The Man Who Sold the World

Read The Man Who Sold the World Online

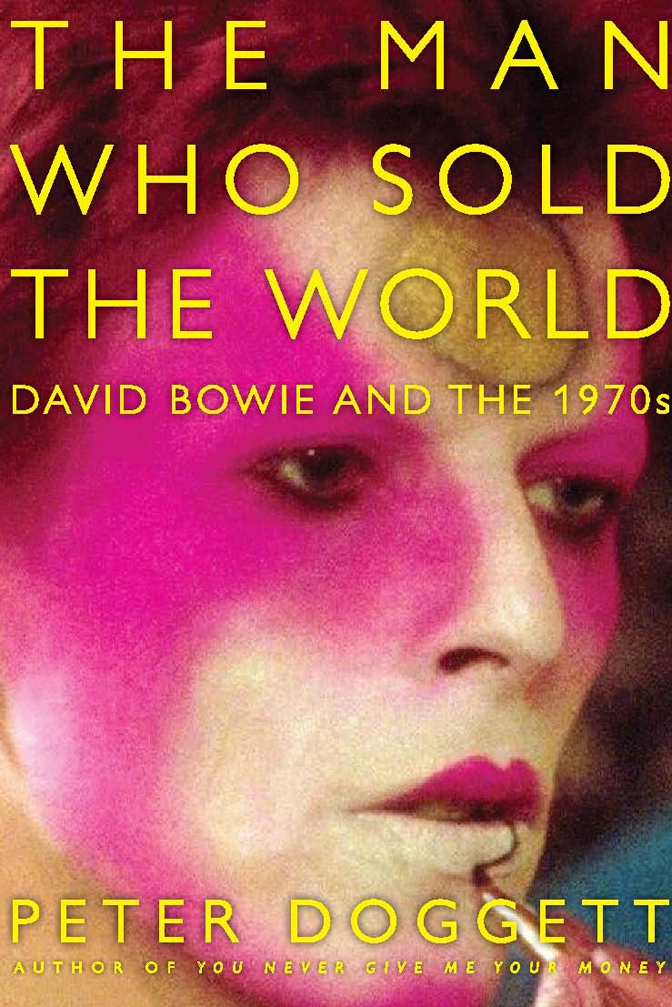

Authors: Peter Doggett

THE MAN WHO SOLD THE WORLD

DAVID BOWIE AND THE 1970S

PETER DOGGETT

CONTENTS

Â

THE MAKING OF DAVID BOWIE: 1947â1968

THE SONGS OF DAVID BOWIE: 1969â1980

Â

ESSAYS:

SOUND AND VISION #1:

LOVE YOU TILL TUESDAY

THE MAKING OF A STAR #1: ARNOLD CORNS

ANDY WARHOL: POP TO

PORK

AND BACK AGAIN

THE MAKING OF A STAR #2: THE BIRTH OF ZIGGY STARDUST

THE MAKING OF A STAR #3:

THE RISE AND FALL OF ZIGGY STARDUST AND THE SPIDERS FROM MARS LP

TRANSFORMER

: BOWIE AND LOU REED

THE UNMAKING OF A STAR #1: ROCK 'N' ROLL SUICIDE

SIXTIES NOSTALGIA AND MYTH:

PIN UPS

LP

THE UNMAKING OF A STAR #2:

DAVID LIVE

LP

SOUND AND VISION #2:

THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH

THE UNMAKING OF A STAR #3: COCAINE AND THE KABBALAH

THE ACTOR AND THE IDIOT: BOWIE AND IGGY

SOUND AND VISION #3:

JUST A GIGOLO

SCARY MONSTERS (AND SUPER CREEPS)

LP

SOUND AND VISION #4: A NEW CAREER IN A NEW MEDIUM

APPENDIX: THE SONGS OF DAVID BOWIE: 1963â1968

Â

There have been numerous biographies of David Bowie, but never before a book that explains how he emerged as the most vital and influential pop artist of the 1970s, or identifies the full depth and implications of his achievements.

The Man Who Sold the World

is intended to fill that gap, with a detailed examination of the man, the work, and the culture beyond.

After an initial study of how the David Jones who was born in 1947, and who struggled through the 1960s, was transformed into the David Bowie who shaped the 1970s,

The Man Who Sold the World

is focused squarely on the songs in which he reflected his times, and expressed his unique personality. Indeed, the book includes an entry on every song he wrote and/or recorded during that decadeâthe “long” seventies, as I call it, running from 1969 to 1980, and from “Space Oddity” to its sequel, “Ashes to Ashes.” These entries make up the bulk of the text, with each song numbered (in square brackets, from 1 to 189) in chronological order of composition. (When that information isn't available, as with all of Bowie's albums after 1975, the songs are covered in the sequence in which they appear on those records. The songs he wrote and recorded between 1963 and 1968 can be found in the appendix, and are numbered A1âA55.)

Interspersed at appropriate points among those song-by-song studies are reviews of every commercial project (albums and films) that Bowie undertook during this time frame and short essays on the major themes in his work and times, from the occult to glam rock, and fashion to fascism. Together, these elements build up a chronological portrait of an artist who set out to explore all the possibilities and repercussions of fragmentation during this eraâartistic, psychological, and cultural.

The unabashed model for

The Man Who Sold the World

is

Revolution in the Head

, the pioneering study of the Beatles' songs against the backdrop of the sixties, by the late British journalist Ian MacDonald. At the time of his death, MacDonald was under commission to write a similar book about Bowie and the seventies, and his UK editor invited me to pick up the torch. MacDonald was a trained musicologist, and

Revolution in the Head

sometimes tested the understanding of anyone who lacked his grounding in musical theory. I have chosen to take more of a layman's path through Bowie's music, assuming only a limited knowledge of musical terminology, and the ability to grasp how (for example) a change from minor to major chords in a song can alter not only the notes that Bowie plays and sings, but the emotional impact that those notes have on the listener. I have used abbreviations for chordsâ

Am

for A minor, etc.âthat will be familiar to anyone who has ever strummed a guitar. On a few occasions, I have also employed the Roman numeral system of denoting chords within a particular key. I-vi-IV-V, for example, refers to a chord sequence that begins with the tonic or root chord of the key, moves to a minor sixth (minor denoted by being in lowercase), then a major fourth and major fifth. In this instance, the sequence denotes a series of chords that will be instantly recognizable to anyone who has ever heard 1950s doo-wop music: in the key of C major, it equates to a sequence of C-Am-F-G.

Musicology aside, I have employed the widest possible parameters for my critiques of each song: examining the words, the music, how they fit together, how they are performed, how they affect the audience, what they represent in Bowie's career, what they tell us about the wider culture, and what influenced him to create them. The result is a book that examines David Bowie the artist, rather than the celebrity, and helps to explain the significance of a song catalogue that is as revealing a guide to the seventies as the Beatles' music was to the sixties.

Early in this project, I realized that every Bowie fan carries a different version of the artist in his or her heart. His career has been so eclectic and multifaceted that it can support multiple interpretations. This is, unashamedly, mineâthe work of someone whose relationship with Bowie's music has undergone almost as many changes over the past forty years as the man himself. During that time, there have certainly been periods (much of the eighties, for example) when I felt that each new, and disappointing, manifestation of Bowie's career ate away at the luster of what had gone before. Then, as the nineties progressed, it became obvious that Bowie had succeeded in reconnecting with his artistic selves and compressing them into work that may not have been as radical as the peaks of his seventies catalogue, but still demonstrated a fierce critical intelligence alongside his enduring musical skills.

Writing this book has allowed me the delightful indulgence of being able to study a collection of music that bears comparison with any comparable catalogue within the very broad remit of popular entertainment. I have been thrilled by Bowie's versatility, touched by his emotional commitment, and most of all, stunned by the daring with which he approached a genre (rock, in its broadest sense) that was becoming increasingly conformist during the course of the seventies. At a time when pop artists are encouraged to repeat themselves endlessly within crushingly narrow margins, his breadth of vision and sense of adventure remain truly inspiring.

PEOPLE LOOK TO ME TO SEE WHAT THE SPIRIT OF THE 70S IS, AT LEAST, 50% OF THEM DOâCRITICS I DON'T UNDERSTAND. THEY GET TOO INTELLECTUAL.

Â

âDavid Bowie, 1973

Â

I

Historians often prefer to ignore the rigid structure of the calendar and define their own decades. These can be “short” or “long,” lasting six years or sixteen: for example, the “short” sixties might be bracketed by the impact of Beatlemania in 1963 and the Manson murders in 1969; their “long” equivalent could stretch from Harold Macmillan's “never had it so good” speech in 1957 to America's withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973. What unifies these artificial eras is a sense of identity that marks them out from what came before and after.

Perhaps anticipating that the seventies might be less susceptible to easy categorization than its overmythologized predecessor, David Bowie effectively imposed his own “long” margins on the decade. At the start of 1969, he wrote “Space Oddity” [1], a song that punctured the global admiration for the Apollo mission to the moon. His hero, Major Tom, was not making a giant leap for mankind, but sitting in the alienated exile of a lunar capsule, unwilling to come back to earth. In 1980, Bowie returned to the scenario of that song in “Ashes to Ashes” [184], to discover that his reluctant hero was still adrift from humanity, as if the previous eleven years had changed nothing. “Space Oddity” turned David Bowie into an uneasy pop star; “Ashes to Ashes” marked the end of his long decade of stardom, during which he had tested the culture, and his own personality, to the limits of their fragile endurance.

Like the Beatles in the decade before him, Bowie was popular culture's most reliable guide to the fever of the seventies. The Beatles' lives and music had reflected a series of shifts and surges in the mood of their generation, through youthful exuberance, satirical mischievousness, spiritual and chemical exploration, political and cultural dissent, and finally depression and fragmentation. The decade of David Bowie was altogether more challenging to track. It was fired not by idealism or optimism but by dread and misgiving. Perhaps because the sixties had felt like an era of progress, the seventies was a time of stasis, of dead ends and power failures, of reckless hedonism and sharp reprisals. The words that haunted the culture were

decline

,

depression

,

despair

: the energy of society was running out, literally (as environmentalists proclaimed the imminent exhaustion of fossil fuel supplies) and metaphorically. By the decade's end, cultural commentators were already defining the era in strictly negative terms: the chief characteristic of the seventies was that it was not what the prime movers of the sixties had hoped it would be.

This was not, at first sight, the stuff of pop stardom. The Beatles would have struggled to capture the hearts of their generation had they preached a message of conflict and decay, rather than idealism and love. What enabled David Bowie to reflect the fear and chaos of the new decade was precisely the fact that he had been so out of tune with the sixties. He was one of the first pop commentators to complain that the optimism that enraptured the youth of the West in the mid-sixties was hollow and illusory. His negativity seemed anachronistic, but it merely anticipated the realization that Western society could not fuel and satisfy the optimism of sixties youth culture. “Space Oddity” aside, his work of 1969â70 failed to reach the mass audience who heard the Rolling Stones'

Let It Bleed

or John Lennon's

Plastic Ono Band

, two albums that also tore away the pretensions of the recent past. But even those records paled alongside the nihilistic determinism of Bowie's first two albums in his new guise as cultural prophet and doom-monger.

Bowie might have maintained a fashionable gloom for the next decade, and turned his sourness into a calling. Instead he embarked on a far more risky and ambitious course. Unable to secure a mass audience for his explorations of a society in the process of fragmentation, he decided to create an imaginary hero who could entrance and then educate the pop audienceâand to play the leading role himself. Since the start of his professional career as an entertainer in 1964, he had used his brief experience as a visualizer in an advertising agency to rebrand himself in a dozen different disguises. Now he would concentrate on a single product and establish a brand so powerful that it would be impossible to ignore. The creation of Ziggy Stardust in 1972 amounted to a conceptual art statement: rather than pursuing fame, as he had in the past, Bowie would act as if he were already famous beyond dispute, and present himself to the masses as an exotic creature from another planet. Ziggy would live outside the norms of earthly society: he would be male and female, gay and straight, human and alien, an eternal outsider who could act as a beacon for anyone who felt ostracized from the world around them. Aimed at a generation of adolescents emerging into an unsettling and fearful world, his hero could not help but become a superstar. Whereupon Bowie removed him from circulation, destroying the illusion that had made him famous.

What happened next was what made Bowie not just a canny manipulator of pop tastes, but a significant and enduring figure in twentieth-century popular culture. He channeled the momentum of Ziggy Stardust's twelve months of fame into a series of artistic and psychological experiments that tugged at the margins of popular entertainment, and at the cohesion of his own psyche. Between 1974 and 1980, Bowie effectively withdrew from the world around him and created his own microcultureâa bewildering landscape in which nothing was fixed and everything familiar was certain to change shape before the observer's eyes.

Bowie's methods were simple, and devastating: he placed himself into alien environments and cultures (New York, Los Angeles, Berlin; R&B music, experimental rock, ambient soundscapes), turned them to his own devices, and then systematically demolished what he had just created. In each situation, he pushed himself, and his surroundings, to their limits, to see whether they would crack or bend. Then he moved on, relentlessly and compulsively, to the next incarnation. Ultimately he succeeded in shedding all the skins and disguises he had worn since 1964, and all of the cultural debris, to arrive in 1980: enervated, disgusted, exhausted, free. Then he, like Ziggy Stardust, disappeared.

What linked the sounds of the seventies, Bowie once said, was irony, and there was irony aplenty when he chose to reappear in 1983ânot as a restless investigator of fresh cultures and techniques, but as nothing more disruptive than the professional entertainer who had been hiding beneath his skins from the beginning. The irony was that his audience was so desperate to believe he was still the David Bowie of 1972, 1976, or 1980 that they ignored his artistic inertia and greeted him as a conquering heroâBowie therefore becoming exactly the mainstream success that he had parodied in the seventies. Only in the nineties did his work rekindle the spirit of more interesting times; by then the world at large was interested in Bowie only as a figure of nostalgia, not as a creative artist. But that is another story.

Â

II

Fragmentation was central to Bowie's seventies. He pursued it in artistic terms by applying cut-up techniques to his language, subverting musical expectations, employing noise as a way of augmenting and substituting for melody, using a familiar formula and distorting it into an alarming new shape. He applied the same tools to his identities and images, assembling each different persona from the remnants of the past.

Even Ziggy Stardust, the guise in which Bowie left his most enduring mark on the decade, was assembled like a collage from a bewildering variety of sources, despite his appearance of having stepped fully formed from a passing flying saucer. Elements of Ziggy came from pop: from Judy Garland, the Rolling Stones, the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, the Beatles, Elvis Presley, Little Richard. Strands of Pop Art were also visible in Ziggy's disguise, from Richard Hamilton's assimilation of science fact and science fiction to Andy Warhol's obsession with surface and the borrowed sheen of stardom. Through Ziggy, Bowie was also able to access themes that preoccupied the wider culture: the ominous hum of apocalypse, the fear of decay, the compulsive attraction of power and leadership, the search for renewed belief in a time of disillusion. Ziggy represented the “over-man” that Bowie had discovered in the writings of Nietzsche; the Fuhrer who had commanded magnetic attention in Germany; the pop icons who had peopled Bowie's own dreams; the struggle of Western civilization to adjust to a world order that had slipped beyond its control.

Yet fragmentation wasn't just an artistic technique for Bowie: it became the only way in which he could transcend his own psychological heritage. He was born into a family web of mental instability, frustrated ambition, and emotional repression. In his teens, he had become aware that authentic emotional responses could not always be controlled; that self-expression could carry someone beyond the acceptable borders of sanity. He had always imagined that success would offer him stability; that he could only become himself in the eyes of an audience; and to achieve that aim, he was prepared to unmake and remake his identity as often and as radically as he needed to.

This fluid sense of the self was what enabled him to explore such varied terrain, as an artist and a human being. The pioneering psychologist William James once recounted his own unmaking of identity: “It consisted in a gradual but swiftly progressive obliteration of space, time, sensation and the multitudinous factors of experience which seem to qualify what we are pleased to call our Self.” He described this process as “mysticism”; and in his exploration of Buddhist meditation in the late sixties, Bowie would have arrived at a similar sense of what psychologists call “undifferentiation.” As the seventies progressed, he explored a variety of ways of achieving this state. The most commonplace, for a rock star of his era, was through drugs, which inflated his ego, fueled his restless creativity, and threw his senses into disarray. From his complex family background came the tantalizing, terrifying notion that madnessâpsychosis, schizophreniaâmight be a means of establishing his identity, and destroying it in the same moment. He spent a decade trying to avoid what his grandmother called the family curse, and then several more years creating his own form of psychosis with cocaine and amphetamines.

In place of Buddhist meditation, he became obsessed in the seventies with the exploration of the occult: the search for hidden powers and meanings, the attempt to reach beyond the conscious into a realm of unimaginable riches and danger. And it was that quest for something beyond that also inspired his artistic experiments, encouraging him to reach through or around familiar techniques to access material and methods that would help him to overcome the limitations and repressions of the everyday world around him. He would use erratic combinations of all four methods of escapeâhallucination, meditation, madness, innovationâthroughout the seventies, taking fearful risks with his health and sanity, sabotaging key personal relationships, and creating a body of work that surpassed anything in rock for its eclecticism and sense of daring.

Â

III

“This is a mad planet,” Bowie said in 1971. “It's doomed to madness.” Or, as novelist William S. Burroughs had written four years earlier: “abandon all nations, the planet drifts to random insect doom.”

Since the late sixties, the notion that mankind was facing apocalyptic disaster had begun to infect every vein of Western society. Cultural critic Susan Sontag noted that the awareness of fear created its own reality: “Collective nightmares cannot be banished by demonstrating that they are, intellectually and morally, fallacious.” The global bestseller of the early 1970s was Hal Lindsey's recklessly naïve

The Late Great Planet Earth

, which twisted the Christian scriptures to suggest that apocalypse would soon emerge from the Middle East. Lindsey's book was no more rational than thousands of similar explorations of religious paranoia that had been published down the centuries, but it had found its perfect moment. Its alarmist arguments resonated through the popular press and prepared the ground for the ultraconservative brand of evangelical Christianity that would help to propel Ronald Reagan into the White House a decade later.

If Hal Lindsey's dread was superstitious, it chimed with the sobering warnings of the scientists who predicted environmental disaster for mankind. The debate had been simmering since the early 1960s, erupting into mainstream culture in the form of tabloid headlines or science fiction dystopias. The threats were so immenseâa new ice age, global warming, mass starvation, the exhaustion of water, food, or fuelâthat it was easier to ignore them than tackle them. They merged seamlessly into the recurrent fear of global annihilation via nuclear warfare, meeting on the equally uncertain ground of nuclear power. As if to signal that the new decade would force these environmental monsters into our everyday lives, the BBC launched a television series in February 1970 called

Doomwatch

, about a governmental department whose brief was nothing less than the preservation of mankind against overwhelming natural (and extraterrestrial) threats. Hollywood extended the theme with the disaster movies that captured the popular imagination for much of the decade.

In the teeth of

Jaws

and

The Towering Inferno

, there was something intolerably mundane about financial catastrophe and the pervasive sense of decline that afflicted the West (and particularly Britain) through the early seventies. Successive leaders had been preaching economic doom since the mid-sixties, to the point where the pronouncement in late 1973 that Britain was facing its gravest economic crisis since the end of World War II sounded almost comfortingly familiar. Industrial unrest triggered strike action among key workers, and periodically during the decade, the British population was returned to the age of candlelight, as regular power cuts restricted television broadcasts, closed cinemas, darkened neon advertising displays, canceled sporting events, and of course deprived homes and offices of light, warmth, and electricity. These episodes occupied no more than a few weeks of the decade, but they left such a mark that they remain the dominant folk memory of the 1970s.