The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs (19 page)

Read The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs Online

Authors: Elaine Sciolino

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #History, #Biography, #Adventure

Martine speaks slowly, never raises her voice, and seems unfazed by adversity, reacting calmly even when a Chanel coat

walked out the door with a shoplifter one day. When confronted with a mountain of clothes, she turns ruthless. I’ve seen her reject full suitcases, leaving the wannabe seller disappointed and humiliated. She has turned me down, more than once.

“You have to harden a little, get a little tough,” she said.

Toughness has helped Martine deal with the lost souls from the nearby single-room-only residence who wander into the shop from time to time. One regular is a singer-guitarist with a 1960s mind-set.

“He’s always dressed in a sort of sixties style,” Martine said. “He often talks nonsense, but it’s all sort of sprinkled with the names of bands and how it’s not the 1960s anymore. I think his mother was a singer in, like, the forties or fifties and she was really well known or something. When he’s feeling good, he puts his dentures in.”

She tells more stories: about the ex-con who threatened to take a coat without paying, the elderly woman who seemed ready to buy a gypsy-style skirt and then pulled a scam, the well-dressed adolescent pickpockets who carried tools to remove the anti-theft security devices from the clothing.

Serendipity rules. At Martine’s, I have found a Bruno Magli silver-and-black leather evening bag (twelve euros), purple suede Charles Jourdan flats trimmed in black leather (fifteen), a strapless flowered Yves Saint Laurent sunbathing top (twenty), and a short-cropped Max Mara wool crepe blazer (twenty). Just before my birthday one November, my daughter Gabriela spotted a sheared mink coat, with chestnut-colored skins so soft and lightweight that the fur felt like crushed velvet. Now, I have never been a mink coat kind of gal, but at fifty euros, and with the dead of winter coming, I was delighted to

accept it as a luscious birthday present from Gabriela and her older sister, Alessandra.

The best deal ever came the day I bought Hannah Vinter, the twenty-three-year-old daughter of a college friend, a welcome-to-Paris gift. A scarf with a red border and a lively pattern in olive, ocher, and teal called out to her from the two-euro bin.

When I went to pay for it, Olivia, the saleswoman, said it was five euros.

“But it was in the two-euro bin!” I protested.

“The tag says five euros,” Olivia replied. “It’s worth it.”

I almost didn’t buy it on principle, but I couldn’t disappoint Hannah. When we examined it closely back home, we discovered that it was signed “Hermès.” An Internet search identified it as a 1991 design called “Art des Steppes” by the artist Annie Faivre. Like the scarves that Guy Lellouche, the antiques dealer, and I had once traded, it had the hand-sewn edges with the hem rolled on the front side that proclaim Hermès authenticity.

The next time I was in the shop, I asked Olivia if she remembered the scarf. I told her it was an Hermès and asked whether the five-euro price tag had been a mistake. “Not at all!” she said. “It was a surprise. We like to do stuff like that.”

Finding an Hermès scarf in mint condition for five euros is the shopping equivalent of winning the lottery: it happens only once. So I didn’t tell Arianna the story; I promised nothing more than a bit of fun. We entered the store, and Dani Siciliano, an American singer-songwriter living in Paris, was helping out that day. I introduced them—first names only.

Chinemachine doesn’t get many celebrities. About the most famous customers over the years have been the American comedian Natasha Leggero and the British singer-songwriter Jarvis

Cocker. Dani flashed Arianna a glance of recognition but pretended oh-so-discreetly that she had no idea who she was.

Arianna, it turns out, is as relentless in sniffing out bargains as she is in running one of the world’s most successful online news aggregators. From the jewelry case, she chose two bold gold-toned 1960s-era chokers for twenty euros apiece. Then she spotted a ten-euro BlackBerry case in crocodile skin.

As we were about to leave, she saw a floppy straw hat in a soft yellow and taupe with a tiger-skin motif. She pulled it down low over her forehead and giggled. Arianna Huffington actually giggled. Okay, this wasn’t exactly the felt fedora Garbo made famous in the 1930s, but like the Garbo hat, it did disguise.

Arianna loved it. “I’m going to wear it now!” she said. “Let’s take a picture together behind the counter.”

Dani hesitated. Shoplifting is rife at Chinemachine, and Dani explained that inviting clients behind the counter was forbidden. But Arianna wanted to be part of the Chinemachine team.

“Oh, come on,” she insisted. “I want you in the picture, too.”

An offer Dani could not refuse.

“She knows how to be a really good troublemaker,” Dani recalled later.

The three of us posed behind the counter for Arianna’s selfie. We said our good-byes. It made me smile to see Arianna Huffington, a wealthy woman with polished skin and lacquered hair, head off to Charles de Gaulle Airport in a chauffeur-driven sedan wearing a ten-euro secondhand hat.

I have more fun in store for Arianna if she comes to town and wants to shop again. We will stop by No. 86 rue des Martyrs at By Flowers and say hello to the Israeli-born Paul Cohen and his twenty-something French business partner, Jonathan Winnicki.

There are few fancy designer names at this shop (although I once found a forest-green cashmere Burberry jacket for forty euros). It’s mostly clothes dating back to the 1960s and 1970s, many bought in bulk. You need time and stamina to discover gold.

Then we will go to the chicest shop on my secondhand tour: Troc en Stock, on the rue Clauzel just off the rue des Martyrs. The prices of the almost-new clothing are reasonable—about one-fourth to one-half of retail—and some items are real steals (a caramel-colored, soft-as-butter leather Fratelli Rossetti jacket for 140 euros and a Max Mara leopard-print silk blouse for forty).

There’s no negotiating with Sophie Meyer, the no-nonsense owner who opened the shop two decades ago. So I’ve tried to seduce her by bringing her bits of Coca-Cola memorabilia, which I know she collects, from the United States. We have developed a relationship of mutual respect, although I would never, ever have asked her for discounts. And then she started giving them to me.

My friend Susan, who hates shopping and spends a lot more money on Grace, her black Lab, than on her clothes, gave in to temptation during a visit to Paris and bought an entire dress-up wardrobe here: two clingy Diane von Furstenberg dresses, one Marc Jacobs black silk sleeveless shift, and a print Prada dress for everyday wear—for about the price of dinner for two at a two-star restaurant. (It helps that she’s somewhere between sizes 2 and 4.)

“We keep out the chain stores and preserve the feeling of neighborhood,” said Sophie. “And we’re cheaper than a psychiatrist.”

I know Arianna will like her.

. . .

There are two things you don’t throw out in France: bread and books.

—B

ERNARD

F

IXOT,

F

RENCH

P

UBLISHER

O

N THE THIRD SUNDAY OF EVERY MONTH, A SMALL

band of retirees takes over a corner of the rue des Martyrs. It’s time for Circul’Livre, a volunteer operation dedicated to the preservation of the book. The volunteers classify used books by subject and display them in open crates.

The books are free. Passersby may take as many as they want as long as they agree to an informal pledge to neither sell nor destroy them. They are encouraged to donate their own castoffs to keep the stock replenished. The volunteers affix a large sticker bearing the words “Circul’Livre” to the cover of every book, which curbs the resale impulse. The sticker is backed with superglue, which makes it virtually impossible to remove without damaging the cover.

When I moved with my family to Paris, we left most of our

books in storage. But I hated being without them. Surrounding myself with books makes me feel smarter. As Circul’Livre’s are free, I have become a bookaholic. I can arrive home with two shopping bags full of books. I hide them behind the living room couch if my husband is home, then cram them into corners of the shelves in our apartment. He calls it a sickness; I tell him collecting books is a lot cheaper than collecting Fabergé eggs or sixteenth-century Dutch prints.

I have found hardcovers of Henri Troyat novels, French versions of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books (leather-bound and gold-trimmed), cookbooks from the 1980s, and half of a ten-volume first edition of love stories in French history. Biographies of Jean-Paul Sartre, Brigitte Bardot, and Joan of Arc. Novels by Jacqueline Susann, James Michener, and Ernest Hemingway translated into French. In exchange, I have given Circul’Livre English-language novels in paperback, museum catalogs, publishers’ bound galleys, and years of

Foreign Affairs

. I know I get the better deal.

Circul’Livre was created in 2004 by a voluntary group in the working-class Twelfth Arrondissement. It now operates with teams in about eighty locations throughout Paris. According to its website, making friends is part of the exercise: “Circul’Livre is not satisfied with the promotion of reading; it is a powerful vehicle for social relationships in the neighborhoods.”

You can give the French no higher compliment than to call them intellectuals. I once went to a cocktail party and asked a French woman her profession. “Intellectual,” she replied. She was serious.

Circul’Livre is a group of intellectuals—not because they ponder Descartes or Rousseau in our neighborhood cafés but because they share ideas about books. They are masters of verbal

seduction, at using passion and politesse to begin a conversation that doesn’t want to end. Whether the subject is Diderot or turnips, Circul’Livre wants to talk about it.

We Americans often consider the French habit of verbal play a waste of time, because it doesn’t go directly to the point. But that’s precisely what makes this monthly event so much fun. It is about pleasure, not results.

Jérôme Perrin and Bertrand Morillon, Circul’Livre’s self-appointed “hosts” for our local branch, provide much of the banter. One Sunday, Jérôme picked up a book called

Philosophical Commentaries

and said, “Here you go. Here’s one for the beach!” Bertrand preferred the soft sell: “Régine Deforges! A great classic! Great to put you to sleep!” During the 1980s, Deforges became a best-selling author and was called the “high priestess of French erotic literature.” She could print books deemed offensive because she owned her own publishing house.

One Sunday, Jérôme told the crowd it was payback time. “

Chouquettes

! Won’t someone bring us

chouquettes

?” he asked. I ran over to the bakery and brought back two dozen small

choux

pastries sprinkled with sugar pearls. Jérôme gave me a double-cheeked kiss and handed me an espresso in a white Styrofoam cup.

The next Circul’Livre Sunday, I got so caught up in the frenzy of the book giveaways that I found myself on the volunteers’ side of the tables. As I hawked English-language books, Jérôme suggested that I come to one of Circul’Livre’s monthly meetings. But there are limits to acceptance. Andrée Le Faou, a retired office administrator and one of the volunteers, was not pleased. She took a long drag on her cigarette and said nothing. She may have even harrumphed.

Later in the day, I asked Andrée what was wrong. She told me

that only official members can stand on the organizers’ side of Circul’Livre tables. I had broken the rules. I told her I wanted to become an official member.

“We adore you, Elaine,” she said. “But our numbers are limited.”

So much for that.

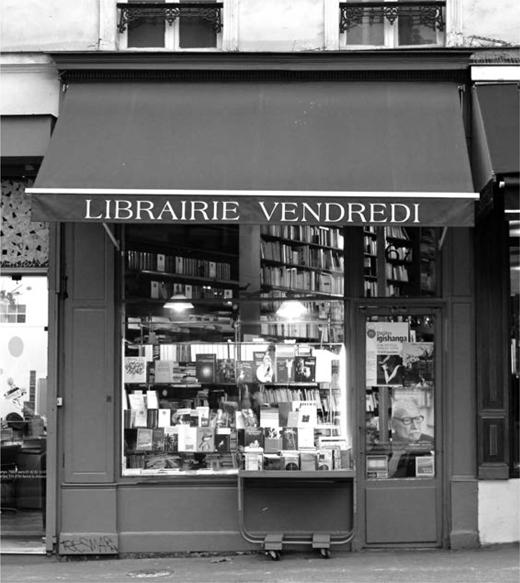

FRANCE RETAINS A REVERENCE

for the printed book. As independent bookstores crash and burn in the United States, the market here is healthier, largely thanks to government protections that treat the stores as national treasures. Grants and interest-free loans are available to would-be owners, and price-fixing reigns.

In France, booksellers—including Amazon—may not discount books more than 5 percent below the publisher’s list price. With such a small discount, many customers prefer to shop in stores, where book-loving salespeople stand ready to offer advice and opinions. E-books (whose prices are also fixed) have yet to become a big market, except for the French classics, many of which can be downloaded for free.