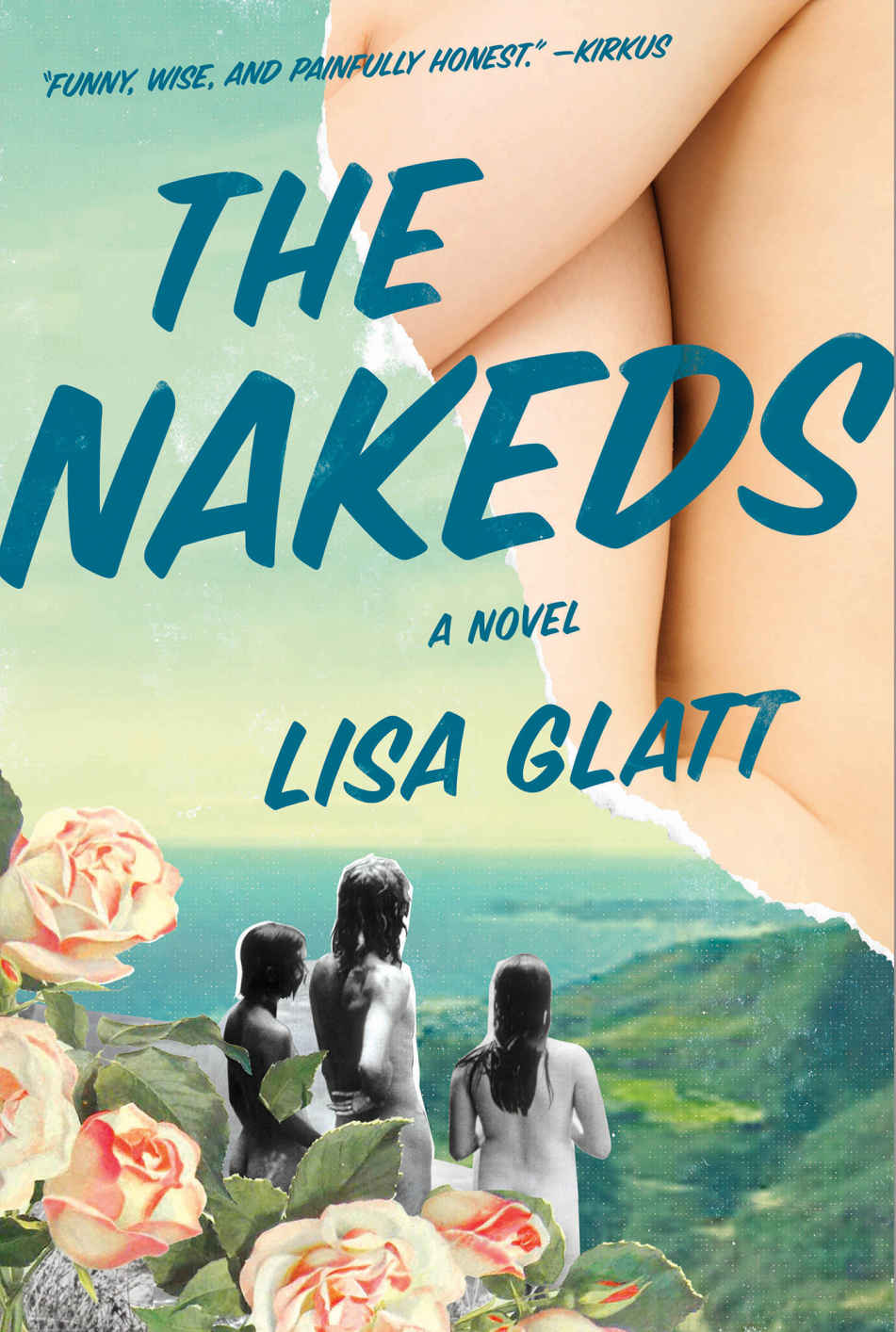

The Nakeds

For my love, David

•

For my mother, Iris Stanton, who’s gone,

but whose life and adventures continue to make their way onto my pages

What spirit is so empty and blind that it cannot recognize the fact that the foot is more noble than the shoe, and skin more beautiful than the garment with which it is clothed?

—Michelangelo

1

HANNAH LIVED

in a Southern California beach city without sidewalks, with lawns and flower beds that went right down to the curbs, and today, because it was Monday, trash day, those curbs were lined with fat green bags and reeking metal bins. And today, because her parents were fighting, Hannah snuck out the front door and attempted to walk to school alone.

She’d stood in the dining room, listening to them scream

fuck this

and

fuck that

and

fuck you

and

oh no, mister, fuck you

. She hid behind a tall chair and watched them from between the wood slats. Her father stood in the corner, shirtless in gray sweatpants and socks, his hairy chest puffing up. “This is no life,” he said. “Look at the three of us trapped here.”

“Trapped?” her mother said in a low whisper. “Who’s trapped?” She was only half dressed for work, cotton pajama bottoms and silk floral blouse, a gold hoop earring in one ear and nothing in the other. Her hair was sprayed stiff like a helmet and she had two perfectly rigid, solid curls twirling past each ear and down each cheek that bounced as she hollered. “Do you think I’ll let that shiksa make a fool of me?”

“Enough, Nina,” her father kept saying. “You’re going to make this worse.”

“Me?” she screamed. “Who’s the dog here? Tell me that,” she demanded. “Who behaves like an animal?”

Her father looked around the kitchen and shook his head. “How did we get here?”

Here

was an A-frame cottage, a small three-bedroom house that her dad had always claimed to love.

Here

was a home the two of them had picked out together with Hannah’s childhood in mind.

Here

was the weather the two of them bragged about to their friends and family on the East Coast—so many sunny days in a row, even in the winter months.

Before she’d left for school, Hannah had surveyed the breakfast table where two full cups of coffee sat cooling, where spoons and forks and knives for three splayed out in a messy, optimistic bundle. A loaf of challah, twisted and sprinkled with sesame seeds. Paper napkins. A glass bottle of milk. A cardboard cylinder of oatmeal. An apple sliced in quarters.

She took one last look at them. Her mother held a tall glass above her head and aimed it at her father’s face.

“It’s not worth working on. You’ll see,” he said.

Hannah had seen enough.

She snatched her lunch from the dining room table—a brown bag, with her name on it in her mother’s messy cursive, that now bounced against her thigh—and headed toward the foyer and out the front door.

It was spring 1970. Her mother had told her last night while tucking her in that it was a whole new era. She talked about NASA’s Explorer 1, an unmanned satellite, reentering Earth’s atmosphere just a week earlier, after twelve years in orbit. “And soon, within days, men are going to soar into space. Imagine that, Hannah,” her mom said. “Anything is possible.” When Hannah grew up she could be a doctor or even an astronaut. “You could go to the moon one day.”

Hannah shook her head.

Her mom laughed. “I’m not much of a traveler either.”

Now, walking down the driveway, Hannah thought about that unmanned satellite, spinning around in space for a dozen years, launching before she was even born. She waved at the next-door neighbor, Mr. Perkins, who was coming down his porch steps, carrying a briefcase. His black hair was wet.

“You like my new car?” he asked her. “It’s a Gremlin,” he said proudly. “Tell your dad to come by after work to take a look.” He opened the door, tossed his briefcase into the backseat, and sat down behind the wheel.

After an awkward, wordless back-and-forth about who should go first, Mr. Perkins accepted her offer, pulling out and waving good-bye to Hannah behind the closed window.

She wished they lived on a street with sidewalks and that the neighbors’ lawns weren’t so neat and manicured. She walked on those lawns, tentatively, using stepping stones where she could find them. She waited a few minutes until the O’Briens’ sprinklers sputtered to an end, and then moved through their yard. Halfway down the second block, an old woman in a nightgown and fluffy slippers stood on her porch, shaking her head. Hands on her doughy hips, she screamed at Hannah to get the hell off her lawn. “Can you hear me? I’m talking to you, little girl!”

Across the street, a German shepherd, chained behind a wire fence, barked and growled and bared his teeth.

“Are you deaf? Something wrong with you?” the woman said. “Can’t you hear me? Are you deaf?” she repeated.

Hannah was many things, but deaf was not one of them.

She was shy.

She was bookish, in first grade but reading at a seventh-grade level.

She was nervous, prone to seriousness and hypochondriacal thoughts already.

She was worried about the new era her mom had mentioned.

She was quick to tears.

She was fearful, especially afraid of strangers and thunder, fog and the school nurse.

She was short, the second shortest in her class, only taller than Eddie Epstein, who had confided in her that he was taking special vitamins that were supposed to help him grow. Eddie was a nice boy, a boy who smiled when he talked to her and asked about her weekend, but still she was very afraid that those vitamins might work. When he’d returned from the nurse’s office and sat down in the adjacent desk, Hannah stared at him—his little shoes and jeans, his plaid shirt and delicate shoulders, the tiny denim jacket hanging over the back of his chair—and she imagined Eddie growing and growing, sprouting right out of his desk, taller and taller, passing huge and handsome Tommy Miller, passing pretty Janet Murray, passing Mr. Henderson and the top of the chalkboard too, until his head brushed the ceiling, until he left her behind.

She was timid. She didn’t shout out or complain when she should have. Like right now, that woman’s voice again. “Get off my goddamn lawn, little girl. You’re going to mess up everything.”

The air was sweet from the roses to the left of her and sour from the garbage on her right. She held back tears and imagined her destination, the school itself, all concrete and redbrick, looming at the end of the cul-de-sac she hadn’t yet reached. She imagined the hall monitor, a fifth-grade girl full of smarts and purpose with a whistle around her neck, standing at the front of the double glass doors. The last bell would be ringing in a matter of minutes, the intercom starting up, a crackling static, and then finally the principal’s voice would break through.

Hannah was almost there.

She was stepping off the curb.

She wanted to be someone else, a stronger, bolder girl—a girl who might have surprised the cranky woman on the porch with a

fuck off

or

no fucking way

—phrases she’d heard lately at home and during recess. She stepped into the street and heard those words in her head, trying to call them to her throat and mouth, but they wouldn’t come—her lips shut as if with paste.

And there in front of her, her two obedient feet, one black shoe stepping forward and the other one following.

“That’s right, there you go,” the woman said. She’d stopped shrieking, at least, but was now gloating. “Go on now.” A bad winner, puffed up and sure of herself, her hand rising from her belly to shoo Hannah away. The German shepherd snarled and ran toward the fence, but the chain yanked him back so that he was on two legs, dancing, fiercer than ever.

Hannah was aware of her heart and lungs, her own breaths—a white puff each time she exhaled. She was aware of the wind too, which had picked up—her face cold and damp with sweat.

When the woman’s front door slammed shut and she was finally gone, Hannah felt momentarily relieved. But there was a circular window on that door and the woman’s face appeared again from behind it. She’d pulled the curtain to one side, spying, making sure that Hannah didn’t change her mind and disobey, and she was mouthing something still.

Hannah didn’t disobey, even when she was past the woman’s house and the one next door and the one next door to that one.

She was careful, precise, curling around the trash cans—her body so close without actually touching them.

She heard the brakes.

She turned and caught a glimpse of the driver’s startled face behind the wheel, and understood the screech was coming for her.

And it was a collision, yes, but a convergence too, an unfortunate union: metal to skin, fender to plaid dress, and, finally, fat black tire to bare calf, to lacy sock and perfectly shiny shoe. It was a confrontation, the briefest coming-together and breaking-apart, which propelled Hannah into the sky so that she was as far away from her warring parents and the cranky woman as possible, in the air, turning over—her two feet not even sharing the earth with them.

AFTER ASHER

Teller hauled the three heavy, silver bins from the side yard out to the curb, he stood in the kitchen, looking out at the backyard and the dry grass he’d been neglecting lately, the pool he hadn’t cleaned in a week. Hannah’s pink bike stood in the corner, propped up against the fence, and he felt guilty just looking at it. He’d promised her a weekend, two afternoons of bike-riding lessons, and he’d promised her training wheels more than a month ago, and he hadn’t come through. Next to the hose he hadn’t uncoiled in weeks, the bike stood there, a two-wheeler with fringe hanging from the handlebars, with stickers and decals, with a bell and a wicker basket, all the unnecessary decorative accoutrements but no training wheels, and the weekends had come and gone, and he hadn’t taught her anything.

He drained his cranberry juice in one long pull and set the glass down on the kitchen counter. After he left Nina for good, he’d hire a gardener to come once a week to take care of things, he told himself. He’d get Hannah those training wheels and teach her to ride. He’d give her that weekend and every weekend that came after. He’d be a better dad once he was out of there. He’d be a better surfer. Hell, he’d be a better dentist, a better everything, once he got out. Without rinsing the glass, he left it in the sink, then went upstairs and pulled out the receipts.

He was a man with a plan, a man who wanted to be caught cheating on his wife, so he’d leave those receipts on top of the dresser, next to Nina’s jewelry box, wanting her to have proof before she even clasped her watch or put on her earrings. Usually the receipts hid in his wallet for months at a time and if he saw them again, they were faded, nearly illegible surprises he unfolded and held up to the light, squinting and trying to remember where he’d been with Christy Tucker, what they did and where they did it.

He knew that the circumstances of their meeting and six-year affair made him a cad, a cheat, a rotten man and father, but he was what he was and he’d done what he’d done, and worse, he had no intention of stopping or giving her up. What he wanted was to start a new, better life. He’d even been thinking lately about asking Jesus into his heart. Who better to forgive him?

He met Christy Tucker more than seven years ago. She was the young woman sitting behind the sliding window who handed Nina the clipboard and papers to fill out when they came in for his wife’s monthly checkups. Nina had been irritable since conception, it seemed to Asher, and when he thought about it now, more than a half dozen years later, she was irritable well before she became pregnant with Hannah. Nina had stopped liking him a year or two into their marriage, it seemed to him, and it was hard to like someone who didn’t like you, didn’t like the simplest things that came out of your mouth, comments about the weather or the coffee or the tie the newscaster was wearing. A man should be able to criticize the newscaster’s wardrobe without eliciting a hateful sneer from his wife.

Nina had made her ob-gyn appointments on Fridays and insisted that Asher make a new schedule for himself. He was head dentist. It was his practice. Driving her to and from the doctor’s office was the least he could do. So once a month he had accompanied Nina to her appointments. She’d wanted him only as far as the waiting room, though, and had insisted he stay on one of the plastic-covered couches when she went in to see the doctor. Asher noticed other husbands accompanying their pregnant wives inside and felt foolish and rejected waiting alone.

“I feel like a schmuck sitting there,” he told her in the car on the way home.

“I don’t know what to tell you, Asher. Maybe it’s me, maybe it’s hormones, or maybe it’s us.” She sighed and turned from him, looked out the passenger-side window until they reached their driveway.

Still, month after month, he accompanied his moody wife, her belly growing like his fascination with the pretty receptionist. Month after month, he kept up with Christy Tucker’s changes. She wore a new pale lipstick. A ponytail. A yellow T-shirt under her white jacket. She was sunburned. She was tan. Her pert, little nose was peeling, a patch of tender red skin exposed. She wore small hoop earrings and a gold cross around her neck.