The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Unsolved Mysteries (77 page)

Read The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Unsolved Mysteries Online

Authors: Colin Wilson

Another eminent experimenter of the 1920s was Dr Eugene Osty, director of the Metapsychical Institute at which the novelist Pascal Fortunny correctly identified the letter from the mass murderer Landru. In his classic work

Supernormal Faculties in Man

, Osty described many experiments in psychometry with various “sensitives”. In 1921 he was handed a photograph of a sealed glass capsule containing some

liquid; it had been found near the great temple at Baalbek. One of his best psychics, a Mme Moral, held the photograph in her hand – it was so blurred it could have been of anything – and said immediately that it reminded her of “a place with dead people”, and of one old man in particular. She “saw” a vast place, like an enormous church, then went on to describe the man, who was obviously a high priest. The capsule in the photograph contained the blood of a man who had been sacrificed in some distant land, and had been placed in the priest’s grave as a memento.

At the time Osty himself had no idea what the photograph represented, and was surprised when the engineer who had found it was able to confirm that it had been discovered in a rich tomb in the Bekaa valley.

This story raises again the central problem about psychometry. Buchanan’s original hypothesis – that it was simply a matter of “nerve aura”, so the psychometrist could be regarded as a kind of human bloodhound – ceases to be plausible if the information can be picked up from a photograph, which could not be expected to retain any kind of “scent”. Even Denton’s assumption that every object somehow “photographs” its surroundings seems dubious. In that case a piece of Roman pavement could only have “photographed” a limited area, and Mrs Denton’s view of Roman legionaries would have been simply of hairy legs towering up above her.

The likeliest hypothesis is that the faculty involved is what is traditionally known as “clairvoyance”, a peculiar ability to “know” what is going on in some other place or at some other time. But Bishop Polk’s ability to distinguish brass in the dark is obviously not clairvoyance. Here, as in so many other areas of the “paranormal”, it is practically impossible to draw neat dividing lines.

Many modern psychometrists – like Gerard Croiset, Peter Hurkos and Suzanne Padfield – have been able use their faculty to help the police solve crimes: Suzanne Padfield was even able to help the Moscow police catch a child-murderer without leaving her home in Dorset. But it is significant that Croiset disliked being called a psychometrist or clairvoyant, and preferred the more ambiguous word “paragnost” – meaning simply the ability to “know” what lies beyond the normal limits of the senses.

44

Rennes-le-Château

The Treasure of Béranger Saunière

The mystery of Rennes-le-Château is the riddle of a poor priest who discovered a secret that made him a millionaire and which profoundly shocked the priest to whom he confided it on his deathbed.

In June 1885 a new curé came to the little village of Rennes-le-Château, on the French side of the Pyrenees; he was 33-year-old Béranger Saunière, and he was returning to the area in which he had been brought up. His early account books survive, and they show that he was very poor – the income on which he supported himself and his housekeeper was the equivalent of six pounds sterling a year.

It was six years later that Saunière decided to restore the church altar, a stone slab cemented into the wall and supported at the other end by two square Visigothic pillars. One of these proved to be hollow, and inside it Saunière found four parchments in wooden tubes. Two were genealogies of local families; the other two were texts from the New Testament, but written without the usual spaces between the letters. It seemed fairly obvious that these were in some sort of code – in fact, the code of the shorter text was straightforward. Saunière only had to write down the letters that were raised above the others, and he had a message that read: “A Dagobert II roi et à Sion est ce trésor et il est la mort”: to Dagobert II, king, and to Sion belongs this treasure, and he is there dead. (The final phrase “et il est la mort” could also be translated “and it is death” – meaning, perhaps, “it is death to interfere with it”.) So these secret messages were about a treasure. Dagobert was a seventh-century French king of the Merovingian dynasty. The author of these parchments was almost certainly a predecessor of Saunière, a priest named Antoine Bigou, who had been the cure of Rennes-le-Château at the time of the French Revolution.

Saunière took the parchments to the Bishop of Carcassonne, Monseigneur Félix-Arsène Billard, and the bishop was sufficiently intrigued

to send Saunière to Paris to consult with various scholars and experts in cryptography. Among these were the Abbé Bieil, director of St Sulpice. Bieil’s nephew was a brilliant young man named Emile Hoffet, who was a student of linguistics. Although Hoffet was training for the priesthood, he was in touch with many “occultists” who flourished in Paris in the 1890s, an era which had seen a revival of interest in ritual magic; Hoffet introduced Saunière to a circle of distinguished artists, which included the poet Mallarmé, the dramatist Maeterlinck and the composer Claude Debussy. It was probably Debussy who introduced Saunière to the famous soprano Emma Calvé, and the relationship that developed between them may have been more than friendship – Saunière was a man who loved women and food.

Before he left Paris, Saunière visited the Louvre and purchased reproductions of three paintings, including Nicolas Poussin’s

Les Bergers d’Arcadie –

the Shepherds of Arcady – which shows three shepherds standing by a tomb on which are carved the words “Et in Arcadia Ego” – usually translated as “I [Death] am also in Arcadia”.

When Saunière returned to Rennes-le-Château three weeks later he was hot on the trail of the “treasure”. He brought in three young men to raise the stone slab set in the floor in front of the altar, and discovered that its underside was carved with a picture of mounted knights; it dated from about the time of King Dagobert. When his helpers dug farther down they discovered two skeletons, and – according to one of them who survived into the 1960s – a pot of “worthless medallions”. Saunière then sent them away, locked the church doors, and spent the evening there alone.

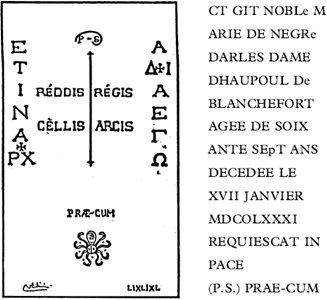

Now Saunière, accompanied by his housekeeper – a young peasant girl named Marie Denarnaud – began to spend his days wandering around the district with a sack on his back, returning each evening with stones which he used to construct a grotto in his garden. Whether this was the only purpose of his explorations is not known. He also committed a rather curious piece of vandalism on a grave in the churchyard. It belonged to Marie, Marquise de Blanchefort, whose headstone had been designed by the same Abbé Bigou who had concealed the parchments in the column. Saunière obliterated the inscriptions on the stone that covered the grave, and removed the headstone completely. However, he was unaware that both inscriptions had already been recorded in a little book by a local antiquary. The inscription on the gravestone is shown opposite:

The vertical inscriptions on either side of the gravestone are easy to read: a mixture of Greek and Latin letters carries the inscription

Et in

Arcadio Ego

– linking it with the Poussin painting. The central inscription: “Reddis Regis Cellis Arcis” may be read: “At royal Reddis, in the cave of the fortress”. “Reddis” is one of the ancient names for Rennes-le-Château, which was also known to the Romans as Aereda.

The inscription on the headstone has many odd features. In the first line, the

i

of

ci

(

ci gît

means “here lies”) has been carved as a capital T. The M of Marie has been left at the end of the first line. The “e” of “noble” is in the lower case. The word following “negre” should read “Dables” not “Darles”, so should have an R, not a B. Altogether there are eight of these anomalies in the inscription, making up two sets of four, one in capital letters and one in lower case. The capitals are TMRO, while the lower case are three e’s and a p. Only one word can be formed of the capitals: MORT – death. Only one word can be formed of the lower-case letters:

epée –

sword. In fact these two words proved to be the “keyword” to decipher the longer of the two parchments found in the pillar . . .

Whether Saunière deciphered it alone, or whether his obliging friends at St Sulpice unknowingly handed him the vital clues, may never be known. All that

is

known is that shortly after this Saunière began spending money at a remarkable rate. He contacted a Paris bank,

who sent a representative to Rennes-le-Château solely to attend to Saunière’s business. Then he built a public road to replace the dirt track that had run to the village, and also had a water supply piped in. He built a pleasant villa with a garden that had fountains and shady walks. To house his library he built a gothic tower perched on the edge of the mountainside. He began to collect rare china, antiques and precious fabrics. He began to entertain distinguished visitors, like Emma Calvé and the Secretary of State for Culture. One of his visitors was recognized as the Archduke Johann von Habsburg, cousin of Franz- Josef, Emperor of Austria. His guests were given the very best of food and wine (and it may be significant that Saunière eventually died of cirrhosis of the liver).

Understandably, Saunière’s superiors were curious about his wealth and wanted to know where it came from. Saunière told them coolly that he was not at liberty to divulge the source of his wealth – some of it came from rich penitents who had sworn him to secrecy. He had also been paid well for saying masses for the souls of the dead. The old bishop decided to mind his own business, but a new one later revealed a pertinacious curiosity, and when Saunière declined to satisfy it, ordered his transfer to another parish. Saunière declined to be transferred. A new priest was appointed to Rennes-le-Château, but the villagers still continued to treat Saunière as their spiritual pastor. Eventually, in 1917, Saunière suffered a stroke, and died at the age of sixty-four. A priest from a neighbouring parish who was called to his deathbed emerged looking pale and shaken, and a local account, doubtless exaggerated, says that he “never smiled again”.

His housekeeper, Marie Denarnaud, lived on until 1953 in considerable affluence. When after the Second World War the French government issued new currency, and demanded to know the source of any large sums (the aim being to trap tax-evaders and profiteers) she burned piles of ten-franc notes in the garden, and lived for the remainder of her life on the proceeds of the sale of Saunière’s villa. She was evidently determined not to betray Saunière’s secret. Just before her death she confided to the purchaser of the villa that she would tell him a secret that would make him both rich and powerful; but she died after a stroke that left her speechless.

The obvious solution to the mystery is that Saunière discovered the treasure mentioned in the parchment, and somehow turned it into modern currency. In which case the mystery is simply what clues he found in the parchment, and how he followed them up to discover the concealed hoard.

Henry Lincoln, a modern investigator, became fascinated by the problem after reading a book called

Le Trésor Maudit

[

The Accursed Treasure

], by Gérard de Sède, in 1969. He made many visits to Rennes-le-Château, and eventually made a programme for BBC television called “The Lost Treasure of Jerusalem . . .?” Lincoln went to Paris to see Gérard de Sède, and before the programme was made de Sède had presented him with the solution of the “long cipher” from the Visigothic column. De Sède claimed that this had been broken with the help of French army experts who had used a computer. Lincoln suspected that this was untrue, and British Intelligence confirmed his suspicion that the code could not have been broken by computer.

The code was unbelievably complex – so complex that Lincoln does not even attempt to explain it in the book he later wrote on the mystery. Cracking it involved a technique known to cipher experts as the Vigenère process, which involves writing out the alphabet twenty-six times in a square, with the first line beginning with A, the second with B, the third with C, and so on. Then the key word Mort Epée is placed over the whole message in this case, of the longer of the two parchments and the letters are transformed by a simple process using the Vigenère table. But the new text is still meaningless. The next step is to move each letter one letter farther down the alphabet. It is still meaningless. The next step is to use a new key word on the jumble. This new key word is the entire text of the headstone beginning “Ci gît noble Maria” etc, and to take from the gravestone the two lots of letters “P.S” and “Prae cum” (Latin for “before” and “with”). This new “keyword” is applied backward to the text, ending with “P.S.” and “Prae cum”. Then all the letters are moved two spaces down the alphabet. Next, the text is divided into two groups of 64, and these are laid out on two chessboards, and the knight makes a series of knight’s moves on the chessboards. Then the letter contained in each square of this series is written down. And now at last the message emerges – although it still looks quite absurd. The message runs:

BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LE CLEF PAX DCLXXXI PAR LA CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU J´ACHEVE CE DAEMON DE GARDIEN A MIDI POMMES BLEUES

. This may be translated:

SHEPHERDESS WITHOUT TEMPTATION TO WHICH POUSSIN AND TENIERS HOLD THE KEY PEACE

681

WITH THE CROSS AND THIS HORSE OF GOD I REACH THIS DAEMON GUARDIAN AT MIDDAY BLUE APPLES

.