The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (18 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

Claims of Specific Hellenistic Finds

Ultimately, an accurate history of Nazareth can be determined only on the basis of datable material excavated on site. Is there, then, specific material in the Nazareth basin that substantiates human presence there in the pre-Christian centuries?

To answer this question, we shall begin with an examination of the two most referenced “Hellenistic” claims in the literature. They involve a group of six oil lamps on the one hand, and part of a single oil lamp on the other. These claims lie at the heart of pre-Christian Nazareth. The amazing and almost inexplicable sagas that accompany these finds are an eye-opener to the researcher, and reveal that the very heart of Nazareth archaeology is terribly flawed.

The Richmond report

In 1930, while laying the foundations for a private house in Nazareth, a tomb was discovered approximately 320 m southwest of the Church of the Annunciation.

[205]

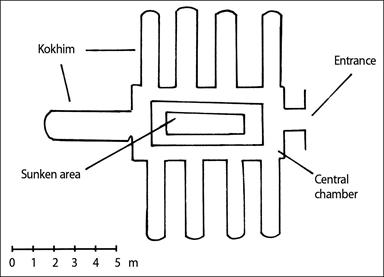

As is customary in the Holy Land, work was immediately suspended and the Department of Antiquities was notified. An inspector came to the site, and subsequent excavation uncovered a rectangular underground chamber with nine shafts (

kokhim

) radiating outwards from three sides. The tomb is Bagatti’s number 72 (

Illus.2

).

[206]

It contained human bones and some artefacts, including six oil lamps, a juglet, beads, and small glass vessels. These finds were summarized in a brief report published in the 1931 issue of a new journal,

The Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine

.

[207]

The report, entitled “A Rock-cut Tomb at Nazareth,” consists of a mere half-page of prose, followed by three pages of diagrams and photographs. It is signed “E.T.R.”

Born in 1874, Ernest Tatham Richmond joined the Royal Asiatic Society in 1910 and served as a functionary of the Ministry of Public Works in Cairo when Egypt was a British Protectorate (1914–22). He authored a number of articles on Egypt. and was subsequently appointed Director of Antiquities in Palestine. His signed 1931 report on this Nazareth tomb may have been authored by Richmond himself after a personal visit to the site, or it may be based on information received from his inspector, Naim Effendi Makhouli.

The report itself is unremarkable except for one word in the final sentence:

Tomb No. 10

. Two glass vessels (Pl XXXIII.5, third and fourth from left), six Hellenistic lamps (Pl. XXXIV.2), and iron, glass, and pottery fragments.

E.T.R.

This is the first mention in the Nazareth literature of specific Hellenistic evidence. If Richmond were correct, and if six Hellenistic oil lamps were indeed found only a few hundred meters from the venerated area, then the case for Nazareth existing in the time of Jesus would be virtually assured. Such is the awesome importance of the single word “Hellenistic” in this brief and obscure report.

However, a glance at the photo (

Illus. 3.1

) shows to even an amateur that none of the lamps signaled by Richmond is Hellenistic. The two in the upper row have been specifically dated by Israeli specialists to between “the second half of the first century A.D.” and the third century,

[208]

that is, Middle-Late Roman times. Two of the lamps (lower left and lower right) are of the bow-spouted type, which will be studied in Chapter Four. They are dated in Galilee from

c

. 25 CE to

c

. 135 CE.

[209]

The remaining two lamps are Late Roman (see below). In other words, all six oil lamps date to the common era.

A more precise dating for several of the lamps in the Richmond report can be ascertained from an invaluable 1978 publication,

Ancient Lamps in the Schloessinger Collection

. It itemizes over five hundred Hellenistic and Roman oil lamps from Syria, Palestine, and Arabia. Authored by Renate Rosenthal and Renee Sivan, this compendious work contains a description and photo of each lamp, together with a note on provenance, condition, dating, type, ornamentation, and a comparison with similar specimens found elsewhere. Rosenthal and Sivan are aware of Mr. Richmond’s report and specifically date two of his six lamps (upper left and upper right) to between 50/70 CE and 200 CE.

[210]

They date the lamp at the lower right to

c

. 100 CE,

[211]

which corresponds to the Middle Roman period. The remaining three lamps consist of an undecorated bow-spouted lamp (lower left) dating to the latter half of I CE, and in the lower middle, two rather unusual lamps with stubby nozzles. Parallels to these latter have been variously dated III–VI CE.

[212]

Since we are using 70 CE as the beginning of Middle Roman times, all six oil lamps in

Illus. 3.1

are Middle Roman, Late Roman, or Early Byzantine.

Illus. 3.1

. Six oil lamps of the Roman period found in

Tomb 72.

(Photo from QDAP 1931, Pl. XXXIV.2)

One can only speculate how the word “Hellenistic” entered Richmond’s report. The discrepancy in dating is huge, amounting to between three and five centuries. No expert would be capable of such a mistake.

[213]

Nor would he treat these six lamps as a group, for they represent strikingly different types. It is remarkable that this egregious error survived the scrutiny of the Department of Antiquities of Palestine, in whose

Quarterly

the report was published. But then, Richmond was himself Director of the Department.

These six Richmond oil lamps underwent a second stage of misrepresentation a few years after the publication of Richmond’s report. Fr. Clemens Kopp, whom we have previously met,

[214]

penned his first installment of “

Beiträge zur Geschichte Nazareths

” in 1938. He commented on Richmond’s “Hellenistic” assessment as follows:

R[ichmond] classifies 6 lamps by date very generally as “Hellenistic,” according to the accompanying photographs of the finds they must surely go back at least to 200 BCE.

[215]

This statement goes considerably beyond Richmond’s error of the single word “Hellenistic,” which denotes a period continuing into the first century BCE. Fr. Kopp supplies a much earlier date: “at least… 200 BCE,”

i.e

., the third century BCE. This magnifies the previous mistake, and we can only wonder what made the German choose a date that has not the remotest relevance to the lamps in question. Even an amateur collector would not be so misled, much less an antiquities dealer, not to mention a writer on archaeological matters such as Fr. Kopp. To date this group of Roman-Byzantine oil lamps before 200 BCE is a monstrosity—it errs in some cases by over five hundred years. There is no question of an inadvertent slip, for the priest claims to have examined the accompanying photographs himself and appeals to his own expertise. The only possible conclusion, then, is that deception is heaped upon deception.

The priest’s

modus operandi

is transparent. Kopp fabricates Hellenistic evidence in an attempt to bolster the case that Nazareth existed before the time of Christ. At the same time, he undergirds the Church’s position by providing a false Hellenistic claim, one readily available for subsequent citation in the Nazareth literature.

In his 1963 book,

The

Holy Places of the Gospels

,

[216]

Kopp continues the same line as in his work of a generation earlier: “Two kokim sites, untouched by plunderers, have been discovered in Nazareth recently. The contents show that one belongs to the period about 200 B.C., the other to the first century A.D.” The first of these sites must refer to the Richmond tomb, for nowhere else does Kopp claim II BCE evidence. A few years later Bagatti corrected this misdating.

[217]

As for the “first century A.D.” site (Tomb 70), Kopp is probably correct—some oil lamps from that tomb may date to the latter part of I CE, as we shall see in Chapter Four.

It is self-explanatory that if the village of Nazareth existed in the time of Jesus, then it came into existence sometime before the turn of the era. For the tradition, then, Nazareth must have been either born or already in existence in Hellenistic times. Thus, one epoch depends on the other: the existence of a viable village at the turn of the era (one with a synagogue and crowd that could accompany Jesus, Lk 4:16–30) depends on its existence already in Hellenistic times.

This appears to be the inspiration behind Kopp’s dissimulation of evidence. The shocking lack of finds of a Greco-Roman settlement in the basin, already noted by Tonneau in 1931,

[218]

placed an enormous burden on the tradition to materially demonstrate that Nazareth existed in the Hellenistic era.

The kokh tomb

In his 1938 Nazareth report, Kopp also considers the tomb in which the Richmond artefacts were found. Technically, this is known as a kokh tomb. We shall briefly consider this type of Jewish burial before returning to what Kopp has to say about the Richmond tomb.

Kokh

literally means “grave, cave for burial” in Mishnaic Hebrew. The plural is

kokhim.

[219]

Probably imported from Egypt and first noted in Palestine about 200 BCE,

[220]

the kokh tomb “virtually became the canonical form of the Jewish family grave” from about 150 BCE to 150 CE.

[221]

This form of burial continued in use well into Byzantine times.

[222]

The exact layout of the tomb, the dimensions of each kokh, and the number and placement of kokhim are specified in the Mishna.

[223]

The typical kokh tomb had a central square chamber, often with a pit dug into the floor that allowed a man to stand upright. From each side (all except the entrance) one to three kokhim were hewn horizontally into the rock, radiating outwards from the central chamber.

[224]

Each kokh was about one meter high and two meters long, and was designed to accommodate a single body.

[225]

Illus

. 3.2 shows the plan of the Richmond tomb (Bagatti’s no. 72), a typical kokh tomb. Over twenty tombs of this type have been found in the basin, and a number have probably not been discovered.

[226]

Most were robbed in antiquity, but three kokhim tombs at Nazareth fortunately contained movable finds at the time of discovery.

[227]

Mostly pottery, such finds include jars, oil lamps, glass, and metal objects dating to Middle Roman and later times. These critical artefacts—most especially the oil lamps—allow us to date the birth of Nazareth.