his breast. Only when I recalled that Leonardo

was said to dissect corpses in his basement did I understand that the apron was a butcher’s smock, the dark spots blood, which he was attempting to wipe from his fingers.

“What do you think you see?”

His sharp tenor now had an authority absent in the olive grove; he seemed to draw strength amid the dazzling disorder of his own intellect. He came to me with the padding gait of a great lion.

Yet for some reason, I was not frightened. When he had come to my side, I said, “The duke has shown me your map. And the corners of the winds.”

“You make a false assumption.” His pitch was higher now, querulous. “These corners of the winds are not my construction.”

“No. But the murderer has imposed them on your wind rose.” I placed my finger on the tracing tissue, directly upon one of the corners of the larger square. “Let us presume that this point represents the location we visited today, in the olive grove. Where we found one quarter of the second woman’s body.” In quick sequence, I moved my finger to each remaining corner of this larger square. “The corners of this square are the locations where you have since found the remaining three quarters of her.” I reasoned that Leonardo and his assistants had gone back out that night, or perhaps Valentino’s people had visited the other three locations during the day. “Once you had measured to that olive grove, you understood how to draw the circle within the square, because the circle was your own wind rose, and you had the first point of the square.”