The Orphans' Promise

Read The Orphans' Promise Online

Authors: Pierre Grimbert

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Family Saga, #World Literature, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Magic & Wizards, #French, #Fiction, #Sagas, #Fantasy, #Epic, #Coming of Age

Also available in The Secret of Ji series:

Six Heirs

Forthcoming:

Shadow of the Ancients

The Eternal Guide

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 2013 Pierre Grimbert

English translation copyright © 2013 by Matt Ross and Eric Lamb

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

The Secret of Ji 2: The Orphans’ Promise

was first published in 1999 by Les éditions Mnémos as

Le Secret de Ji, volume 2: Le serment orphelin

. Translated from the French by Matt Ross and Eric Lamb. Published in English by AmazonCrossing in 2013.

Published by AmazonCrossing

ISBN-13: 9781477808863

ISBN-10: 1477808868

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013908851

CONTENTS

BOOK III: THE JUDGMENT OF ZUÏA

SHORT ANECDOTAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE KNOWN WORLD

Author’s Note

At the end of the book, the reader will find a “Short Anecdotal Encyclopedia of the Known World,” a glossary that defines certain terms used by the narrator and provides supplementary details that don’t appear in the story, without giving the story away, of course—far from it!

Therefore, the reading of the “Short Anecdotal Encyclopedia” can be done in parallel with the story, at moments the reader finds opportune.

PROLOGUE

P

raised be Eurydis. May her teachings serve you well.

Before the gods, my name—the one I was given when the sun rose on my first day in this world—is Lana Lioner of Ith, daughter of Cerille and Lioner.

Quite a big name for such a small thing, as Maz Rôl had the habit of saying when he wanted to tease me. And yet, he was the one who lengthened it further by adding the title, Maz. Fortunately, people simply call me Maz Lana, even if this invented title draws avowals of respect and deep admiration that I don’t deserve; only the gods are worthy of that kind of esteem. But this is hardly the subject that preoccupies my thoughts right now. I could always debate this question with a circle of students, if I am ever given the opportunity to teach again.

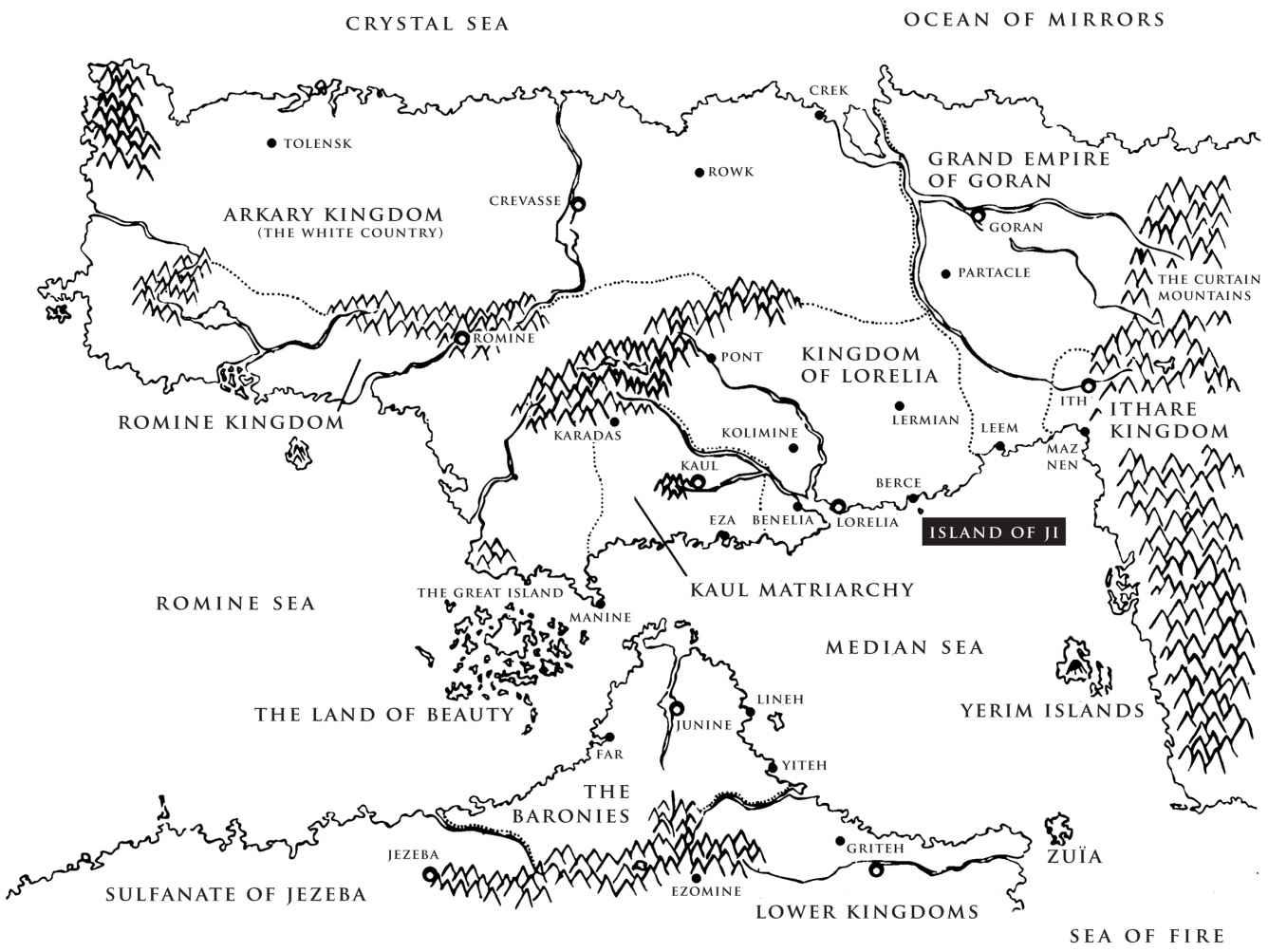

I am a descendant of Maz Achem d’Algonde of Ith, who carried out the duties of ambassador for the Grand Temple to the Grand Empire of Goran between the years 760 and 771 of the Eurydian calendar. The post was very important and was held in high esteem by the Temple’s administration, and was typically seen as a step on the way to being anointed an Emaz. But despite his title, my ancestor’s name is rarely spoken without a certain malaise.

When my parents spoke about an ancestor from one of their lineages, it was always with praise, pride, and nostalgia. There were several Maz in our bloodline, as well as a few Emaz, and they all left their mark on the history of the Holy City. There were war chiefs as well, fierce soldiers and ambitious conquerors from a past just as distant as it was grim. They were all alluded to with respect, and the paths they followed, however wrong they may have been, followed the dominant mores of the era.

My great-grandfather Maz Achem was the only one mentioned as a necessary link in the chain, a piece connecting these prestigious ancestors to the more recent generations, a piece which would have been happily removed if it were possible. We never spoke about his actions, his life, the trace he left in the world, and especially avoided his relationship with the universal quest for Eurydis’s Moral.

Of course, as a child I hardly thought twice about it. But growing up, this omission began to intrigue me, and I eventually questioned my parents. Although still young, I could easily tell that my question put them ill at ease. Which merely piqued my curiosity, for I had gotten used to getting all the answers I wanted. There was no subject of conversation that was off-limits in our household—a principle I held dear and that I continued to apply with my circle of students.

After some hesitation, my father answered me, choosing his words in such a way that they were neither disrespectful nor scornful. That’s the impression of Achem that his story left…

Although he had dedicated the greater part of his early life to studying and teaching the Goddess’s Moral, as was his duty, during his later years, Maz Achem had changed drastically. He had become a dissenter, a reformist guilty of several immoral acts. The first of which was the abandonment of his post as ambassador to the Grand Empire—a decision he made without even announcing it to the Temple, and which he never explained.

Upon his return to Ith, he seeded disorder in several gatherings of Emaz, going as far as to persecute the great priests in their own temples. This conduct alone would have been enough to discredit him, but what

drove him to these extreme acts was even worse—on the verge of sacrilegious. He absolutely insisted that others listen to him. But all the Emaz had already heard enough. Achem was asking the great priests to make a profound modification in their interpretation of certain precepts of the Moral of Eurydis. However, he himself recognized his inability to present any convincing argument. If he indeed had reasons, Maz Achem never provided them.

Of course the Emaz priests refused, encouraging him to return to ideas more in line with those of the Temple.

He persisted in his efforts, though, embarking on a campaign of public speeches in which he presented his theories, even though they had already been judged as antithetical to the Moral by the wisest of our wise, despite Maz Achem’s esteemed position.

Faced with his obstinacy, the Emaz had no other choice but to declare him a heretic—the highest dishonor—and to revoke his title of Maz, something that has only occurred four times in our history. Their punishment at least had its anticipated effect: Achem ended up abandoning his futile and harmful crusade and left to settle in Mestèbe, where he died a few years after, never again attempting to corrupt Eurydis’s teachings.

My father had nothing else to add. He asked me if I had learned something from the story, as if he had just told me a simple religious fable. I said I had and made a vow to never betray Eurydis’s Moral, which is what he expected of me. Still, I was perplexed.

Up until then, everything that I had been taught rested on these three values: Knowledge, Tolerance, and Peace. The three virtues of the wise ones. The three steps to climb to reach the Moral.

During my ancestor’s era, hadn’t the Emaz disregarded one of the first two? Weren’t Achem’s ideas, as a Maz and high figure of the Temple, worthy of interest?

I immediately regretted this disrespectful thought and tried hard to forget it. Unsuccessfully.

By following my curiosity, I disturbed Peace. But in turning a blind eye to my doubts, I insulted Knowledge and Tolerance.

Why had Maz Achem been silenced?

I decided to find out.