The Nice and the Good (31 page)

Read The Nice and the Good Online

Authors: Iris Murdoch

McGrath was cracking walnuts with a pair of silver nut crackers. “Here, Sir, have half. They’re quite good inside.”

Ducane felt the dry wrinkled morsel pressed into his hand. He moved back. Whatever he did he must not share a walnut with McGrath. That meant something too, only he could not remember what.

“Show me what there is to see and then let’s get back.”

“Not much to see really, Sir,” said McGrath munching walnut. “This was where the candles went. I’ll lay the rest of the stuff out.”

McGrath placed the candles in a row along the back of another trestle table which stood up against the white wall. A narrow black mattress lay upon the table. “That was where the girl went, Sir,” said McGrath in a low reverential voice.

McGrath returned to the other darkened table and then began to lay out a number of articles upon the mattress. First there were a number of well-corked clearly labelled glass jars such as one might find in a kitchen. Ducane looked at the labels: poppy, hyssop, hellebore, hemp, sunflower, nightshade, henbane, belladonna. The black bread and a pile of walnuts were laid next to them. There followed a large packet of table salt, a small silver-gilt bell, a Bible, a battered Roman missal, some sticks of incense, an elongated piece of silver on a stand with a cross bar close to the foot of it, and a slim black whip. The bell tinkled slightly. McGrath’s pale red-haired hand closed over it.

McGrath placed the tall piece of silver in the centre of the table behind the mattress. Ducane thought: of course, a tau cross, a cross reversed.

“For the five senses, you see. Mr Radeechy explained it to me once. Salt for taste, flame for sight, bell for sound, incense for smell, and

this

for touch.”

McGrath laid the whip in front of the cross.

Ducane shuddered.

“And then there’s this,” McGrath was going on.

The candles curtsied in a movement of air and Ducane withdrew his attention from the whip.

McGrath, swollen to twice his size, seemed to be struggling with something or dancing, his hands raised above his head, casting a huge capering shadow upon the brick wall. Then with a heavy plop the garment fell into place and McGrath displayed it, grinning. He was wearing a vast cope of yellow silk embroidered with black fir-cones. With a coquettish movement he turned in a circle. The sleeves and trouser legs of his dark suit protruded from the exquisite cope with an effect of grossness. The garment was much too large for him. Radeechy had been a big man.

“This completes the get-up, you see.” McGrath had now produced a tall stiff embroidered head-dress rather like a mitre, and was about to put it on.

Ducane took it quickly out of his hand. “Take that thing off.”

“It’s posh, isn’t it?”

“Take it off.”

Rather reluctantly McGrath struggled out of the cope. As it came over his head he said, “Do you think I could have some of these things, Sir?”

“Have some—?”

“Well, as mementos like. Do you think I could have that cup thing?”

“No, of course not!” said Ducane. “These things are the property of Mr Radeechy’s heir. The police will take charge of them. Stand out of the way, would you. I want to look around.” He picked up one of the candles. “What a terrible smell.”

“I expect it’s the birds.”

“The birds?”

“Yes,” said McGrath. “The poor pigeons. See.”

He pointed into the darkness underneath a trestle table on the other side of the room.

Ducane moved the candle and saw beneath the table what looked like a large cage. It was in fact a cage roughly made out of a packing case and some strands of wire. Within the cage, as he leaned towards it, Ducane saw a spread-out grey wing. Then he saw a heap of sleek rounded grey and blue shapes piled together in a corner. The feathers were still glossy.

“All dead now of course,” said McGrath with a certain satisfaction. “Mr Radeechy wanted them alive.” McGrath’s hand reached out to touch the cage with an almost affectionate gesture. His wrist, woven over with golden wires, protruded a long way from his jacket.

“You mean—?”

“He used to kill them in the ceremony, whatever he did. Blood all around the place something shocking. It always took me quite a time to clean it up after he’d been having a go. He was very particular you see about the cleaning up.”

“Where did you get them?”

“Caught them in Trafalgar Square. Nothing’s easier if you get there early in the morning. Bit difficult in winter.

But I could usually catch one or two on a foggy day and carry them off under my coat.”

“And you kept them here?”

“Some at home, some here, till they were needed. I fed them of course, but they seemed to be asleep most of the time. Not having any light I suppose. I’d just put that lot in when it happened, about Mr Radeechy I mean.”

Ducane turned away from the little soft heap in the cage. “It didn’t occur to you to come down and let them out?”

McGrath seemed surprised. “Lord, no. I didn’t think of it. I didn’t want to come down here more than I need. And with poor Mr Radeechy dead I wasn’t going to trouble my head about a few pigeons.”

Ducane shook himself. The candlestick was beginning to feel very heavy in his hand. It tilted over and hot candle grease fell on to his wrist and on to the sleeve of his coat. He felt suddenly slightly faint and it came to him that ever since he had entered the room he had been becoming passive and drowsy. He had a distinct urge to remove the objects from the mattress and lie down on it himself. He wondered for the first time how the room was ventilated. There seemed to be very little air to breathe. He took a deep gasping breath and the smell sickened him and he gave a retching cough.

“Foul smell, isn’t it?” said McGrath, who was still on one knee beside the cage, watching him. “But it’s not just the birds, you know. It’s

him

.”

“Him?”

“Mr R. He smelt something awful. Did you never notice it?”

Ducane had in fact noticed that Radeechy smelt unpleasant. He had once overheard clerks in the office jesting about it.

“Well, if we’ve seen what there is to see we’d better go,” said Ducane.

He turned back to the altar. The golden cope with the black pine-cones had been tossed over one end of the mattress. Ducane saw in the close light of the candle that the cope was tattered and soiled, one wing of it darkened near the hem by an irregular brown stain.

“Is there anything else?”

“You’ve seen the lot, Sir. Look, there’s nothing else in the room. Just these tins, nothing more inside except some matches and some of Mr R’s cigarettes, bless him. Nothing under the tables except the old pigeons. But just you look for yourself, Sir, just you look for yourself.”

Ducane walked along the edges of the room with his candle and then turned to face McGrath who was now standing with his back to the tau cross, watching Ducane intently. Ducane saw that McGrath had picked up the whip and was teasing the slender tapering point of it with a finger of his left hand. McGrath’s eyes were empty featureless expanses of pale blue.

It’s the dreariness of it, thought Ducane, that stupefies. This evil is dreary, it’s something shut in and small, dust falling upon cobwebs, a bloodstain upon a garment, a heap of dead birds in a packing case. Whatever it was that Radeechy had so assiduously courted and attracted to himself, and which had breathed upon him, squirted over him, that odour of decay, had no intensity or grandeur. These were but small powers, graceless and bedraggled. Yet could not evil damn a man, was there not blackness enough to kill a human soul? It is in me, thought Ducane, as he continued to look through the empty blue staring eyes of McGrath. The evil is in me. There are demons and powers outside us, Radeechy played with them, but they are pygmy things. The great evil, the real evil, is inside myself. It is I who am Lucifer. With this there came a rush of darkness within him which was like fresh air. Had Radeechy felt this onrush of black beatitude as he stood before the cross reversed and rested the chalice upon the belly of the naked girl?

“What’s the matter, Sir?”

“Nothing,” said Ducane. He put the candle down on the nearest table. “I feel a little odd. It’s the lack of air.”

“Sit down a minute, Sir. Here’s a chair.”

“No, no. What are those odd marks on the wall behind you?”

“Oh just the usual things, Sir. Soldiers I’d say.”

Ducane leaned across the mattress and examined the white wall. It was a wall of whitewashed brick and the appearance of a wallpaper had been given to it by a dense covering of graffiti, reaching from the ceiling to the floor.

The customary messages and remarks were followed here and there by dates—all wartime dates. There were representations of the male organ in a variety of contexts. The decorated wall behind the cross provided a backcloth which was suddenly friendly and human, almost good.

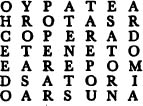

Then certain marks caught Ducane’s eye which seemed of more recent date, as if they had been put on with a blue felt pen. They overlaid the pencil scrawlings of the soldiers. There were several carefully drawn pentograms and hexograms. Then in Radeechy’s small pedantic hand was written

Asmodeus, Astaroth

, and below that

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of law

. Directly above the cross was a large blue square which Ducane, moving the candle nearer, saw to be composed of capital letters. The letters read as follows:

“What does that mean?”

“Lord, Sir, I don’t know. It’s in some funny foreign language. Mr Radeechy wrote it up one day. He told me to be careful not to smudge it when I was dusting.”

Ducane took out his diary and copied the square of letters down into the back of it. “Let’s go,” he said to McGrath.

“Just a minute, Sir,” said McGrath.

They were both leaning against the trestle table with the cross upon it. Lit by the candles behind it, the multiple shadow of the reversed cross flickered upon their two hands, McGrath’s left and Ducane’s right, which were gripping the edge of the trestle. McGrath was still holding the whip in his right hand, drooping it now against his trouser leg. Stooping a little, and with a delicate almost fastidious gesture, Ducane took the whip out of McGrath’s hand and swinging it round behind him tossed it on to the mattress. As his fingers touched McGrath’s he saw McGrath’s head and shoulders very clearly as if inscribed in an oval of light, the red-golden hair, the narrow pale face, the unflecked blue

eyes. The vision carried with it a sense of something novel. Ducane thought, I am seeing him for the first time as being young, no, no, I am seeing him for the first time as being beautiful. He tensed his hand upon the table, dragging his nails across the surface of the wood.

“Let’s not quarrel, Sir, shall we?”

“I wasn’t aware that we were—quarrelling,” said Ducane after a moment. He took a slow step backward.

“Well, there was that little business of ours, you know. You were kind enough to help me out with a little money, if you remember, Sir. And I was able to oblige you about the young ladies’ letters. I’d be most grateful, Sir, if we could now put this little matter on a proper business footing and then we can both forget all about it, see? I like you, Sir, I won’t make any secret of it, I like you, and I want us to be friends. Mr Radeechy and I were friends, like, and you and I could be friends, Mr Ducane, Sir, and that’s what I’d like best. There’s a lot I could do for you, Sir, if I was so minded, I’m a very useful man, Sir, and a jack of all trades if I may say so, and Mr Radeechy found me very useful indeed. I’d like to serve you, Sir, and that comes from the heart. But I think it would be nicer for us both if we just settled up the other little thing first of all. A matter of four pounds a week, say, not much, Sir, to

you

, I mean I wouldn’t want to charge

you

much. Just that, regular like—so perhaps, Sir, if you wouldn’t mind just filling in this banker’s order, I’ve always found that the easiest way—”

“A banker’s order?” said Ducane, staring at the apparition of McGrath flourishing a piece of paper in front of him. Then he began to tremble with laughter. One of the candles went out. “A banker’s order? No, no, McGrath. You’ve got it all wrong, I’m afraid. You’re a damnable villain but I’m not a total fool. I paid you a little because I needed you for this investigation. Now that you’ve done all you can for me I’m not paying you another penny.”

“In that case, Sir, I’m afraid I shall be forced to communicate with those young ladies. You realise that?”

“You can do what you like about the young ladies,” said Ducane. “I’m through with you, McGrath. The police will communicate with you about collecting up the stuff from here and you’ll be required to make a statement. You’ll

be off my hands, thank God. And I never want to see or hear of you again. Now we’re going back.”

“But, Sir, Sir—”

“That’s enough, McGrath. Just hand me the torch, will you? Now lead the way. Quick march.”

The remaining candles were blown out. The black door opened and let in the dark fresher air of the tomb-like passage. McGrath faded through the doorway. Ducane followed, holding the torch so as to illuminate McGrath’s heels. As he began to mount the ramp he felt a curious taste upon his tongue. He realised that at some point he must have put the half walnut absently into his mouth and eaten it.