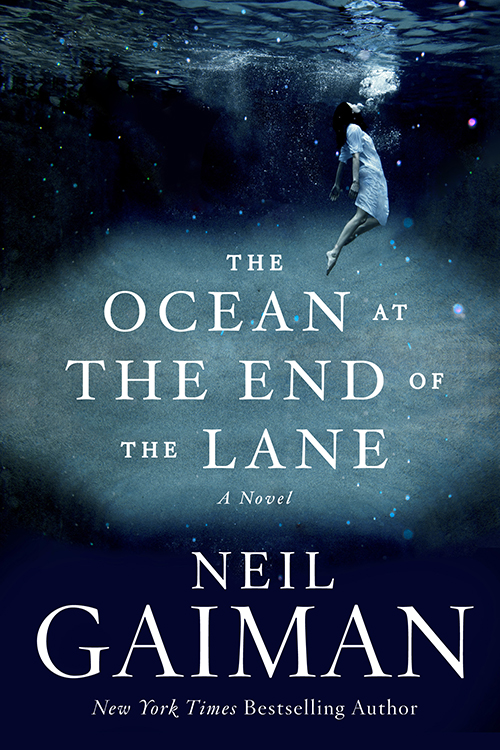

The Ocean at the End of the Lane

Read The Ocean at the End of the Lane Online

Authors: Neil Gaiman

The Ocean at the End of the Lane

Neil Gaiman

“I remember my own

childhood vividly . . . I knew terrible things. But I knew I

mustn't let adults know I knew. It would scare them.”

Maurice Sendak, in conversation with

Art Spiegelman,

The New

Yorker,

September 27, 1993

I

t was only a duck pond, out at the back of the farm. It wasn't very big.

Lettie Hempstock said it was an ocean, but I knew that was silly. She said they'd come here across the ocean from the old country.

Her mother said that Lettie didn't remember properly, and it was a long time ago, and anyway, the old country had sunk.

Old Mrs. Hempstock, Lettie's grandmother, said they were both wrong, and that the place that had sunk wasn't the

really

old country. She said she could remember the really old country.

She said the really old country had blown up.

I

wore a

black suit and a white shirt, a black tie and black shoes, all polished and

shiny: clothes that normally would make me feel uncomfortable, as if I were in a

stolen uniform, or pretending to be an adult. Today they gave me comfort of a

kind. I was wearing the right clothes for a hard day.

I had done my duty in the morning, spoken the words

I was meant to speak, and I meant them as I spoke them, and then, when the

service was done, I got in my car and I drove, randomly, without a plan, with an

hour or so to kill before I met more people I had not seen for years and shook

more hands and drank too many cups of tea from the best china. I drove along

winding Sussex country roads I only half-remembered, until I found myself headed

toward the town center, so I turned, randomly, down another road, and took a

left, and a right. It was only then that I realized where I was going, where I

had been going all along, and I grimaced at my own foolishness.

I had been driving toward a house that had not

existed for decades.

I thought of turning around, then, as I drove down

a wide street that had once been a flint lane beside a barley field, of turning

back and leaving the past undisturbed. But I was curious.

The old house, the one I had lived in for seven

years, from when I was five until I was twelve, that house had been knocked down

and was lost for good. The new house, the one my parents had built at the bottom

of the garden, between the azalea bushes and the green circle in the grass we

called the fairy ring, that had been sold thirty years ago.

I slowed the car as I saw the new house. It would

always be the new house in my head. I pulled up into the driveway, observing the

way they had built out on the mid-seventies architecture. I had forgotten that

the bricks of the house were chocolate-brown. The new people had made my

mother's tiny balcony into a two-story sunroom. I stared at the house,

remembering less than I had expected about my teenage years: no good times, no

bad times. I'd lived in that place, for a while, as a teenager. It didn't seem

to be any part of who I was now.

I backed the car out of their driveway.

It was time, I knew, to drive to my sister's

bustling, cheerful house, all tidied and stiff for the day. I would talk to

people whose existence I had forgotten years before and they would ask me about

my marriage (failed a decade ago, a relationship that had slowly frayed until

eventually, as they always seem to, it broke) and whether I was seeing anyone (I

wasn't; I was not even sure that I could, not yet) and they would ask about my

children (all grown up, they have their own lives, they wish they could be here

today), work (doing fine, thank you, I would say, never knowing how to talk

about what I do. If I could talk about it, I would not have to do it. I make

art, sometimes I make true art, and sometimes it fills the empty places in my

life. Some of them. Not all). We would talk about the departed; we would

remember the dead.

The little country lane of my childhood had become

a black tarmac road that served as a buffer between two sprawling housing

estates. I drove further down it, away from the town, which was not the way I

should have been traveling, and it felt good.

The slick black road became narrower, windier,

became the single-lane track I remembered from my childhood, became packed earth

and knobbly, bone-like flints.

Soon I was driving, slowly, bumpily, down a narrow

lane with brambles and briar roses on each side, wherever the edge was not a

stand of hazels or a wild hedgerow. It felt like I had driven back in time. That

lane was how I remembered it, when nothing else was.

I drove past Caraway Farm. I remembered being

just-sixteen, and kissing red-cheeked, fair-haired Callie Anders, who lived

there, and whose family would soon move to the Shetlands, and I would never kiss

her or see her again. Then nothing but fields on either side of the road, for

almost a mile: a tangle of meadows. Slowly the lane became a track. It was

reaching its end.

I remembered it before I turned the corner and saw

it, in all its dilapidated red-brick glory: the Hempstocks' farmhouse.

It took me by surprise, although that was where the

lane had always ended. I could have gone no further. I parked the car at the

side of the farmyard. I had no plan. I wondered whether, after all these years,

there was anyone still living there, or, more precisely, if the Hempstocks were

still living there. It seemed unlikely, but then, from what little I remembered,

they had been unlikely people.

The stench of cow muck struck me as I got out of

the car, and I walked, gingerly, across the small yard to the front door. I

looked for a doorbell, in vain, and then I knocked. The door had not been

latched properly, and it swung gently open as I rapped it with my knuckles.

I had been here, hadn't I, a long time ago? I was

sure I had. Childhood memories are sometimes covered and obscured beneath the

things that come later, like childhood toys forgotten at the bottom of a crammed

adult closet, but they are never lost for good. I stood in the hallway and

called, “Hello? Is there anybody here?”

I heard nothing. I smelled bread-baking and wax

furniture polish and old wood. My eyes were slow to adjust to the darkness: I

peered into it, was getting ready to turn and leave when an elderly woman came

out of the dim hallway holding a white duster. She wore her gray hair long.

I said, “Mrs. Hempstock?”

She tipped her head to one side, looked at me.

“Yes. I do

know

you, young man,” she said. I am not a young man. Not any longer.

“I know you, but things get messy when you get to my age. Who are you,

exactly?”

“I think I must have been about seven, maybe eight,

the last time I was here.”

She smiled then. “You were Lettie's friend? From

the top of the lane?”

“You gave me milk. It was warm, from the cows.” And

then I realized how many years had gone by, and I said, “No, you didn't do that,

that must have been your mother who gave me the milk. I'm sorry.” As we age, we

become our parents; live long enough and we see faces repeat in time. I

remembered Mrs. Hempstock, Lettie's mother, as a stout woman. This woman was

stick-thin, and she looked delicate. She looked like her mother, like the woman

I had known as Old Mrs. Hempstock.

Sometimes when I look in the mirror I see my

father's face, not my own, and I remember the way he would smile at himself, in

mirrors, before he went out. “Looking good,” he'd say to his reflection,

approvingly. “Looking good.”

“Are you here to see Lettie?” Mrs. Hempstock

asked.

“Is she here?” The idea surprised me. She had

gone

somewhere, hadn't she? America?

The old woman shook her head. “I was just about to

put the kettle on. Do you fancy a spot of tea?”

I hesitated. Then I said that, if she didn't mind,

I'd like it if she could point me toward the duck pond first.

“Duck pond?”

I knew Lettie had had a funny name for it. I

remembered that. “She called it the sea. Something like that.”

The old woman put the cloth down on the dresser.

“Can't drink the water from the sea, can you? Too salty. Like drinking life's

blood. Do you remember the way? You can get to it around the side of the house.

Just follow the path.”

If you'd asked me an hour before, I would have said

no, I did not remember the way. I do not even think I would have remembered

Lettie Hempstock's name. But standing in that hallway, it was all coming back to

me. Memories were waiting at the edges of things, beckoning to me. Had you told

me that I was seven again, I might have half-believed you, for a moment.

“Thank you.”

I walked into the farmyard. I went past the chicken

coop, past the old barn and along the edge of the field, remembering where I

was, and what was coming next, and exulting in the knowledge. Hazels lined the

side of the meadow. I picked a handful of the green nuts, put them in my

pocket.

The pond is next,

I thought.

I just have to go

around this shed, and I'll see it.

I saw it and felt oddly proud of myself, as if that

one act of memory had blown away some of the cobwebs of the day.

The pond was smaller than I remembered. There was a

little wooden shed on the far side, and, by the path, an ancient, heavy,

wood-and-metal bench. The peeling wooden slats had been painted green a few

years ago. I sat on the bench, and stared at the reflection of the sky in the

water, at the scum of duckweed at the edges, and the half-dozen lily pads. Every

now and again, I tossed a hazelnut into the middle of the pond, the pond that

Lettie Hempstock had called . . .

It wasn't the sea, was it?

She would be older than I am now, Lettie Hempstock.

She was only a handful of years older than I was back then, for all her funny

talk. She was eleven. I was . . . what was I? It was after the bad

birthday party. I knew that. So I would have been seven.

I wondered if we had ever fallen in the water. Had

I pushed her into the duck pond, that strange girl who lived in the farm at the

very bottom of the lane? I remembered her being in the water. Perhaps she had

pushed me in too.

Where did she go? America? No,

Australia.

That was

it. Somewhere a long way away.

And it wasn't the sea. It was the ocean.

Lettie Hempstock's ocean.

I remembered that, and, remembering that, I

remembered everything.