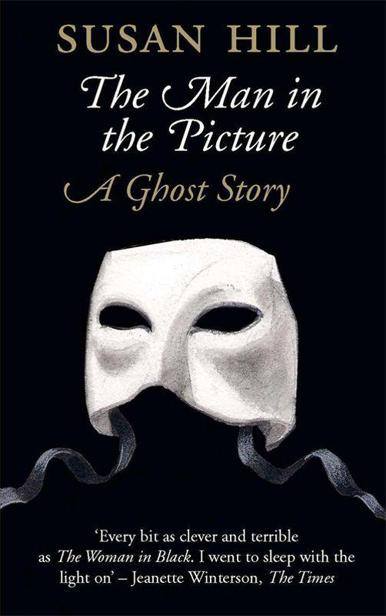

The Man in the Picture

Read The Man in the Picture Online

Authors: Susan Hill

| The Man in the Picture | |

| Susan Hill | |

| Overlook Hardcover (2008) | |

| Rating: | ★★★☆☆ |

Hill (

The Woman in Black

) crafts an old-school spooker in this atmospheric tale of a sinister painting imbued with the vengeful spirit of a former owner. The painting, owned by retired Cambridge don Theo Parmitter, catches the eye of a visiting former student who's intrigued by its depiction of an 18th-century Venetian carnival scene and a figure in the foreground who looks anachronistically modern. The student's questions extract from Theo the strange story of how he won it at auction and the even stranger tale of the bidder he beat: the elderly Lady Hawdon, who claims that the man in the picture is her husband, imprisoned in the painting through the designs of a jilted lover who gave it to them as a wedding present. Hill manipulates the gothic darkness of her story with great dexterity and subtlety, faltering only at its awkwardly executed finish. Regardless, her tale is a commendable exercise in the tradition of the antiquarian ghost story.

(Sept.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

THE MAN

IN THE

PICTURE

Other books by Susan Hill

NOVELS

The Woman in Black

In the Sprngtime of the Year

I’m the King of the Castle

The Bird of Night

SHORT STORIES

The Boy who Taught the Beekeper to read and other Stories

CRIMES NOVELS

The Various Haunts of Men

The Pure in Heart

The Risk of Darkness

THE MAN

IN THE

PICTURE

SUSAN HILL

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

Copyright © Susan Hill, 2007

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Designed in Fournier by Geoff Green Book Design, Cambridge

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978-1-84765-153-2

Stephen Mallatratt

Remembered with love and gratitude

THE MAN

IN THE

PICTURE

CONTENT

HE STORY was told to me by my old tutor, Theo Parmitter, as we sat beside the fire in his college rooms one bitterly cold January night. There were still real fires in those days, the coals brought up by the servant in huge brass scuttles. I had travelled down from London to see my old friend, who was by then well into his eighties, hale and hearty and with a mind as sharp as ever, but crippled by severe arthritis so that he had difficulty leaving his rooms. The college looked after him well. He was one of a dying breed, the old Cambridge bachelor for whom his college was his family. He had lived in this handsome set for over fifty years and he would be content to die here. Meanwhile a number of us, his old pupils from several generations back, made a point of visiting him from time to time, to bring news and a breath of the outside world. For he loved that world. He no longer went out into it much but he loved the gossip – to hear who had got what job, who was succeeding, who was tipped for this or that high office, who was involved in some scandal.

HE STORY was told to me by my old tutor, Theo Parmitter, as we sat beside the fire in his college rooms one bitterly cold January night. There were still real fires in those days, the coals brought up by the servant in huge brass scuttles. I had travelled down from London to see my old friend, who was by then well into his eighties, hale and hearty and with a mind as sharp as ever, but crippled by severe arthritis so that he had difficulty leaving his rooms. The college looked after him well. He was one of a dying breed, the old Cambridge bachelor for whom his college was his family. He had lived in this handsome set for over fifty years and he would be content to die here. Meanwhile a number of us, his old pupils from several generations back, made a point of visiting him from time to time, to bring news and a breath of the outside world. For he loved that world. He no longer went out into it much but he loved the gossip – to hear who had got what job, who was succeeding, who was tipped for this or that high office, who was involved in some scandal.

I had done my best to entertain him most of the afternoon and through dinner, which was served to us in his rooms. I would stay the night, see a couple of other people and take a brisk walk round my old stamping grounds, before returning to London the following day.

But I should not like to give the impression that this was a sympathy visit to an old man from whom I gained little in return. On the contrary, Theo was tremendous company, witty, acerbic, shrewd, a fund of stories which were not merely the rambling reminiscences of an old man. He was a wonderful conversationalist – people, even the youngest Fellows, had always vied to sit next to him at dinner in hall.

Now, it was the last week of the vacation and the college was quiet. We had eaten a good dinner, drunk a bottle of good claret, and we were stretched out comfortably in our chairs before a good fire. But the winter wind, coming as always straight off the Fens, howled round and occasionally a burst of hail rattled against the glass.

Our talk had been winding down gently for the past hour. I had told all my news, we had set the world to rights between us, and now, with the fire blazing up, the edge of our conversation had blunted. It was delightfully cozy sitting in the pools of light from a couple of lamps and for a few moments I had fancied that Theo was dozing.

But then he said, ‘I wonder if you would care to hear a strange story?’

‘Very much.’

‘Strange and somewhat disturbing.’ He shifted in his chair. He never complained of it but I suspected that the arthritis gave him considerable pain.

‘The right sort of tale for such a night.’

I glanced across at him. His face, caught in the flicker of the firelight, had an expression so serious – I would almost say deathly serious – that I was startled. ‘Make of it what you will, Oliver,’ he said quietly, ‘but I assure you of this, the story is true.’ He leaned forward. ‘Before I begin, could I trouble you to fetch the whisky decanter nearer?’

I got up and went to the shelf of drinks, and as I did so, Theo said, ‘My story concerns the picture to your left. Do you remember it at all?’

He was indicating a narrow strip of wall between two bookcases. It was in heavy shadow. Theo had always been known as something of a shrewd art collector with some quite valuable old-master drawings and eighteenth-century water-colours, all picked, he had once told me, for modest sums when he was a young man. I do not know much about paintings, and his taste was not really mine. But I went over to the picture he was pointing out.

‘Switch on the lamp there.’

Although it was a somewhat dark oil painting, I now saw it quite well and looked at it with interest. It was of a Venetian carnival scene. On a landing stage beside the Grand Canal and in the square behind it, a crowd in masks and cloaks milled around among entertainers – jugglers and tumblers and musicians and more people were climbing into gondolas, others already out on the water, the boats bunched together, with the gondoliers clashing poles. The picture was typical of those whose scenes are lit by flares and torches which throw an uncanny glow here and there, illuminating faces and patches of bright clothing and the silver ripples on the water, leaving other parts in deep shadow. I thought it had an artificial air but it was certainly an accomplished work, at least to my inexpert eye.

I switched off the lamp and the picture, with its slightly sinister revellers, retreated into its corner of darkness again.

‘I don’t think I ever took any notice of it before,’ I said now, pouring myself a whisky. ‘Have you had it long?’

‘Longer than I have had the right to it.’

Theo leaned back into his deep chair so that he too was now in shadow. ‘It will be a relief to tell someone. I have never done so and it has been a burden. Perhaps you would not mind taking a share of the load?’

I had never heard him speak in this way, never known him sound so deathly serious, but of course I did not hesitate to say that I would do anything he wished, never imagining what taking, as he called it, ‘a share of the load’ would cost me.