The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (9 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

It is evident that the Iron Age settlement was of considerable size, even though we only know one tomb (T. 75) from this era. Yet that multi-chambered tomb served many people, and certainly more tombs were in the basin. Eighty-three datable Iron Age artefacts have been found and are itemized in

Appendix 2.

This is a considerable number, and it is likely that a good deal more material, together with structures, lies buried in the basin under the present houses of Nazareth. From the extant evidence we can conclude that the western slope of the basin, including the Franciscan property, was used as a necropolis through both the Bronze and Iron Ages. In the latter period the venerated sites were also used for agricultural purposes, witnessed by Silos 22 and 57.

Due to the sloping and rocky nature of the terrain it is unlikely that there were Iron Age dwellings in the area of the Franciscan property and that evidence of them has long since disappeared. More likely, however, is that the inhabitants lived on the valley floor and used the slope for funerary and agricultural use.

[105]

Combining historical data, the evidence from the ground, together with that from surveys of Southern Galilee, it is probable that a new group of people entered the Nazareth basin about 1100 BCE, and that they continued to live there for about four centuries. Habitation in the basin ended within a generation or two of the Assyrian conquest. This model of Nazareth chronology is consistent with the evidentiary profile, and with the assessment of Gal and Aviam, noted above, that Lower Galilee was almost totally deserted during the seventh century BCE.

Excursus: The Bronze Age location of Japhia

It was noted above that the most ready access to the Nazareth basin is from the southwest, where the village of Japhia (Yafa, Yaphia) was located in the time of Jesus. This site has been variously measured from one to two miles from Nazareth (1.6 to 3.3 km), depending on the point in Nazareth from which one measures. Modern Nazareth is so much larger than in antiquity that it is now contiguous with the village of Japhia.

The first-century historian and general Josephus wrote that Japhia was the “largest village in Galilee.” He strengthened its walls in 66 CE and himself resided there for a time. When the Roman general Trajan besieged the town during the first Jewish War (in the summer of 67), Japhia had a double wall and put up stiff resistance. According to Josephus (admittedly known to exaggerate) 15,000 inhabitants were slain and 2,130 sold as slaves.

[106]

Roman Japhia has been located with certainty, and the principal excavations there have uncovered a synagogue of III–IV CE.

[107]

There was also, however, a much older town known in Jewish scripture as ‘Iaphia’ (ypy Josh 19:12). This is apparently the ‘Iapu’ mentioned in the Egyptian Amarna letters (XIV BCE). If this literary association is correct, then the settlement had some international significance in the Late Bronze Age, which in turn indicates that it was a town of significant size.

The location of the Biblical town of Iaphia/Yapu is unknown. It was certainly not at the site of Roman Japhia, for no Bronze-Iron age structures or artefacts have been found in the excavations there. Towns sometimes drifted, however, moving one or even more kilometers over time. This typically occurred in three cases: (a) the center of population gradually moved over a period of generations or centuries; (b) after a sudden dislocation (as after destruction by man or earthquake) the town was rebuilt nearby; or (c) after a dislocation or destruction the settlement was left vacant for a period of time, and only later (perhaps centuries later) rebuilt in the general vicinity.

Some settlements are known to have moved over time. For example, modern Jericho is at some remove from the site of Kenyon’s excavations, and present-day Cana in Galilee is almost a mile from the site of the putative ancient town. Settlements often enough changed position from century to century, as inhabitants came and left, as orchards were planted, as the environment changed, and for other reasons.

At least one scholar has argued that the Bronze-Iron Age town of Japhia was 6 km northeast of Nazareth, at the site now known as Mashhad (Mishad, el-Mecheh—see

Illus. 1.2

).

[108]

According to this theory, Japhia moved to the Roman location (3 km SW of Nazareth) over the course of a millennium. This is improbable, however, not only because of the great distance involved (9 km), but also because Mashhad and Roman Japhia are on different sides of the Nazareth divide, the East-West crest of hills that is quite pronounced in this area.

From the results of this chapter, a new possibility can now be considered. Closer to Roman Japhia, in fact only three kilometers away and on the same side of the ridge, are the Bronze-Iron Age remains of the settlement we have been calling “Nazareth.” Though only a small area of the basin has been excavated, it is enough to show that a substantial settlement was there in Bronze-Iron Age times. Five Bronze Age tombs (not an insignificant number) yielding approximately a hundred itemized artefacts have come to light. The four tombs close to one another on the Franciscan property constituted a Bronze Age necropolis, and must have served a town of considerable size. Approximately three-quarters of a kilometer away is Tomb 81 (

Illus. 1.3

). This dispersion suggests that at least during the MB IIA (when Tomb 81 was in use) the settlement was of substantial size.

Such dispersion is equally evident in the Iron Age. Two extant tombs from that period (the Vitto tomb and Tomb 75) are separated by 700 m.

[109]

Tomb 75 had an elaborate plan and was a type that served many people. Thus, both the type of structural finds and their locations suggest a sizable settlement in the Bronze and Iron Ages, not merely a hamlet of a few people. That settlement might well have been biblical Japhia. The town was important enough to be mentioned in the Bible and Amarna letters, and sufficiently populous to supply a corvee of labor to the Pharaoh. If our suggestion is correct, then much Bronze and Iron Age evidence of ancient Japhia, probably including more tombs, once existed in the Nazareth basin. Due to the presence of modern buildings much of the basin has, in fact, never been excavated. Unfortunately, again due to those same buildings, much of the ancient evidence has probably been permanently destroyed.

Thus, it is possible that the Bronze and Iron Age evidence discussed in Bagatti’s

Excavations

and in other scholarly literature in fact describes biblical Japhia. This possibility is magnified when we consider (in Chapters Two and Three) that there was no habitation in the Nazareth basin between the Iron Age and Middle Roman times. After the dislocations brought on by the Assyrian invasions in the late eighth century, the settlement of Japhia may have moved three kilometers to the southwest, from the higher valley (the Nazareth basin) to the lower. By late antiquity, Japhia was located where its known Roman ruins have been excavated. Those ruins mark the town that the Jewish general Josephus fortified and defended in I CE.

Chapter Two

The Myth of

Continuous

Habitation

The

Great Hiatus: Part I

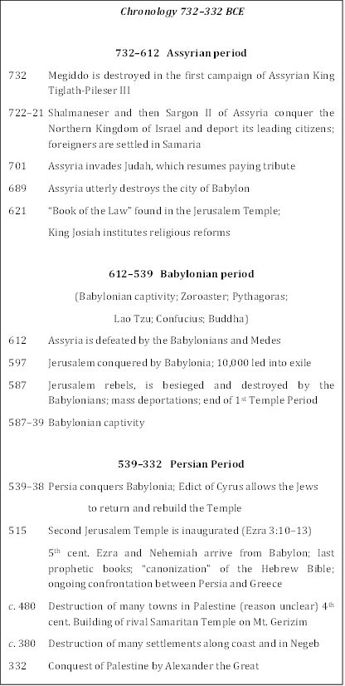

(732–332 BCE)

|

The Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian Periods

The end of habitation in the Nazareth basin

The armies of Tiglath-Pileser III swept through the Galilee about the year 732, and many inhabitants of the Northern Kingdom were taken into exile and replaced with people from other conquered lands (2 Kg 15:29). Some years later Shalmaneser V invaded Samaria, and finally Sargon II completed the Assyrian conquest of the Northern Kingdom. By his own records he deported 27,290 inhabitants (2 Kg 16:6). Initially, Aramaeans from the conquered town of Hamath were settled in their place, then inhabitants from defeated Cutha and from Babylon. The contemporary prophet Isaiah lamented: “He has humbled the land of Zebulon and the land of Naphtali,” and the region earned the epithet “Galilee of the Gentiles” (Isa 9:1). We recall the words of Zvi Gal quoted at the end of Chapter One: “It seems that the entire Galilee was abandoned after the Assyrian campaign of Tiglath-Pileser III in 733–732 BCE,”

[110]

and “Lower Galilee was practically deserted by the end of the eighth century.”

[111]

M. Chancey offers the following particulars regarding the general destruction in Galilee associated with the Assyrian conquests:

Excavations have corroborated the surface surveys. Tel Mador yields evidence of occupation from the tenth and ninth centuries BCE and from the Persian period but only one sherd from the eighth century BCE. Excavations at Tel Qarnei Hittin have demonstrated that a sizable city was destroyed in the late eighth century BCE, with no subsequent occupation. The settlement at Hurbat Rosh Zayit, probably a Phoenician community, was likewise destroyed in the mid-eighth century BCE, with no resettlement afterwards. Excavations at Hurrat H. Malta, Tel Gath-Hepher, Hazor, Kinneret and Tel Harashim have revealed dramatic decreases in population after the eighth century BCE. The implication is that not only did the indigenous population leave Galilee, but the Assyrians did not repopulate it.

[112]

The physical record in the Nazareth basin also comes to an end in the Late Iron Age (800–587

BCE

).

[113]

Unfortunately, the published archaeological record alone does not permit a more precise dating. We can affirm, in any case, that no evidence at Nazareth has been dated

with certainty

to the years following the Assyrian conquest of 732.

[114]

The ten artefacts that have been clearly dated to Iron III may well come from the generations before the Assyrian conquest.

[115]

The archaeological record of the region, as seen in the above citation and in the conclusions of Zvi Gal, makes it unlikely that the settlement continued into the seventh century. Thus, 732

BCE

is a

terminus a quo

for the beginning of a long hiatus in the Nazareth basin. I call it the Great Hiatus (or simply the hiatus), a multi-century gap in evidence of human habitation.

The Babylonian and Persian periods are entirely unattested by evidence in the Nazareth basin. Even the Church itself nowhere claims finds from the sixth, fifth, and fourth centuries. We shall see that this is odd in view of the fact that the Church maintains the doctrine of continuous habitation, that is, that there has been continuous human habitation in the basin since the Iron Age (see below). Despite this overarching claim, the years 600–300

BCE

are “empty centuries,” quite ignored in the literature. For example, in his 325-page

Excavations in Nazareth

, Bagatti jumps directly from the Iron to the Hellenistic Period (p. 272), simply skipping the intervening centuries without further ado. He is not the only one to do so. In vain do we scour the literature for any mention of Babylonian and Persian evidence at all. Not a single artefact, much less construction (tomb or wall foundation) dates to those eras. At Nazareth, the years 612–332

BCE

are entirely mute.

I have suggested the identification of the Bronze-Iron settlement of “Nazareth” with biblical Japhia.

[116]

The historical and archaeological data reinforce this identification, for it is altogether probable that Japhia—being a significant town in northern Palestine—was destroyed by the Assyrians, along with Megiddo, in Tiglath-Pileser’s campaign of 732 BCE. Perhaps the town survived another decade before meeting destruction in the second wave of conquest under Shalmaneser and Sargon. When eventually rebuilt, Japhia was no longer located in the Nazareth basin but three kilometers to the southwest. We cannot be certain when that rebuilding took place, for to my knowledge no excavations at Japhia have established this fact. This is not surprising, for little evidence from the Galilee survives from the seventh–sixth centuries: