The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs (11 page)

Read The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs Online

Authors: Elaine Sciolino

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #History, #Biography, #Adventure

Jean-Pierre warned me off exterminators. He said they would overcharge and fill the apartment with toxic chemicals that wouldn’t do the job. He told me to lay down traps: either classic spring-loaded snap types that break a rodent’s neck or modern glue versions that “immobilize” but don’t immediately kill the beast. The first is quick and messy, the second slow and unnerving.

On the way to the hardware store for more information, I stopped at Guy Lellouche’s antiques store. “Put a piece of old Gruyère in a snap trap,” he said. He made a chopping motion with his hand. “Tack! The head will come off!”

If that didn’t work in two days, he said, try a finer cheese.

I was thinking more of a Maginot Line of steel wool. I had learned this battlefield tactic from the New York exterminator

who eventually rid us of our rat. You plug all the holes in your walls with steel wool, and hope that it will be too tough for mice to chew through. So at the hardware store, I loaded up with three grades of steel wool and a variety of traps: snap traps, glue traps, and little plastic “houses” that lure a mouse inside and shut the door after it. The guy in charge of pest-extermination products was dubious about steel wool. “Rodents have no bones,” he said. “They’re all cartilage; they can crawl through anything.”

“Of course they have bones,” I said. I had just read a story about the discovery in China of a 160-million-year-old fossil of a super-rodent.

I came back later in the day for more steel wool and proudly announced that I had laid down all the traps.

“You wore gloves, right?” he asked.

“You didn’t tell me to wear gloves.” I looked down at my hands.

“You always wear gloves,” he said. “Rodents are cunning. They can detect the smell of humans. If you didn’t wear gloves, your traps are useless.”

He told me to start over. And to use chocolate as bait. “Rodents like good chocolate,” he said.

“What kind of chocolate?” I asked. I had no idea that French rodents had such fine palates.

“Milk chocolate for mice,” he said. “Some even like meat. Butcher shops are full of rats.”

I headed to the butcher shop, where they thought my rodent problem was hilarious.

“You’re American, so use your gun!” said Sébastien, my favorite butcher. He pretended to shoot a rifle. “Poof! It’s dead.”

Maybe Sébastien would be my savior. “Are you a hunter? Do you know how to hunt mice?”

“The only thing I hunt is beautiful women,” he said.

The butchers got an even bigger laugh out of that. Then they sent me off to talk to the real rodent expert, Yves Chataigner, the cheesemonger two doors down.

When you’re in a war over who gets the cheese, it pays to be preemptive. Yves has a regular arrangement with a commercial exterminator. He advised me to put a small piece of aged Comté cheese on the traps. It costs about thirty euros a pound. He cut me a piece to taste and said there was no charge.

Why aged Comté, which is more expensive than young Comté or Gruyère?

“It’s got a good, strong rind,” he said.

“What’s rind got to do with it?”

A female customer jumped into the conversation.

“You have to have a strong rind and jam it in the trap at just the right level,” she said. “A smart mouse knows how to grab the cheese before the trap strikes.” Then she advised me never to buy ready-made glue traps but to make my own; she launched into a long, detailed explanation of how to construct them. She said that the pungent smell of old kitty litter might be effective—cat urine can be a powerful deterrent—and that barn owls can kill more than a dozen mice a night. I was out of my league. How did this woman, dressed in elegant white, know so much about rodents? “Ha, ha!” she laughed. “I’ve had a country house for years! You learn about rodents. You kill the rats, of course. But the mice! They’re rather sweet-looking. Just enjoy them.”

I should have known that the French would like rodents. A number of the fables of Jean de La Fontaine involve mice or rats,

which are often portrayed as kind, curious, and generous rather than dirty, disease-bearing, and disgusting. In “The Lion and the Rat,” for example, the rat displays patience and perseverance in saving the life of the King of the Beasts. In “The Cat and an Old Rat,” the experienced rat is too clever to be deceived by the cat’s tricks. In “The Rat and the Oyster,” the country rat “of little brains” shows gumption and curiosity in exploring the world, but his naïveté and innocence land him inside the oyster’s grip.

I tried to think of our French mouse as a small version of Remy, the anthropomorphic French rodent in the 2007 film

Ratatouille

. Remy appreciated good food and longed to cook. He was the secret “little chef” for Linguini, a garbage boy at a fancy Paris restaurant. Remy wanted to be a real chef, but he knew he would always be seen as a rat. “I pretend to be a rat for my father; I pretend to be a human through Linguini,” Remy says during one poignant moment in the film.

I didn’t get the chance to befriend our mouse. In the days that followed, it did not return. Ilda, the concierge, reported a sighting in one of the converted maids’ rooms on the sixth floor. Just like Remy in

Ratatouille,

it had good taste. It ate pistachios and a piece of chocolate cake but didn’t touch the garbage.

. . .

The other day when I was walking I got to thinking.

How do the French name their streets?

—A

RT BUCHWALD

,

AMERICAN HUMOR COLUMNIST

P

ARIS HAS MORE THAN SIXTY-TWO HUNDRED STREETS,

boulevards, avenues, and passages. Their names fall into several categories: kings (Henri IV, François I), American presidents (Wilson, Roosevelt), military victories (Iéna, Aboukir), important dates (September 4, after the day in 1870 when the Third Republic was created; November 11, after Armistice Day, marking the end of World War I), trades (bakers, drapers), about 175 saints (Jean, Paul, Georges), cities of the world (Tehran, Cairo, Rome), and the eccentric (Street of the Cat Who Fishes, Street of Bad Boys, Street of the Warmed Up, Street of the White Coats). “Street of the Martyrs” fits into the last category.

So who are these martyrs who deserved a street to be named after them? They seem to be everywhere. A pharmacy, a pastry

shop, a bistro, a men’s clothing boutique, and a mom-and-pop grocery store on the rue des Martyrs all have the word “martyrs” in their name. One of the street’s most popular breads is the

pain des martyrs,

a large, crusty, big-holed, white-and-whole-wheat loaf that never turns moldy. The street is so proud of its identity that for Christmas 2014 its merchants invested about 14,000 euros, along with 6,000 more from the local city hall, in new decorative lights for the street, including a huge banner in white that proudly proclaims, “Rue des Martyrs.”

The explanation about the martyrs turned out to be a long and complicated tale. The French are obsessed with history, partly out of a genuine affinity for the past, partly from a desire to cling to lost glory. Most people I asked had an answer to the question of how the rue des Martyrs got its name. And if they didn’t have an answer, they had a well-argued theory. The French learn in childhood that constructing a beautiful argument is more important than which side to take. Only the most self-confident confess to ignorance.

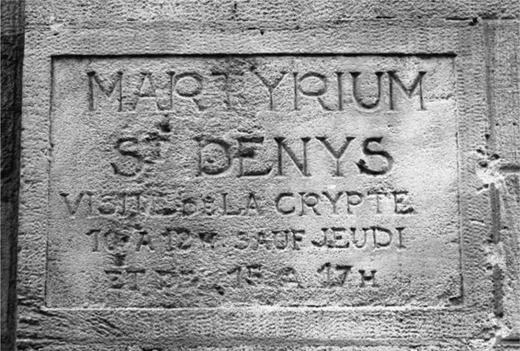

About one-third of the people I have asked about the martyrs had their story down cold. The name is rooted deep in Christian history and is so fantastical that even fervent Catholics find it hard to accept. The street’s martyrs are Saint Denis and his two companions, Rusticus and Eleutherius, who lost their heads for preaching the Christian gospel.

There are no surviving contemporary histories of Denis, only interpretations of his life over the centuries, none reliable. The dominant legend is set in the third century, when France was part of the Roman Empire. The pope sent Denis to what is now Paris to convert the pagan population to Christianity, at a time when Christians were a marginal cult. Denis built a church,

hired the clergy, smashed pagan statues, preached the Gospel, and made miracles. In modern parlance, he was a rock-star missionary.

Alarmed that they were losing ground to Jesus, pagan priests imprisoned the three Christians for refusing to accept the divinity of the Roman emperor. Many versions of what happened next appeared over the centuries. Denis and his companions refused to die, despite enduring a variety of tortures in prison. The most gruesome account of the tortures is described in an elaborate but fanciful ninth-century biography commissioned by Emperor Louis the Pious, the ruler of the Franks, and written by Hilduin, the abbot of the royal abbey of Saint-Denis, outside of Paris. Hilduin cared less about the truth and more about the creation of a cult of a patron saint to beat all others. In his telling of the tale, tabloid-style, Denis and his companions were beaten, roasted on a bed of iron, locked up with starving beasts, trapped in a blazing fire, and tortured on crucifixes. As happens with martyrdom, the trio’s luck ran out. To ready them for death, God sent Jesus and a multitude of angels to give them Holy Communion in prison. Then soldiers led them far from the city center, halfway up a hill north of the Paris city limits to Montmartre. They stopped before the Temple of Mercury at what is now the rue Yvonne-le-Tac, near the top of the rue des Martyrs. There, the executioners cut off their victims’ heads, using blunt axes to maximize their suffering.

Still, Denis held on. In a great miracle, and despite being ninety years old, he raised himself back to life. He cradled his head in his long white beard, washed it in a fountain, and carried it four miles north, to where he wanted to be buried, all the while accompanied by a choir of singing angels. But the

resurrection was only temporary. When he reached his destination, he surrendered to death once and for all. Hilduin’s biography was so full of plot twists, spine-tingling drama, and miracles that it is no wonder that until the French Revolution, it was considered the most influential version of the life of Saint Denis.

As for Saint Denis’s body, one version of the story is that he was buried at the site of his ultimate death by a pious but cunning Christian widow named Catulla. She is also said to have rescued the bodies of Rusticus and Eleutherius and reunited them with that of Saint Denis, so they all could rest comfortably together in peace. When the twelfth-century Saint-Denis Basilica was built there, it displayed what were believed to have been Saint Denis’s remains in reliquaries encrusted with jewels.

The fate of Denis’s head, meanwhile, became the subject of fierce debate in the Middle Ages. The clerics of Notre-Dame Cathedral claimed to have possession of his cranium; the monks of Saint-Denis insisted they had his entire head. The dispute ended up in a protracted, acrimonious public trial in the French Parliament in 1410; its outcome is unknown. Denis became not only one of the most revered saints in Christendom but also the patron saint of France. French kings and future saints, including Bernard, Thomas à Becket, Thomas Aquinas, Joan of Arc, Francis de Sales, and Vincent de Paul paid homage by walking in Denis’s footsteps up the route that is now the rue des Martyrs. It may be illogical, but the devout pray to him to relieve their headaches. (He is also the saint to call on if you need to be freed from strife or cured of frenzy, rabies, or possession by the Devil.)

IN MY NEIGHBORHOOD, SOME

people who know the legend sought to give it a rational explanation. Valérie Tadjine, the hairdresser at Franck Provost at the bottom of the street, said it was possible Saint Denis could have walked without his head. She described the chickens and ducks she saw as a child at her godmother’s house. “I saw their heads chopped off, but sometimes their nerves didn’t die,” said Valérie. “They’d run as far as . . . I don’t know . . . maybe as far as Montmartre!”

After a branch of the Belgian food chain Le Pain Quotidien opened on the rue des Martyrs, I asked Adeline Huré, a waitress in her twenties, if she knew the origin of the name. “Charlemagne came through here with the head of a decapitated king to the Saint-Denis Basilica,” she said, with great confidence. “There was a big hill and it is said that this was the hill of the dead, so he passed by with the head.”