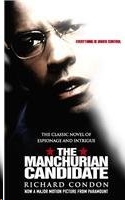

The Manchurian Candidate

Read The Manchurian Candidate Online

Authors: Richard Condon

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrillers, #Espionage, #Military, #Suspense

Praise for Richard Condon and one of the

most electrifying novels of international

espionage and treachery ever written…

THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE

“SHOCKING, TENSE…. A HIGH-GRADE ADVENTURE-SUSPENSE.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“APOCALYPTIC…CONDON IS WICKEDLY SKILLFUL.”

—Time

“ORIGINAL…A BREATHLESSLY UP-TO-DATE THRILLER.”

—The New York Times

“SAVAGE…. FRIGHTENING…. EXTRAORDINARY.”

—Kirkus Reviews

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

A Pocket Star Book published by

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 1959 by Richard Condon

Copyright renewed © 1987 by Richard Condon

Cover art copyright © 2004 Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN-13: 978-0-7434-9274-4

ISBN-10: 0-7434-9274-9

POCKET STAR BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

To MAX YOUNGSTEIN,

and not only for reasons

of affection and admiration,

this book is warmly dedicated.

The order of Assassins was founded in Persia at the end of the 11th century. They were committed to anyone willing to pay for the service. Assassins were skeptical of the existence of God and believed that the world of the mind came into existence first, then, finally, the rest of creation.

—

Standard Dictionary of

Folklore, Mythology and Legend

I am you and you are me and what have we done to each other?

—

The Keener’s Manual

One

IT WAS SUNNY IN SAN FRANCISCO; A FABULOUS

condition. Raymond Shaw was not unaware of the beauty outside the hotel window, across from a mansion on the top of a hill, but he clutched the telephone like an

osculatorium

and did not allow himself to think about what lay beyond that instant: in a saloon someplace, in a different bed, or anywhere.

His lumpy sergeant’s uniform was heaped on a chair. He stretched out on the rented bed, wearing a new one-hundred-and-twenty-dollar dark blue dressing gown, and waited for the telephone operator to complete the chain of calls to locate Ed Mavole’s father, somewhere in St. Louis.

He knew he was doing the wrong thing. Two years of Korean duty were three days behind him and, at the very least, he should be spending his money on a taxicab to go up and down those hills in the sunshine, but he decided his mind must be bent or that h

e was drunk with compassion, or something else improbable like that. Of all of the fathers of all of the fallen whom he had to call, owing to his endemic mopery, this one had to work nights, because, by now, it must be dark in St. Louis.

He listened to the operator get through to the switchboard at the

Post-Dispatch.

He heard the switchboard tell her that Mavole’s father worked in the composing room. A man talked to a woman; there was silence. Raymond stared at his own large toe.

“Hello?” A very high voice.

“Mr. Arthur Mavole, please. Long distance calling.” The steady rumble of working presses filled the background.

“This is him.”

“Mr. Arthur Mavole?”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“Go ahead, please.”

“Uh—hello? Mr. Mavole? This is Sergeant Shaw. I’m calling from San Francisco. I—uh—I was in Eddie’s outfit, Mr. Mavole.”

“My Ed’s outfit?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ray Shaw?”

“Yes, sir.”

“The Ray Shaw? Who won the Medal of—”

“Yes, sir.” Raymond cut him off in a louder voice. He felt like dropping the phone, the call, and the whole soggy, masochistic, suicidal thing in the wastebasket. Better yet, he should whack himself over the head with the goddam phone. “You see, uh, Mr. Mavole, I have to, uh, go to Washington, and I—”

“We know. We read all about it and let me say with all my heart I got left that I am as proud of yo

u, even though I never met you, as if it were Eddie, my own kid. My son.”

“Mr. Mavole,” Raymond said rapidly, “I thought that if it was O.K. with you maybe I could stop over in St. Louis on my way to Washington, you know? I thought, I mean it occurred to me that you and Mrs. Mavole might get some kind of peace out of it, some kind of relief, if we talked a little bit. About Eddie. You know? I mean I thought that was the least I could do.”

There was a silence. Then Mr. Mavole began to make a lot of slobbering sounds so Raymond said roughly that he would wire when he knew what flight he would be on and he hung up the phone and felt like an idiot. Like an angry man with a cane who pokes a hole through the floor of heaven and is scalded by the joy that pours down upon him, Raymond had a capacity for using satisfactions against himself.

When he got off the plane at St. Louis airport he felt like running. He decided Mavole’s father must be that midget with the eyeglasses like milk-bottle bottoms who was enjoying sweating so much. The man would be all over him like a charging elk in a minute. “Hold it! Hold it!” the pimply press photographer said loudly.

“Put it down,” Raymond snarled in a voice which was even more unpleasant than his normal voice. All at once the photographer was less sure of himself. “Whassa matter?” he asked in bewilderment—because he lived at a time when only sex criminals and dope peddlers tried to refuse to have their pictures taken by the press.

“I flew all the way in here to see Ed Mavole’s father,” Raymond said, despising himself for throwing up such corn. “You want a picture, go find him, because you ain’t gonna take one of me without he’s in it.”

Listen to that genuine, bluff sergeant version of

police verso,

Raymond cried out to himself. I am playing the authentic war buddy so deeply that I will have to mail in a royalty check for the stock rights. Look at that clown of a photographer trying to cope with phenomena. Any minute now he will realize that he is standing right beside Mavole’s father.

“Oh, Sergeant!” the girl said, so then he knew who

she

was. She wasn’t red-eyed and runny-nosed with grief for the dead hero, so she had to be the cub reporter who had been assigned to write the big local angle on the White House and the Hero, and he had probably written the lead for her with that sappy grandstand play.

“I’m Ed’s father,” the sweat manufacturer said. It was December, fuh gossake, what’s with all the dew? “I’m Arthur Mavole. I’m sorry about this. I just happened to mention at the paper that you had called all the way from San Francisco and that you had offered to stop over and see Eddie’s mother on the way to the White House, and the word somehow got upstairs to the city desk and well—that’s the newspaper business, I guess.”

Raymond took three steps forward, grasped Mr. Mavole’s hand, gripped his right forearm with his own left hand, transmitted the steely glance and the iron stare and the frozen fix. He felt like Captain Idiot in one of those space comic books, and the photographer got the picture and lost all interest in them.

“May I ask how old you are, Sergeant Shaw?” the young chick said, notebook ready, pencil poised as though she and Mavole were about to give him a fitting, and he figured reflexively that this could be the first assignment she had ever gotten after years of journalism school and months of social notes f

rom all over. He remembered his first assignment and how he had feared the waffle-faced movie actor who had opened the door of the hotel suite wearing only pajama bottoms, with corny tattoos like So Long, Mabel on each shoulder. Inside the suite Raymond had managed to convey that he would just as soon have hit the man as talk to him and he had said, “Gimme the handout and we can save some time.” The traveling press agent with the actor, a plump, bloodshot type whose glasses kept sliding down his nose, had said, “What handout?” He had snarled that maybe they would prefer it if he started out by asking what was the great man’s hobby and what astrology sign he had been born under. It was hard to believe but that man’s face had been as pocked and welted as a waffle, yet he was one of the biggest names in the business, which gives an idea what those swine will do to kid the jerky public. The actor had said, “Are you scared, kid?” Then, after that, everything seemed to go O.K. They got along like a bucket of chums. The point was, everybody had to start someplace.

Although he felt like a slob himself for doing it, he asked Mr. Mavole and the girl if they would have time to have a cup of coffee at the airport restaurant because he was a newspaperman himself and he knew that the little lady had a story to get. The little lady? That was overdoing it. He’d have to find a mirror and see if he had a wing collar on.

“You were?” the girl said. “Oh, Sergeant!” Mr. Mavole said a cup of coffee would be fine with him, so they went inside.

They sat down at a table in the coffee shop. The windows were steamy. Business was very quiet and unfortunately the waitress seemed to have nothing

but time. They all ordered coffee and Raymond thought he’d like to have a piece of pie but he could not bring himself to decide what kind of pie. Did everybody have to look at him as though he were sick because he couldn’t set his taste buds in advance to be able to figure which flavor he would favor before he tasted it? Did the waitress just have to start out to recite “We have peach pie, and pumpk—” and they’d just yell out Peach, peach, peach? What was the sense of eating in a place where they gabbled the menu at you, anyway? If a man were intelligent and he sorted through the memories of past tastes he not only could get exactly what he wanted sensually and with a flavor sensation, but he would probably be choosing something so chemically exact that it would benefit his entire body. But how could anyone achieve such a considerate deliberate result as that unless one were permitted to pore over a written menu?

“The prune pie is very good, sir,” the waitress said. He told her he’d take the prune pie and he hated her in a hot, resentful flash because he did not want prune pie. He hated prune pie and he had been maneuvered into ordering prune pie by a rube waitress who would probably slobber all over his shoes for a quarter tip.