The Ogre of Oglefort (2 page)

Read The Ogre of Oglefort Online

Authors: Eva Ibbotson

2

FINDING A FAMILIAR

T

he news that the Hag's familiar had gone on strike spread through the community of Unusual Creatures like wildfire. Gladys had never been popular, and now everyone was bitter and angry that the toad had deserted her mistress just before an important meeting.

The Hag's friends did their best to help. The fishmonger, whose mother had been a selkie (one of those people that is a seal by day and a human at night) took her into the shop and offered her the pick of his fish. Not the dead fish on the slab, of courseâa dead familiar would be very little useâbut the live ones in a tank that he kept for customers who liked their fish to be absolutely fresh.

“There's a nice flounder there,” he said.

But though flounders are interesting because they are related to the famous fish who reared out of the sea and granted wishes, the Hag was doubtful.

“It's really kind of you,” she said. “But fish are so difficult to transport.”

Two witches who worked as nannies, wheeling babies through the park, took her to Kensington Gardens because they had seen a Tufted Duck on the pond that they thought might be trained to be magical, but when they got up to it they saw at once that it wouldn't do. It was sitting on a clutch of eggs and looking broody, and one thing that familiars never do is sit on nests and breed.

The next day the Hag took a bus to Trafalgar Square, where she remembered having seen a pigeon with a mad gleam in its eyes. The Square was absolutely crammed with pigeons in those days, but though she paced backward and forward among the birds for a whole hour, she couldn't see that particular bird again.

“We'd better try the zoo,” said the troll. So on his afternoon off from the hospital they took the bus to Regent's Park.

For someone looking for a familiar, the zoo is a kind of paradise. There were lynxes and pumas and jaguars that seemed perfect, but the Hag knew that they would not be happy in the backyard of 26 Whipple Road, and though she was annoyed with Gladys, the Hag did not want her to be eaten.

There were cages of aye-ayes and lemurs and meerkats with huge eyes full of sorrow and strangeness, and there was a darkened room full of vampire bats and kiwis.

“A vampire bat would be wonderful,” said the Hag, and she imagined herself sweeping into the meeting with the bloodsucking creature dribbling on her shoulder.

But even in the zoo everything was not quite right. Not one of the creatures she saw really met her eye. The harpy eagles seemed to be half asleep; the serpents lay under their sunlamps and wouldn't move.

“Oh what is the matter with the world?” cried the Hag when she got home again. “It's as though nobody cares anymore. When I was young, any animal worth its salt would have been proud to serve a hag or a wizard or a witch.”

They were sitting sadly at the kitchen table when there was a knock at the door and Mrs. Brainsweller came to borrow some sugar.

“I've had so many funerals this week I hardly know which way up I am,” she said, “and it's made me all behind with the shopping.”

Mrs. Brainsweller was a bansheeâone of those tall, thin feys who wail when people die, and they are very much in demand at funerals. She could also levitate, that is to say she could float up to the ceiling and lie on her back looking down on the room, so she was a person who missed very little.

“You look a bit down in the mouth,” she said when the Hag had fetched the sugar. So they told her what had happened at the zoo.

Mrs. Brainsweller hit her forehead. “Of course, I should have thought of it sooner,” she said. “Bri-Bri will

make

you a familiar. There's nothing he couldn't do if he tried.”

The troll and the Hag looked at each other. Making familiars can be done, but it is very difficult magic indeed.

Bri-Bri was the banshee's only son. He was a wizard, a small man with thin arms and legs and an absolutely enormous head almost entirely filled with brains. His name was Dr. Brian Brainsweller and there was nothing he hadn't learned. He had learned spells for turning cows blue and spells for turning sausages into boxing gloves and spells for making scrambled eggs come out of people's ears, and he had seven university degrees: one in necromancy, one in soothsaying, one in alchemy, and four in wizardry.

But he didn't have any degrees in Everyday Life. Though he was thirty-four years old he was not good at tying his shoelaces or putting on his pajamas the right way around, and he would have eaten furniture polish if you had put it before him on a plate.

Fortunately this didn't happen because Dr. Brainsweller lived with his mother.

“What are you

doing

, Bri-Bri?” she would cry as he came down to breakfast with both his legs in one trouser leg, or tried to go to bed in the bath.

It was Mrs. Brainsweller who had seen to it that Brian took all his wizardry exams, and stopped him when he wanted to do ordinary things like riding a bicycle or eating an ice cream, because she knew that if you want to get to the top in anything you must work at it all the time.

The Brainswellers lived two doors down from the Hag's boardinghouse, and Brian had a workshop in the garden where he spent the day boiling things and stirring things and shaking things. Though he was shy, the wizard was a kind man, and he listened carefully, pushing his huge spectacles up and down, while the Hag and the troll explained what they wanted.

“Your mother thought you might make me a familiar,” said the Hag. “It could be something quite simpleâa spotted salamander perhaps?”

Dr. Brainsweller looked worried.

“Oh dear,” he said. “Of course if Mummy thinks . . . But I tried once and . . . well, come and look.”

He led them to a cupboard and pulled out a plate with something on it. It looked like a very troubled banana which had died in its sleep.

After that, the Hag lost heart completely. When she got back to her kitchen at Number 26, she found it full of friends who had come from all over the town to drink tea and tell her how sorry they were to hear of her trouble. A retired River Spirit, a man who now worked for the Water Board, offered to climb into the drains and look for an animal that had been flushed down: perhaps a water snake or a small alligator which someone had got for Christmas and didn't want anymore. But the Hag said it was now clear to her that she wasn't meant to have a familiar, and that the Powers-That-Be intended her to be shamed at the meeting, if indeed she went to the meeting at all.

And when all her visitors had gone, she put on her hat and smeared some white toothpaste on her blue tooth and left the house. She wanted to put magic and strangeness behind her and talk to someone who belonged to a different world. Someone completely ordinary, and friendlyâand young!

3

THE BOY

T

he Riverdene Home for Children in Need was not a cheerful place. It was in one of the most run-down and shabby parts of the city. Everything about it was gray: the building, the scuffed piece of earth which passed for a garden, the walls that surrounded it. Even when the children were taken out, walking in line through the narrow streets, they saw nothing green or colorful. Though the war against Hitler had been over for years, the bomb craters were still there; the people they met looked weary and shuffled along in dingy clothes.

Ivo had been in the Home since he was a baby, and he did not see how his life was ever going to change. He was not exactly unhappy but he was desperately bored. He knew that on Monday lunch would be claggy gray meat with dumplings, and on Tuesday it would be mashed potato with the smallest sausage in the world, and on Wednesday it would be cheese pieâwhich meant that on Wednesday the boy called Jake who slept next to him would be sick, because while cheese is all right and pies are all right, the two together are not at all easy to digest. He knew there would be lumps in the mashed potato and lumps in the custard and lumps even in the green jelly which they had every Saturday, though it is quite difficult to get lumps into jelly.

He knew that Matron would wear her purple starched overall till Thursday and then change it for a brown one, that the girl who doled out the food would have a drop on the end of her nose from September to April, and that the little plant which grew by the potting shed would be trampled flat as soon as its shoots appeared above the ground.

Ivo's parents had been killed in a car accident; there seemed to be no one else to whom he belonged, and he did his best to make a world for himself. There was an ancient encyclopedia in the playroomâa thick tattered book into which one could almost climb, it was so bigâand a well at the bottom of the sooty gardenâcovered up and long gone dryâbut sitting on the edge of it one could imagine going down and down into some other place. There was a large oak tree just outside the back gate which dropped its acorns into the sooty soil of the orphanage garden.

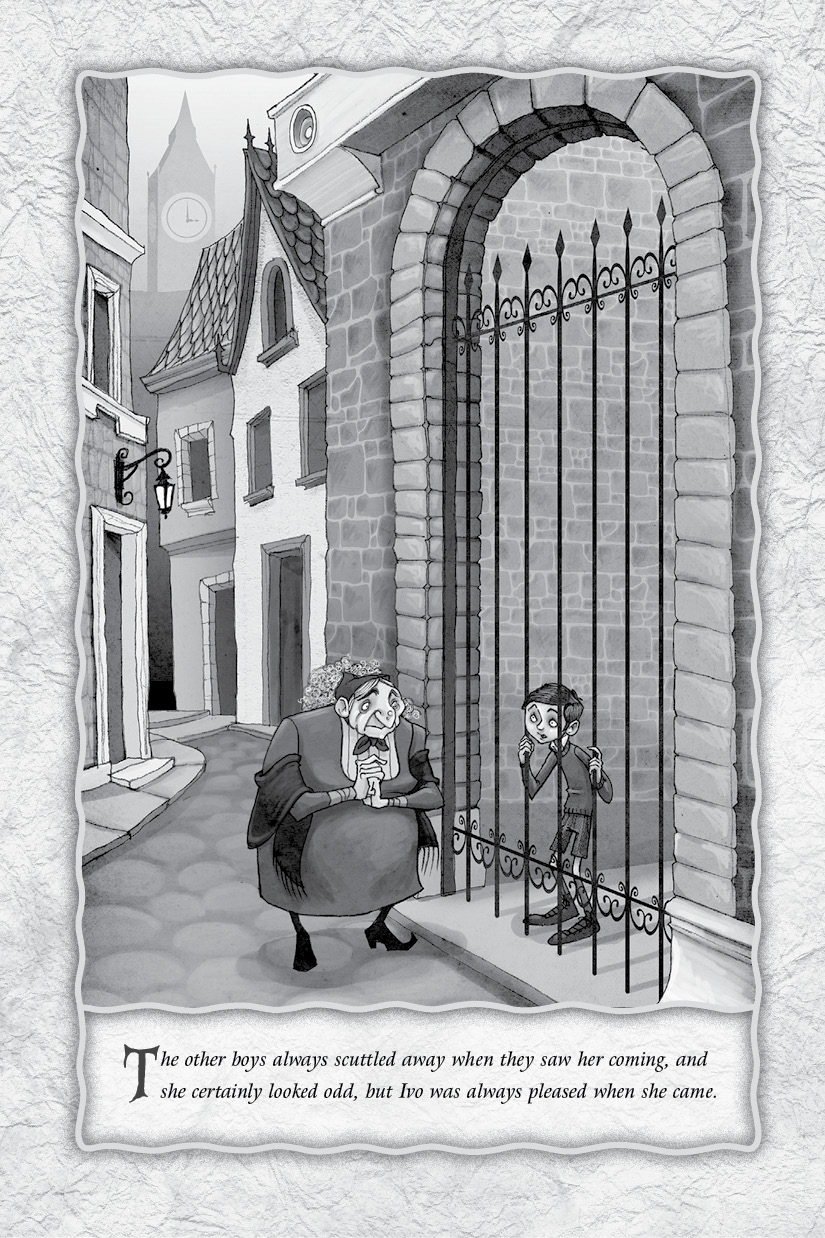

It was at the back gate that Ivo liked to stand, looking out between the iron bars onto the narrow street. Sometimes people would stop and talk to him; most of them were busy and only said a word or two, but there was one personâa most unlikely personâwho talked to him properly and who had become a friend. The other boys always scuttled away when they saw her coming, and she certainly looked odd, but Ivo was always pleased when she came. She was someone who said things one did not expect and he did not know anybody else like that.

The Hag did not have a grandson. She would have liked to have one, but since she had never married or had any children it was not really possible. But if she had had one, she thought, he would have been like Ivo, with a snub nose, a friendly smile, and intelligent hazel eyes. She had started by just saying hello to him on the way to the shops, but gradually she had stopped at the gate longer and longer, and they had begun to have some interesting conversations. Today, though, the Hag was so upset that she almost forgot she was talking to an ordinary human boy and one she had met only through holes in a gate, and almost straightaway she said: “I have had such bad news, Ivo! I have been betrayed by my toad!”

“By Gladys?” said Ivo, very much surprised. “But that's terribleâyou lived with her for years and years in the Dribble, didn't you? And you gave her your mother's name.”

“Yes, I did. You've no idea what I did for that animal. But now she won't do any more work. She says she's tired.”

There was a pause while Ivo looked at the Hag from under his eyebrows. He had guessed that Gladys wasn't just an ordinary pet, but he wasn't sure what he was supposed to know and what he wasn't.

“I don't understand,” he said. “I mean I thought . . . familiars . . .” He paused, but the Hag didn't snub him or tell him to stop. “I thought familiars didn't ever . . . I thought they served for life.” And under his breath, “I would if I was a familiar.”

The Hag stared at him. She had never actually told him that Gladys was a familiar, but she wasn't surprised that he had guessed. She had realized all along that he was a most unusual boy.

“They do. They're supposed to. And it's such a bad time . . .” It was no good holding back now. “There's a meeting . . . of the London branch of all the people who are . . . well . . . not ordinary. And some of them think they are very powerful and special and show off like anythingâeven though the world is so different for people like us. If I go without a familiar they'll despise me, I'm sure of that.” She sighed. “I suppose I must give up all idea of going. After all I'm so old and I'm an . . .”

She was about to say she was an orphan, but then she remembered that Ivo was an orphan, too.

But the boy was thinking his own thoughts.

“Can't you find another familiar?” he asked. “There must be lots of animals who would be proud to serve you.”

“Oh, if only you knew. I've been everywhere.” And she told him of all her disappointments.

There was a long pause. Then: “Why does it have to be an animal?” asked Ivo. “Why can't a familiar be a person? They're just servants, aren't theyâpeople that help a witch or a wizard?”

The Hag sighed. “I don't know where I'd get hold of one. And they'd have to be trained . . . Though I suppose if it was just for the meeting . . . It might be rather grand to sweep in with an attendant. But it's too late now.”

Ivo was grasping the bars of the gate with both hands.

“I could be one,” he said eagerly. “I could be your familiar. It says in the encyclopedia that they can be goblins or imps or sproggets, and they're not so different from boys.”

The Hag stared at him. “No, no, that would never do. You're a proper human being like Mr. Prendergast. It's not your fault but that's how it is, and you shouldn't get mixed up with people like us. It's very good of you but you must absolutely forget the idea.”

But Ivo was frowning. . . . “You seem to think that being a proper human is a good thing but . . . is it? If being a proper human means living here and knowing exactly what is going to happen every moment of the day, then maybe it's not so marvelous. Maybe I want to live a life that's exciting and dangerous even if it's only for a little while. Maybe I want to know about a world where amazing things happen and one can cross oceans or climb mountains . . . or be surprised.”

“You mean . . . magic?” said the Hag nervously.

“Yes,” said Ivo. “That's exactly what I mean.”