The Opal Desert (20 page)

Authors: Di Morrissey

âOh, Daddy. I'm sorry. The snake . . . I'm sorry.' Tears ran down her cheeks.

Albert reached out and took her hand. âHeavens, it's not your fault, sweet pea. You're far more important than opals and we had to get you into town.'

Shirley jumped to her feet, blazing with anger. âThey are bad men, bad. Let's find them. Let's go over there. Maybe Mr Gordon saw the bad men . . .'

Albert tried to soothe her. âNot right now. I can guarantee no one saw or heard anything,' he said in a resigned voice.

âBut how did they take it away? All the rocks? What about the ones we found, Daddy, that were in the bucket?'

âGone. They've taken the bucket, too. Would've been handy,' he said bitterly. âMost of my tools are gone, too.'

âCan we find some more opal?'

âI doubt it. I can see where the seam ran out. They've worked through the night and cleaned out the run.'

âWe still have our eggs, Daddy?'

He tapped the pocket of his work pants. âYes. We'll take them home and get them cleaned up.'

âMaybe something is left here . . .' She bent down and picked up a piece of clay from the top of the mullock heap.

âLeave it, Shirley.'

Albert drove the truck back over the rock-strewn terrain to where many of the miners had their camp. He jumped from the truck and strode towards one of the campfires.

âYou stay in the truck,' he told Shirley.

The men around the fire looked at him, their faces non-committal. Gordon tipped his hat back on his head.

âEvening. Care for a mug of brew?'

âNo, thank you, Mr Gordon.'

âHow's the little girl? We heard she was bitten by a snake. I seen a big 'un down a mine once,' said the man squatting next to Gordon.

âMy daughter is all right, but when I had to leave for town in a hurry, I didn't have time to secure my mine. When we got back, it had been ratted,' said Albert bluntly.

âYou bottomed on opal then?' queried Gordon.

âA decent patch. Now it's cleaned out.'

The men shook their heads. âDunno how that happened. Didn't see anyone around here,' said the man next to Gordon.

âDid any strangers come through? Did you hear anything? There's less than a quarter of a mile between here and my mine,' said Albert. âYou must have seen or heard something.'

âI hope you're not accusing us?' said Gordon, his face starting to redden.

âI'm simply asking if anyone knows anything before I report the theft to the police,' said Albert, turning as Shirley crept forward, putting her little hand into his. Albert glanced down at her. âI thought I told you to stay in the truck.' But his voice was gentle, so Shirley stayed.

âBetter ask Harry over there. His place is nearest yours,' said Gordon. He gave a shrill whistle. âHarry! Smoko!'

âDid you see the bad men who stole our opals?' Shirley asked Gordon.

âSorry, girlie. If anyone was in your mine last night, I don't know about it.'

Harry, known on the field as Hopeless, stuck his head out of his tent. âWhat's up?'

âThe Professor has a question for you,' said Gordon.

Harry clambered out of his tent and ambled across to them. âHeard you had to hurry into town yesterday. Snake, eh?'

âSeems news gets around. Did you also hear that I'd been ratted?' asked Albert.

âRatted, eh? Bastards. So you were on opal?' He glanced towards Albert's mine.

âSee anyone? Hear anything?' asked Gordon.

âIf I did, I wouldn't tangle with them,' said Harry. âCould be dangerous buggers.'

âBut if you heard something, surely you would have raised the alarm?' said Albert grimly.

âDunno. It wasn't till this morning I was told you and the girlie had gone to town. I thought you were working last night.'

âLast night? You heard working in my mine? I never work at night,' said Albert.

Harry shrugged. âGordon said you were heading back east soon. Thought you were having a last go.'

âDid you see anyone, a vehicle?' demanded Albert.

âHeard a truck. Thought you were coming back and working. None of my business,' said Harry.

Albert stared at the tightly closed faces of the men.

âI see. I hope that if any of you get ratted, your mates will be as helpful as you have been to me. Come on, Shirley.'

Shirley and her father climbed back into the truck and Albert drove towards their tent.

âDid those men steal our opals, Daddy?'

âI don't know. But they knew it was going on.'

âAre we going to tell a policeman?' asked Shirley.

âI'll report it, but it won't do much good. I'll speak to some of the fellows in town who buy rough and nubs, just in case. But I don't think our opals will be offered around here. Never mind, we'll just have to make the best of it.'

Shirley heard the frustration in his voice and said sadly, âI'm sorry, Daddy. 'Bout the snake.'

âOh, sweet pea, I've told you before. It wasn't your fault. These things just can't be helped. Main thing is, you're all right.' He paused. âI know one thing for sure, though. As soon as we leave the camp, there'll be a bunch of new claims pegged near our mine.'

âWhat are we going to do, Daddy?'

âWe're going home to see Mummy and baby Geoffrey and sell those nobbies and start somewhere else next holidays. That's what we'll do.'

âWill we find more opals in our new mine?' asked Shirley dubiously.

âYou know, I think we might try a new place. I've heard about another spot, Opal Lake. Tucked away, past White Cliffs. Might try our luck out there, eh? We both have to work hard at school and then we'll be off. We'll start over, Shirley. If you get knocked down, you get up and start again.'

They packed up their tent and loaded their things into the back of the old truck. As they left, Shirley bent down and picked up a stone and put it into her pocket. It was valueless but it would remain with her for years as a talisman and a reminder that life was not always fair and just.

On the long drive back to the city, Shirley fingered the five beautiful nobbies. Her father told her opals were like a fire that spread and ate you up. Once seen, never forgotten. Like a warm fire on a cold winter's night, they drew you to their fierce and alluring flame. Maybe in this place called Opal Lake they would find more of them.

I

N THE MOONLIGHT THE TWO

figures, etched black against the silver stretch of the still lake, stood transfixed.

âRemember tonight, Shirley. It might be a long time before you see it like this again,' said Albert softly to his daughter.

âIt's like a picture from my fairytale book,' said the little girl, holding her father's hand.

âThe big rain this winter finally reached Opal Lake.

I don't expect it's been like this for a long time.'

âBut it is a lake, so it should have water in it,' said Shirley.

âOut here, in the west, it's very dry and the water only flows after massive rains. It's not often that it gets as far as this lake.'

âCan we stay here till the morning? I want to see it in the daytime.'

âYou bet. We can throw down our sleeping bags and I'll fetch some wood and light a little campfire.'

Shirley sighed. âI'm so glad we came here, Daddy. This is much nicer than that camp at Lightning Ridge.' She stopped, sorry that she'd reminded her father of their ratted mine. Her father had promised he'd find a new place to mine. She hoped these holidays would be better than the last ones. Shirley had worried that her mother wouldn't let them come away again after the episode with the snake, but her mother had been pleased with the beautiful nobbies they'd found, and whatever her father had told her had appeased her enough that she agreed to their coming on another trip.

âI'll get my bag. Are we going to live out here?' asked Shirley, heading for their truck.

âNot here at the lake. Tomorrow we'll head into town and get our claim organised.'

Together they sat at the edge of the shimmering lake, the light from their campfire dancing on the surface of the shallow water.

âIt looks really deep. Could there be a huge monster down below, like a dinosaur?'

âNot any more, sweetie. They were here a long time ago.'

âI'd love to see one,' sighed Shirley.

âWell, in the morning we'll have a good look at the lake and see what's out there. Now you snuggle down. It will get chilly later, so I'll put another log on the fire. When we wake up, we'll watch the sun rise. How special will that be?'

âIt'll be good, Daddy. Night, night.'

âSleep tight, sweet pea.'

Shirley wriggled into the kapok padded bag and curled up like a fat caterpillar beside her father. He lowered a log into the embers of the fire and together they watched its small red sparks flare into the sky, matching the stars for brilliance. Sleepily Shirley watched these red jewels sparkle and disappear. They reminded her of the red fire that danced in the heart of opals. She hoped this new place would lead them to more beautiful opals. But for Shirley it was also very, very special to be so far away from home, alone with her father in such a magic spot. She knew she'd always remember this time.

The smell of the fire and the crackling of wood woke her. It was still dark, but the sky was tinged a deep indigo, so she knew that daylight was not too far away. From the warmth of her cocoon she watched her father throw tea leaves into the bubbling billycan. Seeing she was awake Albert smiled at her and lifted the billycan with a thick rag. With an extended arm, he swung the pot of brew around in a circle.

âThat'll settle the tea leaves,' he said.

Shirley laughed. âDo it again, Daddy.' She loved it when her father did one of his campfire tricks.

They toasted thick chunks of bread on a stick and smeared them with golden syrup.

âHere they come, the bridesmaids dancing attendance on the queen, leading her towards her throne in the sky,' said Albert, pointing to the horizon. âFirst the ladies in lilac, then rosebud pink and then pale gold.'

Shirley watched the sun rise, its colours running together more quickly, as a cloud of deep scarlet began staining the low sky. âThere it is,' she cried excitedly as the first gold rim of the day glinted over the horizon.

Hugging their mugs of tea, father and daughter sat, dwarfed by the enormity of the pageant marching across the sky. But they were not the only audience. Seemingly from nowhere, thousands of birds began to awaken.

âHow do they know about the lake?' whispered Shirley as small birds flitted, others screeched and called, and â presiding over them all â pelicans glided and then splashed to a skidding halt in the shallows. The sky had suddenly come alive with darting birds, and the shining surface of the lake was ruffled as they jostled to find their own stretch of glistening water.

âUnbelievable,' sighed Albert. âWhat a magnificent sight. They must have come from miles away. They know, they just know about the water. I don't know how, but it's wonderful.'

After breakfast, as the novelty of the scene wore off, Shirley raced through the shallow water, laughing joyously as flocks of birds rose and resettled. She waded far out into the lake, heeding the warnings of her father to watch out for submerged logs.

âIt's so clear, Daddy. I can see everything on the bottom. There's little funny fish in here, too. And tadpoles.'

Eventually Shirley was persuaded that it was time to leave and push on to the tiny township of Opal Lake to find somewhere to stay, get supplies and then take up their claim.

âI've only seen markings on a map, so I don't know what to expect,' Albert told Shirley as the old truck churned through the soft soil towards the faint tracks through the scrub.

The sun was high and hot by the time they saw the small hills and cluster of buildings that marked the little town. Beside one rise they saw what they realised was a deep mine because of its large mullock heaps. On the hills they could see diggings that signified a rabbit warren of mines burrowed into the hillside.

âLooks a bit different from the Ridge.'

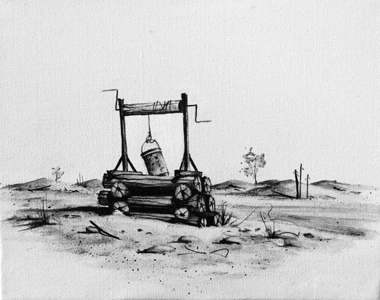

âI don't see many camps,' said Shirley. âAnd that windlass has two handles.'

âI think that the people here live in their mines rather than in camps,' explained her father.

âDo we have to live in our mine as well?' asked Shirley dubiously.

âWe'll be all right in our tent for a bit, but who knows? We might dig out a house in no time at all,' said Albert.

âWhat if there are opals?' asked Shirley. Then with her eyes alight she added, âCould we have a house with the roof and all the walls and floor made of opal?'

Her father laughed. âAnd anytime you needed money you could just polish the floor by scraping off a layer of gemstone. That's a nice fairytale.'

They stopped at the hotel and introduced themselves. Albert was pointed to the general store where the miners' licences were checked and lodged, and he was given a rough map and a lot of advice.

âHow many miners working out here?' he asked.

âAw, thirty or so,' answered the storekeeper. âIf you're after lodgings, there's a boarding house out at the open-cut. It's basic underground accommodation. Looks a bit like a Roman bath house.' He grinned. âBut it's comfortable enough and Mrs O'Brien cooks for those that want some tucker. We're a good little community. Some are just passing through, but most miners have been here a decent while, times being what they are. We look out for one another.' And he added, âTroublemakers aren't welcome.'

âI'm pleased to hear it,' said Albert. âWe plan on camping on our claim eventually but maybe for a night or two we'll try the boarding house.'

Shirley was entranced by the doors leading beneath the now abandoned open-cut mine. The boarding house was a basic place. Hollowed-out caverns were turned into rooms, each with a bed, table and shelves. It was relatively clean, if a little dusty and smelling of earth. Mrs O'Brien cooked outside under an iron-roofed shelter and most people ate at the roughly made wooden table.

They spent two days there and while Shirley was itching to get to their claim and set up their tent, Albert found the time at the underground lodging useful. People were friendly and forthcoming about recent strikes, shared rumours about new fields and the merits of the various buyers who came to Opal Lake. Mrs O'Brien spoilt Shirley with biscuits and one of the men gave her a small light stone that had a decent bit of colour in it. Shirley was polite and thanked him, but she knew that it could not be compared with the black opal her father had found at Lightning Ridge and asked Albert why this opal looked different.

âThat's because it was formed in a different sort of rock,' explained her father. âIn Lightning Ridge, the rock is mostly sandstone and the opals are sandwiched between its layers, so that's the only place we find the black opals with the brilliant dark colours and red fire flash in them. Out here, the rock is limestone and it contains a lot of a mineral called calcium. So here, at Opal Lake, we get the light crystal opal, sometimes with lovely colours.'

âBlue and green and gold,' said Shirley.

âBut no fire in the stones. The other wonderful thing about calcium deposits is that they can contain lots of fossils, which might become opalised.'

âAre there bones here too?' asked Shirley, thinking of long-dead dinosaurs.

âYou never know,' said Albert with a smile.

âWell, I like all opals,' said Shirley firmly.

They set up their tent and campsite on their allotted square, which was a decent-sized claim. What they both also liked about it was the fact that it was on top of the hill with a view all around. Albert immediately levelled the area and started digging straight into the hillside, working back towards the centre of the hill, as others near him had done. A large burly man with a bushy beard and a heavy foreign accent came over and announced that he was Ivan, their neighbour, and offered to show them around his mine.

âI have been here two years,' he said. âFrom Russia. I lost my family in the revolution and so I came here. This land is good to me.'

âHave you found any opals?' asked Shirley.

âShirley, you know that it's rude to ask such questions,' remonstrated her father.

Ivan smiled. âI have a few. Enough to keep me going. But perhaps I do not explain myself well. This land is good to me because it is a healing place. It is good for my soul. But you are right, little one. We all hope for a big strike so we keep digging. I have made a room as big as a ballroom in the palace in Leningrad.' He chuckled. âDo you plan to live out here?' he asked Albert, glancing at Shirley.

âOnly in the school holidays. I'm a schoolteacher. But if Opal Lake is as nice as it seems, we'll come as often as we can whether we find opal or not.'

âAnd if we make it really nice, Mummy and Geoffrey can come too,' added Shirley.

âIf you need any help, I am at your service,' said the big Russian.

âThat's very kind of you,' said Albert.

The other locals were equally hospitable, without being intrusive. Indeed, Albert and his daughter felt part of this small community in a very short time, sharing with the other inhabitants the privations and pleasures of life in a remote dot of landscape, united by their dreams of finding the precious gem.

So when Albert hit a small patch of relatively good opal, everyone was pleased for them. Although the seam petered out quickly, the burst of excitement created by his find raised everyone's hopes.

âWhen we sell the opal what will we do with the money?' Shirley asked her father.

âNot everything we find is going to end up being sold. The buyer only offers us a price based on what he thinks can be cut from our rough. He has to take a bit of a punt. But he'll make a fair offer for the bulk of our parcel,' said Albert confidently, and resumed swinging his pick.

The limestone was firm and solid and the mine didn't need wooden supports or a pillar in the central area to hold up the roof. But one day, as he tunnelled towards the west of the mine, Albert's pickaxe hit a point that was fragile and a seam suddenly split and opened up, rocks, clay and debris spilling into the drive.

He jumped back as Shirley cried out in alarm, âRun, Daddy!'

âI'm all right, possum.' He headed back into the small cavern where Shirley had been filling a bucket. âBut I don't think we'll work down in that direction anymore. There seems to be a problem along there that we'd be better off not digging into.'

Albert and Shirley had decided on a plan for their dugout. Essentially it was a simple design with a main central room and a couple of smaller basic ones on the eastern side, with a bit of terrace out in the front from which to survey their view. They decided that if an opal find led in another direction, they would just have to build an additional drive.

The nights were cold so, when the mine was big enough, Albert dragged their sleeping bags into the entrance. There they were warmer and could still look out at the deserted landscape below, stark in the starlight. Occasionally a dingo howled. Sometimes in the morning, they found the footprints of a goanna that had been prowling for any scraps in their camp. In spite of her encounter with the snake, Shirley was unafraid of the lizards that roamed the arid country around them. Some of them were dainty, little bright-eyed ones, but others were larger, like the bearded dragons.