The Norman Conquest (25 page)

Read The Norman Conquest Online

Authors: Marc Morris

Moreover, mounting a naval attack on England was not simply a matter of feasibility; there was, in addition, the question of obligation. According to Wace, those Normans who said that they feared the sea had also added ‘we are not bound to serve beyond it’. Why should the Normans follow their duke on such a patently hazardous adventure? We know that in general terms William’s subjects accepted that they owed him military service. The clearest statement of this fact comes in a document drawn up shortly after the Conquest (the so-called Penitential Ordinance) which refers at one point to those who fought because such service was owed.

25

Presumably these obligations in many instances had existed well before 1066, and explain in part how William was able to raise armies in the earlier part of his career. The frustrating thing is we don’t know on what basis military service was rendered. Historians used to argue that the Normans had a precociously developed feudal system, wherein many if not all major landowners recognized their obligation to serve the duke with a fixed number of knights. The problem is that there is virtually no evidence at all for the existence of such quotas prior to 1066.

26

The first time, in fact, that we get a clear indication of formal obligations being discussed is in 1066 itself, during the build-up to the invasion of England. Wace speaks of individual negotiations between William and each of his vassals, during which he begged them to render double what they normally owed and reassured them that this extraordinary service would not be drawn into a precedent. ‘Each said what he would do and how many ships he would bring.

And the duke had it all recorded at once, namely the ships and knights, and the barons agreed to it.’

27

This would all seem pretty thin – Wace was writing a century later – were it not for the fact that William’s written record, or at least a redaction of it, has survived. It amounts to a short paragraph of Latin, copied in an early twelfth-century hand, and it fills only a single page of a much larger manuscript. Historians call it the Ship List, because it is simply a list of fourteen names and the number of ships that each agreed to provide for William in 1066. For a long time it was regarded as inauthentic on the grounds that such precise statements of military service are otherwise unknown at such an early date. Nowadays scholars are inclined to regard it as a genuine resume of the arrangements made that year, drawn up very soon after the Conquest. In other words, it bears witness to a key moment not only in the preparation for William’s expedition but also in the development of the duke’s relationship with his vassals. The extraordinary demands of 1066 itself seem to have set the Normans on the road to the more exacting form of feudalism for which they are famous.

28

Precisely how William won over the more sceptical of his subjects is unknown. Wace has it that they were tricked into offering additional service by William fitz Osbern, who led the negotiations on the duke’s behalf. No doubt much was made of the injury to the duke’s right, the justice of his cause, and the permission he had obtained from the pope: if Malmesbury is correct about the timing of the assembly, William would have been able to display the papal banner and assure his audience that God was most definitely on their side. Certainly one of the inducements that was put forward to the Normans was the enormous material rewards that would come to them should the plan succeed. According to William of Poitiers, the duke pointed out that Harold could offer his men nothing in victory, whereas he, William, was promising those who followed him a share of the spoils. This may explain why, in the end, the Normans agreed to having the terms of their service written down, for the greater the service rendered, the greater the eventual reward.

29

It was one thing to pledge large amounts of service, another to deliver it. The figures listed on the Ship List must have been minimum requirements, but even so their scale impresses. William fitz Osbern and Roger of Montgomery, the duke’s intimate advisers since the

start of his career, both appear on the list, pledged to provide sixty ships apiece; William’s half-brothers, Odo and Robert, were respectively required to find 100 and 120. How these men, great as they were, proposed to procure these personal armadas is, like so much else, a mystery. The Bayeux Tapestry gives the impression that the entire Norman fleet was constructed from scratch. ‘Here Duke William ordered ships to be built’, it says, and immediately we see men with axes hacking down trees and shipwrights turning the timber into boats. Given the very large numbers required, and the very limited time available, we do not have to believe that every vessel was obtained in this way. The duke and his magnates must have had some ships of their own already to hand, and others could have been purchased or requisitioned, either in Normandy itself, or from places further afield, such as Flanders. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1066 there must have been much frenzied activity in the forests and shipyards of Normandy as men struggled to meet the demands of the duke’s great project that was now underway.

30

News of these preparations must have travelled quickly across the Channel – William of Poitiers tells us that Harold had sent spies to Normandy, and in any case activity on such a scale could hardly have been kept secret. By Easter, at which point the new English king returned south from his mysterious trip to York, fears of foreign invasion must already have been mounting.

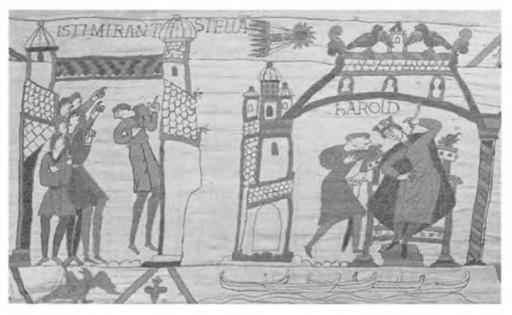

It was, therefore, unfortunate that his return to Westminster coincided with a rare celestial phenomenon. ‘Throughout all England’, says the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, ‘a portent such as men had never seen before was seen in the heavens.’ Every night during the last week of April, an extraordinary star was seen blazing across the sky. Some people, says the Chronicle, called it ‘the long-haired star’, while others called it a comet. It was, in fact, the most famous comet of all; the one which, six and a half centuries later, the astronomer Edmond Halley calculated came round every seventy-six years. But to men and women living through the uncertain events of 1066, it seemed wholly unprecedented, and as such was regarded as a terrible omen. ‘Many people’, said William of Jumièges, ‘said that it portended a change in some kingdom.’ On the Bayeux Tapestry, an anxious crowd of Englishmen point to the comet in wonder, while in the next scene King Harold is told what is evidently disturbing news.

Beneath his feet, in the Tapestry’s border, a ghostly fleet is already at sea.

31

And indeed, no sooner had the comet disappeared than news came that southern England was being attacked by a hostile fleet – but not a Norman one. The attacker was Harold’s estranged brother, Tostig, last seen being driven into exile as a result of the previous year’s rebellion. Precisely what he had been up to in the meantime is an insoluble mystery. A thirteenth-century Icelandic writer called Snorri Sturluson (of whom more later) maintains that the exiled earl travelled to Denmark and tried to persuade its king, Swein Estrithson, to help him conquer England. Orderic Vitalis, writing considerably closer to events, has it that Tostig visited Normandy and had actually returned to England as an agent of Duke William. Both these authors, however, make major factual errors in telling their stories, which should caution us against giving them too much credence.

32

All we can say for certain is what the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the

Life of King Edward

tell us: that when Tostig left England in 1065 he sailed to Flanders, where he was received by his brother-in-law, Count Baldwin. Most probably it was from Flanders that he launched his assault.

33

According to the Chronicle, Tostig and his troops landed first on the Isle of Wight, which they plundered for money and provisions, and then sailed eastwards along the coast, raiding as they went, until

they reached the port of Sandwich. Their wider objective is unclear. Possibly, in view of his rancorous split with Harold, Tostig was hoping to unseat his brother and replace him as king. More plausible, perhaps, is the notion that the younger Godwine was simply aiming to recover the estates and position he had lost the previous autumn, much as his father had done in similar circumstances fourteen years earlier, using almost identical tactics.

Whatever Tostig’s hopes might have been, they were ultimately dashed. Harold set out for Sandwich at once to confront his brother, and Tostig, hearing this news, put to sea again, taking with him the town’s shipmen. ‘Some went willingly, others unwillingly’, says the Chronicle, suggesting that enthusiasm for the exile’s cause, in the south at least, was at best mixed. Nor did his fortunes improve as he sailed north. Having reached the River Humber he raided southwards into Lincolnshire, ‘slaying many good men’ and perhaps intentionally trying to provoke his arch rivals, Eadwine and Morcar. If so he was not kept waiting long, for the two earls soon appeared leading land levies. Whether or not any actual fighting subsequently took place is unclear; the Chronicle says simply that the Mercian brothers drove Tostig out. Clearly one of the decisive factors that counted against him was the desertion of the press-ganged shipmen of Sandwich, and the extent of this haemorrhage is captured by the D Chronicler, who noted that the earl had sailed into the Humber with sixty ships, but left with only twelve. No doubt to his immense frustration, Tostig had found that support for his several rivals – Harold, Eadwine and Morcar – was far stronger than anticipated. From the Humber he sailed the remnant of his fleet further north and sought refuge with his sometime adversary, King Malcolm of Scotland.

34

Having successfully seen off his troublesome younger brother, Harold turned his mind to the far greater threat looming across the Channel, and began preparations to resist the planned Norman invasion. Tostig’s attack may have caused him to begin mobilizing his forces rather sooner than he might otherwise have done, and Harold, having arrived in Sandwich too late to intercept his brother, remained there waiting for his troops to muster. The reason for the delay may well have been the scale of the operation. ‘He gathered together greater naval and land armies than any king in this country had ever gathered before’, says the C Chronicle, clearly impressed.

Perhaps the host approached the notional maximum of 16,000 men that the recruitment customs recorded in the Domesday Book suggest. The gathering sense of national emergency, the fear of imminent foreign invasion, must have helped to swell the king’s ranks, and Harold, like English leaders in other eras faced with similar crises, no doubt played on such sentiments in his military summons. Several decades later John of Worcester penned a roseate picture of the king, for the most part formulaic in its praise, but probably authentic in recalling how Harold had ordered his earls and sheriffs ‘to exert themselves by land and sea for the defence of their country’.

35

Having assembled his host at Sandwich, probably in the month of May, Harold took the unusual decision to break it up again. As the Chronicle explains, the king decided to station levies everywhere along the coast.

36

Perhaps he feared that William, when he came, would repeat Tostig’s tactics, raiding along the shoreline in search of supplies and support. These troops would also have been able to provide an effective lookout for Norman sails, and no doubt there was some plan to enable the whole army to reassemble if a large enemy force made a landing. Harold himself sailed from Sandwich to the Isle of Wight (another decision possibly inspired by his brother’s attack) and established his headquarters there. Then he and the thousands of men spread out across England’s south coast did all they could do in such circumstances: they watched, and waited.

On 18 June 1066 William and his wife Matilda stood in the abbey of Holy Trinity in Caen, surrounded by a crowd of nobles, bishops, abbots and townspeople. It was the day of the abbey’s dedication, and we can picture the scene because it is described in a charter given on the day itself. Founded by Matilda some seven years earlier, Holy Trinity can hardly have been finished by the summer of 1066; as with Westminster Abbey a few months earlier, the rapid turn of political events had evidently prompted a dedication ceremony in advance of the church’s completion. Here was another public occasion for William and Matilda to demonstrate their piety, and to seek divine approval for the projected invasion. As the charter attests, as well as giving lands and rights to the new abbey, the couple also presented one of their daughters, Cecilia, to begin life there as a

nun. Nor was it just the duke and his consort making such donations: the charter (properly speaking a pancart) also records the gifts made to the abbey by several Norman magnates, and elsewhere in Normandy we can see other individuals making gifts to religious houses around this time as part of their spiritual preparations for the coming conflict. A certain Roger fitz Turold, for instance, made a grant of land to Holy Trinity in Rouen, confirmed by a charter which stated that he was ‘about to put to sea with Count William’. At some point during the summer, William himself gave a charter to the ducal abbey of Fécamp, promising its monks the future possession of land at Steyning in Sussex ‘if God should grant him victory in England’.

37