The Miseducation of Cameron Post (30 page)

Read The Miseducation of Cameron Post Online

Authors: Emily M. Danforth

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Homosexuality, #Dating & Sex, #Religious, #Christian, #General

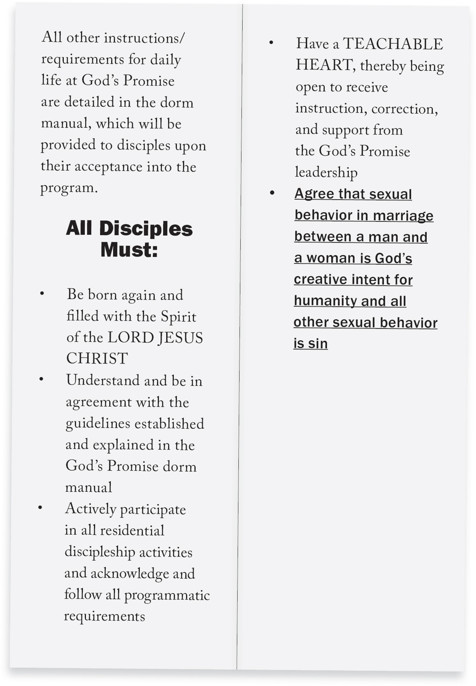

Before he left, Pastor Crawford said a long prayer in which he asked for God’s help in my recovery; then he hugged us all, even me. I let him, and afterward he handed me a manila envelope of application forms and rules for admittance that he’d had Reverend Rick fax over. The fee, by the way, was $9,650 per year, to be paid for with money left from Mom and Dad’s estate, an education fund they’d set up for me. Simple enough.

Part Three

God’s Promise

1992–1993

I

t was Jane Fonda who gave Ruth and me our official welcome tour of the God’s Promise Christian School & Center for Healing. We were in the Fetus Mobile for six hours straight before getting there. Six hours straight except for when Ruth pulled into the Git ’n’ Split in Big Timber to get gas and

treats

and to let me pee. Ruth didn’t even go. She could hold it like a camel.

Back then Big Timber still had the only water park in Montana, and it sat right alongside the interstate. When we passed, I craned to see the strange toothpaste-green looping slides as they towered out of a field housing cement vats of too-blue water. The place was packed.

It was the last good week of August, and even whizzing by like that, I could feel the urgency in the actions of the kids as they swarmed about the place. Everything was heightened the way it always is when summer is slipping away to fall, and you’re younger than eighteen, and all you can do is suck your cherry Icee and let the chlorine sting your nose, all the way up into the pockets behind your eyes, and snap your towel at the pretty girl with the sunburn, and hope to do it all again come June. I turned around in my seat and kept staring until I could just barely make out those green twisting slides. They seemed like tunnels from a science fiction version of the future, with the charcoal and purple Crazy Mountains all stretched out behind them like they didn’t fit at all, like painted scenery at the school play.

At the Git ’n’ Split Ruth bought string cheese and little cartons of chocolate milk and a tube of Pringles. She offered them up in the Fetus Mobile as though she was bearing frankincense and myrrh.

“I hate sour cream and onion Pringles,” I told the dashboard, where I had my feet planted until Ruth pushed them down.

“But you love Pringles.” Ruth actually rattled the canister.

“I hate sour cream and onion anything. All lesbians do.” I blew heaps of bubbles into my milk with the tiny straw that came cellophaned to the carton.

“I want you to stop using that word.” Ruth jammed the lid back onto the can.

“Which word?

Sour

or

cream

?” I plastic laughed with my reflection in the passenger-side window.

I had spent the week postintervention moving from numbness to outright, unabashed hostility toward Ruth, while she, on the other hand, became increasingly talkative and positive about my

situation

. She busied herself with the many

arrangements

to be made on my behalf: buying me dorm supplies, talking to Hazel about my early retirement from Scanlan, filling out paperwork, scheduling my mandatory physical, helping Ray haul the phone and TV and VCR from my room. That arrangement came first, actually. But the biggest arrangement of all: She canceled the wedding. She postponed it, that is.

“Don’t,” I said. She hadn’t even told me she was doing it, actually. I surprised her in the kitchen, overheard her on the phone with the florist.

“It’s not the right time now,” Ruth had said. “The priority is getting you better.”

“I mean it: Don’t. Don’t stop the show for me; I’ll live with not being there.”

“It’s not about you, Cameron. It’s about me, and I don’t want to have it while you’re away.” She had left the room after that. But she was lying, of course. It was completely

about me

. Completely.

I had to be babysat at all times. Someone in my condition couldn’t very well be left alone. I met with Pastor Crawford each day, an hour or two at a go, but I never said much of anything. They were just Nancy Huntley sessions with God thrown in. I ate breakfast with Ruth, lunch with Ruth, dinner with Ruth and Ray. I stared out my window a lot. One afternoon I thought I saw Ty circling our block in his truck, around and around. I’m sure I did. But he never pulled up to the curb, put it in park; never charged up the stairs to teach me the violent version of the very same lesson God’s Promise would be attempting to teach me soon.

During my lockdown Ruth was Ruth: chipper—forced, but chipper. Ray was Ray: quiet and even more unsure of what to say to me. And Grandma was nowhere. That whole week she ghosted around the house, wouldn’t find herself alone in a room with me, took off in the Bel Air to who knows where for hours at a time. We ended up in the kitchen together one afternoon. I think she was hoping that I was still out meeting with Crawford, but I surprised her as she was mixing up a can of tuna with mayonnaise.

I didn’t try to be proud. I thought maybe I had just one chance. “I don’t want to go, Grandma,” I said.

“Don’t look at me, girl,” she said, still mixing the mayo in thick. “You brought this on yourself. This is all your doing, every last bit of it. I don’t know as Ruth’s way is right, but I know you need some straightening out.”

I don’t think she realized that her word choice was sort of funny, and it wasn’t really, right then, anyway.

“You’ll be fine,” she said, putting the mayo back into the door of the fridge, taking out the jar of sweet relish she wasn’t supposed to eat. “You do what they say. Read your Bible. You’ll be just fine.”

It seemed like she was saying it as much for her as for me, but that’s where the conversation stopped. I only saw her once more before we left. She emerged from the basement as we were loading the FM, gave me a loose hug that grew a little tighter right before she let go.

“I’ll write you some, once it’s allowed. You write too,” she said.

“Not for three months,” I said.

“You’ll be okay. It will fly by.”

Lindsey called once, she just happened to, probably wanted to know what I thought of the care package, but Ruth answered the phone, told her that I’d be

going away to school this year

and

wouldn’t be able to continue to communicate with her any longer

. Just like that. I’m pretty sure she tried calling back, but I wasn’t allowed to answer the phone. Jamie stopped by and Ruth at least let him come into the entryway, but she hovered in the other room, made it obvious that she was listening.

“Everybody knows now, huh?” I asked him. It didn’t seem like there was any point wasting words by talking around the only thing worth talking about right then.

“They know one version,” Jamie said. “Brett’s been telling people. I don’t think Coley has.”

“Well, it’s the only version they’d believe, anyway,” I said.

“Probably.”

He hugged me fast, told me he’d see me at Christmas if the warden allowed it. That made me laugh.

I could have snuck out. I could have made secret phone calls. I could have rallied forces on my behalf. I could have. I could have. I didn’t. I didn’t even try.

By an hour outside of Miles City, Ruth had already given up on lecturing me on appreciating

God’s gift of a facility like this right in my own state

. I think she had given up on instilling in me a positive attitude before we even got on the road, but she quoted some scripture and walked through her lines as though she had written her little speech out beforehand. And knowing Ruth, she probably had—maybe in her daily prayer journal, maybe on the back of a grocery list. Ruth’s words were so stale by that point that I didn’t even hear most of them. I looked out my window with my nose tucked into my shoulder and smelled Coley. I was wearing one of her sweatshirts even though it was too hot for it. Ruth thought it was mine or she would have piled it into the cardboard box with the other things of Coley’s, of ours, that she and Crawford had confiscated, many of those things items from our friendship and not necessarily from whatever it was that we’d become those last few weeks: snapshots, lots of them prom-night pictures; notes written on lined paper and folded to the size of fifty-cent pieces; the thick wad of rubber-banded movie tickets, of course those; and also a couple of pressed thistles, once huge and thorny and boldly purple, now dried and feathery and the ghost of their original color, dust in your hand if you squeezed too hard, and Ruth did. The thistles I’d picked at Coley’s ranch, hauled back into town, and tacked upside down to the wall above my desk. But the sweatshirt, buried at the bottom of my laundry basket beneath clean but not-yet-folded beach towels and tank tops, had escaped. It still smelled like the kegger campfire at which she’d last worn it and something else I couldn’t place, but something unmistakably Coley.