The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (18 page)

In attempting (what never should be attempted) a literal version of both the words and the metre of this poem, Professor Longfellow has failed to do justice either to his author or himself. He has striven to do what no man ever did well and what, from the nature of the language itself, never can be well done. Unless, for example, we shall come to have an influx of spondees in our English tongue, it will always be impossible to construct an English hexameter. Our spondees, or, we should say, our spondaic words, are rare. In the Swedish they are nearly as abundant as in the Latin and Greek. We have only ‘compound’, ‘context’, ‘footfall’, and a few other similar ones.

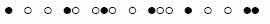

Longfellow’s

Evangeline

might be considered a more successful attempt to write English dactylic hexameter in the classical style:

This

is the

for

est prim

ev

al. The

mur

muring

pines

and the

hemlocks

.

Poe and modern English metrists might prefer that last foot ‘hemlocks’ not be called a classical spondee but a trochee. Those last two feet, incidentally, dactyl-spondee, or more commonly dactyl-trochee, are often found as a closing rhythm known as an

Adonic Line

(after Sappho’s lament to Adonis: ‘O ton Adonin!’ ‘Oh, for Adonis!’). The contemporary American poet Michael Heller ends his poem ‘She’ with an excellent Adonic line (or

clausula

, the classical term for a closing phrase):

And

I am happy, happier even then when her mouth is on me and I gasp at the ceiling.

‘Gasp at the ceiling’ is an exact ‘Oh for Adonis’ Adonic clausula. We shall meet it again when we look at Sapphic Odes in Chapter Three.

Robert Southey (Byron’s enemy) and Arthur Hugh Clough were about the only significant English poets to experiment with consistent dactylic hexameters: one of Clough’s best-known poems ‘The Bothie of Tober Na-Vuolich’ is in a kind of mixed dactylic hexameter. By happy chance, I heard a fine dactylic tetrameter on the BBC’s Shipping Forecast last night:

Dog

ger, cy

clon

ic be

com

ing north

east

erly…

By all means try writing dactyls, but you will probably discover that they need to end in trochees, iambs or spondees. As a falling rhythm, there is often a pleasingly fugitive quality to dactylics, but they can sound hypnotically dreary without the affirmative closure of stressed beats at line-end.

Bernstein’s Latin rhythms in his song ‘America’ inspired a dactyl-dactyl-spondee combination from his lyricist Stephen Sondheim:

I

like the

cit

y of

San Juan

I

know a

boat

you can

get on

And for the chorus:

I

like to

be

in Am

erica

Ev

erything’s

free

in Am

erica

.

You have to wrench the rhythm to make it work when speaking it, but the lines fit the music exactly as I have marked them. Amérícá, you’ll notice, has

three

stressed final syllables, a kind of ternary spondee,

tum-tum-tum

.

T

HE

M

OLOSSUS AND

T

RIBRACH

The

tum-tum-tum

has the splendid name

molossus

, like Colossus, and is a foot of three long syllables———or, if we were to use it in English poetry, three

stressed

syllables, . Molossus was a town in Epirus known for its huge mastiffs, so perhaps the name of the foot derives from the dog’s great bow-wow-wow. If a spondee, as Poe remarked, is rare in spoken English, how much rarer still is a molossus. We’ve seen one from Sondheim, and songwriting, where wrenched rhythms are permissible and even desirable, is precisely where we would most expect to find it. W. S. Gilbert found four triumphant examples for his matchless ‘To Sit in Solemn Silence’ from

. Molossus was a town in Epirus known for its huge mastiffs, so perhaps the name of the foot derives from the dog’s great bow-wow-wow. If a spondee, as Poe remarked, is rare in spoken English, how much rarer still is a molossus. We’ve seen one from Sondheim, and songwriting, where wrenched rhythms are permissible and even desirable, is precisely where we would most expect to find it. W. S. Gilbert found four triumphant examples for his matchless ‘To Sit in Solemn Silence’ from

The Mikado

.

To sit in solemn silence in a

dull dark dock

,

In a pestilential prison, with a

life-long lock

,

Awaiting the sensation of a

short, sharp shock

,

From a cheap and chippy chopper on a

big black block

!

The molossus, like its smaller brother the spondee, is clearly impossible for whole lines of poetry, but in combination with a dactyl, for example, it seems to suit not just Gilbert’s and Sondheim’s lyrics as above, but also call and response chants and playful interludes, like this exchange between Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader.

Why

do you

bo

ther me?

Go to hell

!

I

am your

des

tiny.

Can’t you tell

?

You’re

not my

fath

er.

Eat my shorts

.

Come

to the

dark

side.

Feel the force

.

As you might have guessed, that isn’t a poem, but a children’s skipping rhyme popular in the eighties. Lines three and four use a trochaic substitution for the dactyl in their second foot, but I wouldn’t recommend going on to a playground and pointing this out.

I suppose Tennyson’s

Break, break, break

At the foot of thy crags, O Sea!

could be said to start with a molossus, followed by two anapaests and a spondee.

If a molossus is the ternary equivalent of the spondee, is there a ternary version of the pyrrhic foot too? Well, you bet your boots there is and it is called a

tribrach

(literally three short). A molossus you might use, but a tribrach? Unlikely. Of course, it is very possible that a line of your verse would contain three unstressed syllables in a row, as we know from pyrrhic substitution in lines of binary feet, but no one would call such examples tribrachs. I only mention it for completeness and because I care so deeply for your soul.

T

HE

A

MPHIBRACH

Another ternary, or triple, foot is the

amphibrach

, though it is immensely doubtful whether you’ll have cause to use this one a great deal either.

Amphi

in Greek means ‘on both sides’ (as in an amphitheatre) and

brachys

means ‘short’, so an amphibrach is short on both sides. All of which means it is a triplet consisting of two short or unstressed syllables either side of a long or stressed one: --—-or, in English verse: . ‘Romantic’ and ‘deluded’ are both amphibrachic words and believe me, you’d have to be romantic and deluded to try and write consistent amphibrachic poetry.

. ‘Romantic’ and ‘deluded’ are both amphibrachic words and believe me, you’d have to be romantic and deluded to try and write consistent amphibrachic poetry.

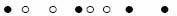

Ro

man

tic, de

lud

ed, a

tot

al dis

ast

er.

Don’t

do

it I

beg

you, self-

slaught

er is

fast

er

Goethe and later German-language poets like Rilke were fond of it and it can occasionally be found (mixed with other metres) in English verse. Byron experimented with it, but the poet who seemed most taken with the metre was Matthew Prior. This is the opening line of ‘Jinny the Just’.