The Margarets (2 page)

Authors: Sheri S. Tepper

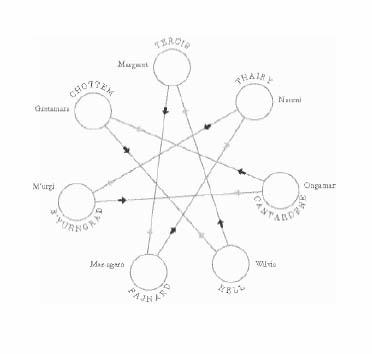

Mercan Combine: Confederation of vile races united by proximity, race, language, commerce

Omniont Federation: Similar to the Mercan Combine, but less cutthroat and more concerned with ethics

Dominion Central Authority: Oversight body set up by the Gentherans to represent off-Earth humans

Once a very long time ago, between fifty and a hundred thousand years, a small group of humans fleeing from predators took refuge in a cave. Clinging to one another during the night, they heard a great roaring, louder and more fierce than the roars of the beasts they knew, and when they peeked out at dawn, they saw that a moon had fallen out of the sky. The sun was just rising, the changeable baby moon they were used to was with Mother Sun, so the fallen moon belonged to someone else.

The someone elses were walking here and there, clanking and creaking. Ahn, the leader of the people, noticed holes around the bottom of the moon, open holes as large as caves. The clanking things were frightening, but not so scary as the animals howling among the nearest trees. Ahn, the leader, had no memory of such things; neither did any of the other of his people. No clanking things. No falling moons.

Ahn nodded, thoughtfully. It was harder when it was a new thing. If they had a memory of the thing, it was easier to figure out what to do. Otherwise, they had to decide, then see what would happen. It did seem to Ahn, however, that hiding inside the moon was a good idea. When the moon went back up into the sky, the beasts couldn’t follow. The holes smelled strange, so Ahn went first in case there were bad things inside.

Just as there had been no memory of fallen moons, there had been no memory of those who owned the moon: the Quaatar, who disliked being fooled with, bothered by, or trespassed upon by anything. Even if Ahn had had such a memory, the immediacy of his people’s situation might have made him risk it. Since he did not know it, he had no qualms about leading his people up the vent tubes and thence into a hydroponic oasis.

The ship’s robots found nothing worth ravening upon the world; the ship departed. Inside, the stowaways lived rather pleasantly on the juicy bodies of small furry vermin that infested the ship and the garden produce that fed the noncarnivorous creatures aboard. When the ship finally landed, the people went out to find themselves not in the sky, as they had expected, but rather upon some other world, where their eager senses informed them there were no predators at all. The world was a paradise, and they fled into it.

Ahn’s people never knew how they got there; the Quaatar were and are a little-known people. The females are said to be solitary, aquatic, and planet-bound. The males return to the water only to breed. It is said if one imagines a huge, multilegged lizard, hundreds of years old, who is able to talk and count from one to six, one has imagined a Quaatar. The race became starfaring only by accident. Early in their evolutionary history, they were approached by an advanced people who offered to trade for mining rights on the several lifeless, metal-rich planets of the system. Galactic Law required that they need deal only with the most numerous indigenous group. The Quaatar demanded first that three lesser tribes, the Thongal, Frossians, and K’Famir, who had long ago branched treacherously from the Quaatar genetic line, be wiped out. Since Galactic Law did not permit such a thing, the mining concessionaires offered many other inducements, finally agreeing, among other things, to move the other tribes or races far away. The Thongal, Frossians, and K’Famir, all of whom were more agile and far cleverer than the Quaatar, had no objection at all to being removed from the dismal swamps of Quaatar and given drier planets of their own. They were accordingly transported, leaving the Quaatar alone and unchallenged in their insistence that themselves, their world, and their language were sacred and inviolable.

For generations the Quaatar traded mining rights for fancy uniforms, medals, starships, and spare parts plus an endless supply of non-Quaatar mechs, techs, and astrogators to keep the ships flying. Though Quaatar owned the ships and appropriated all the fancy titles (captain, chief science officer, and so on), they never learned how to go from point A to point B without relying on non-Quaatar crew members who could count much higher than six to take them there.

The Quaatar had not known they had stowaways until they saw Ahn’s people leaving the ship and disappearing into the underbrush. The sight infuriated them. It should be mentioned that an infuriated Quaatar is something no reasonable individual wants to deal with. An aroused Quaatar is somewhat comparable to a tsunami engendered by an earthquake measuring eight or nine on the Richter scale while several supervolcanoes erupt simultaneously during a category five hurricane. The Quaatar ordered the ship to destroy the planet and were dissuaded only when the automatic system governor harshly reminded them the Galactic Court would not allow destruction of living planets.

Quaatar annoyance, once aroused, however, had to be slaked, not least because their vessel, sacred to the holy Quaatar race, had been defiled and would have to be resanctified. All non-Quaatar personnel were sequestered, for their own safety, while every deck was washed down with the blood of sacrificial victims (a supply of whom were always carried on Quaatar ships), who were first flayed to yield skins with which the entire exterior hull had to be scrubbed. Finally, skin, bones, and remaining tissue were ritually burned. This was time-consuming, yielding only mild amusement during the flaying part, and it was all the fault of the stowaways.

When the ritual was completed, the Quaatar turned their attention back to vengeance. Honor demanded that revenge be exacted upon those who had committed the trespass. Since the Quaatar could not find the beings who had fled the ship, they decided to maim them from a distance by using a recently and illicitly obtained brain block ray, which could be set to atrophy parts of the brain of any animal that had one. Since they had no sample stowaway to set the machine with (and would have been unlikely to do it correctly had they had one), they entered an arbitrary and random setting, trusting that

their god, Dweller in Pain, who had been properly propitiated, would see to the seemliness of the punishment.

Accordingly, the stowaways’ brains were fried. This left untouched the race from which they had come, which was equally guilty since it had produced the offenders. The Quaatar “captain” ordered the ship to be returned to the penultimate planet, where the brain block ray, still on the same setting, was set to cover the entire surface of the world during one complete revolution.

When the Quaatar departed, they left monitors behind to send images they later watched with great gratification as several generations of the creatures struggled to compensate for their new handicap. The ray had not made them completely mindless. It had merely wiped out the memory of certain things. This loss was a considerable handicap, however, and by the time several generations had passed, there were only fifteen or twenty thousand of them left.

“Can they ever get it back?” a junior Quaatar asked its elder. Very young Quaatar sometimes had ideas, before their brains solidified.

The senior drew itself up pompously. “There is no it! The it no longer exists!”

“Legend says everything exists, you know, where Keeper keeps everything.”

“Tah. Is dirty K’Famir legend! If kept, is in a place these filth could never find, never!”

“Somebody says Pthas did.”

“Tss,” the senior sneered. “Dirty K’Famir legend says Pthas went many places nobody wanted them. K’Famir say Keeper much annoyed by visit of Pthas. K’Famir say Keeper changed rules, told Pthas only person walking seven roads at once can ever see Keeper. That is like saying nobody, never. That is good thing. Seven is unlucky for Quaatar. Six is enough number.”

“If something had seven all-same-time universes, it could…”

“Enough!” roared the senior. “You are bad-lucking us with utterance? You want go in hold with sacrifices? You want skinning?”

The junior member tardily, wisely, kept silent.

Before continuing their journey, the Quaatar celebrated by torturing several of the non-Quaatar crew members, whose families later received the generous life insurance payments that had been guaran

teed by the mining interests before the crew members could have been ordered onto the Quaatar vessel. Thereafter the Quaatar often talked about their vengeance with others of their kind, though always without mentioning the return to the planet of origin or the use to which certain crew members had been put. The return had not been approved by the chiefs of Quaatar, and both the torture of crew members and the use of the brain block was specifically forbidden by the Galactic Court, a body greatly feared though not at all respected by the Quaatar.

In time the Quaatar crew died, those with whom they had spoken died, and nothing about the happening was remembered except the prejudice that had been engendered against a race of bipedal, naked, rather ugly creatures, forever anathema to the Quaatar. The bipeds were Crnk-cha zibitzi, that is half-brained defilers, which was the worst thing they could have been. When humans finally made it off their home planet, the Quaatar greeted their appearance with revulsion, knowing immediately they were not fit for anything but killing, which was generally true of all other races except the Thongal, K’Famir, and Frossians, who were considered merely dirty and occasionally useful.

On the planet where the stowaways had left the ship, however, the people did go on living. They all knew that something was wrong, but they didn’t know what it was. Something was missing, something they’d had before and didn’t have anymore. Still, the growths were good to eat, with juicy roots, fruits, nuts, succulent leaves. The women had babies that grew very fast, for there was no hunger on this world. No hunger, no danger, no threats. A good place, this world, even though it had no moon at all. Very soon the word for moon was forgotten.

“Wake up little one,” said Ahn’s woman to the new baby. “Wake up, take milk, grow up fast.” The older children played follow the leader, yelling to one another. “Up the tree, over the stump, down the bank, into the water, back again,” they cried. “Right, left, right, left, right, left!”

“The fruit is ripe,” the women called. “We should all pick it now, it’s so juicy and good. We can dry what’s left over.” Lots of women were having babies.

Seasons were long in this new world, but eventually the winter came, not a cruel winter, just chilly and unpleasant. The people took mud from the riverbank and piled it into walls. They learned to make thick walls, let them dry, then tunnel through them to get from one room to another. When the rooms were nice and dry, they could build new rooms on top. They made baskets from tree roots and limber branches. “We’re going out to get fruit,” they cried. “We’ll bring a basketful.”

They cleared everything from around the mud houses, making a smooth, packed-down place where the women could sit making baskets and the children could play. If the children were too noisy, the men would cry, “Cross the ground! Go into the woods!” The woods were safe; there were no beasts. The words for beasts were forgotten.

Rooms piled on rooms until their dwelling was as high as they could build it. “We have to make room for more,” they said. Some of them went a day’s journey away and started another tower to house some of the children the women were having. Soon each tower had daughter towers out in the woods, many cleaned places for the women to work and the children to play. They had to go farther now to get fruit and roots, but it was still a very good place.

Time went by. Daughter towers had granddaughter towers and great-granddaughter towers. The people fought over picking grounds. “This is my picking ground, our people’s ground! We’ve always picked here,” the men cried, waving clubs. “Go away.”

They went away. They had more and more babies. “We need a new place. We have to make room for more,” they said. They followed rivers, they went along shores, all over the world. They had babies, and the babies had babies. The food was far less abundant. Each generation the babies were smaller.

Time went by. A plague spread among the people. Most of them died. The forest recovered. The plague stopped, the survivors went on living. Another plague; again the forest recovered. An asteroid struck. The people lived on.

“Wake up,” the mothers said. “Wake up, drink.”

“Follow,” the children cried. “Right, left, right, left.”

“Fruit now,” the women said. “Now, hurry.”

“Commin,” cried the children. “We commin.”

“My pick ground,” the men said, clubbing one another.

Millennia went by. One night, when all the people were asleep, a Gentheran ship landed on a rocky outcropping where there were no towers. Gentherans in their silver suits came out of it and moved around looking at the towers and the cleared ground. They set tiny mobile recorders tunneling into the towers and tiny fliers hovering over the remaining forest. They talked among themselves and to the large ship in orbit.

“It looks like a total extinction coming!” said a Gentheran. “Can we get genetic samples?”

“Not without the permission of the people if they’re intelligent.”

“It’s hard to tell whether they are or not.”

“Leave it for now. We can always come back. You want to leave the monitor ship in place for a while?”

“We’ve never encountered an extinction in process before. It’s certainly worth recording.”

Accordingly, the large ship burned a deep, round hole in the rocky area, the monitor ship lowered itself into the hole and buried itself, with only a few well-camouflaged antennae and optical lenses exposed. A shuttle picked up the explorers.

On the planet, the people were so hungry they were eating the fungus that grew on the latrine grounds, down at the bottom of the towers. It was tasteless, but it kept them alive. When they couldn’t find food, they would bring dead leaves or bark or bodies to put in the latrine grounds for the fungus to grow on.

Most of the women were no longer fat enough to have babies, so they picked special women to fatten and have babies for everyone. The fungus they were eating was full of their own hormones and enzymes; they became smaller and smaller yet. They no longer had teeth. They no longer had hair. Their ears were longer, their eyes smaller.

“Wakwak,” woke the sleeping ones. “Rai lef rai lef rai lef,” moved the food gatherers. “Krossagroun, krossagroun,” they chanted as they went off into the remnants of the forest. “Mepik, mepik,” as they searched for anything organic. They had no names. Each one was “me.” At night all the “mes” lay curled against the tunnel walls, in the warm,

in the safe. Gradually, words lost all meaning. They made sounds, as crickets do.