The Other Girl (3 page)

Authors: Pam Jenoff

“And then what?” Hannah asked. Maria bit her lip as she tried to summon the answers she did not have.

“We'll think of something,” Janusz interjected, calling down softly from above.

We.

They were suddenly a unit. Maria felt stronger than she had in months. But she still did not have answers.

“Thank you.” Hannah's voice was full of appreciation.

“You rest. It will be all right.” She was making assurances that were not hers to give. Suddenly she had an idea. “If your father was gone, what then? Would you go back?”

Hannah did not answer, but Maria could see that she was unable to fathom a world where home was safe. Finally the girl shook her head.

“Perhaps in the morning you'll feel differently,” Maria said.

“No.” The resolute look in Hannah's eyes suggested that nothing would change in one day or one year. Anyway, Maria reflected, the question of Hannah's father being gone was a moot one. “Maybe things would be different if I was strong like you,” the girl added wistfully. Maria was surprisedâshe had not thought of herself in that way before. She opened her mouth to tell Hannah that she was the brave one, running away on her own. But the girl had closed her eyes and was breathing evenly.

Watching Hannah sleep, her face innocent and soft, Maria's anguish deepened. Who could harm such a girl? Her hand rested protectively on her stomach. She had already despaired of bringing a child into this world of fighting and hardship. But how could she ever hope to protect her baby from such things?

Maria rose, climbed the ladder and joined Janusz in the cottage. “You'll keep an eye on her?” she asked him in a low voice. He nodded. She wanted to ask Janusz if he could use his contacts to help the girl, but it seemed unwise to push. “I'm not sure what to do with her,” she offered instead.

“We'll figure it out in the morning. You should go now before you are missed.”

Maria went to the front door, assaulted by the cold as she opened it. Buttoning her coat, she turned back to Janusz. There was something in the shape of his eyes beneath the bushy brows that reminded her of the face she saw when she looked in the mirror. She pushed aside the thought. “Good night.”

Maria recrossed the field, feeling strangely lonely without the girl beside her. The images of her mother and Janusz at the cabin seeped into her mind once more. There had been a last letter, shorter and sadder than the others.

Little Bird

,

I'm setting you free.

“Little Bird” must have been his nickname for Mama, dainty and petite. Mama always seemed so sweet and loyal, simple. It was hard to picture her as the object of passion described in the letters, even less so now that Maria knew her portly, scruff-bearded cousin was the author. She was suddenly angry at her mother's betrayal. But who was she to judge? Perhaps Mama had been bereft over Marek's death, and Papa had not been there for her in the way she had needed. Maria hadn't been old enough to know. Once she had thought her home life idyllic. Now her father had proven to be a traitor, her mother unfaithful. How could this sleepy little villageâand the house where she had spent nearly her whole lifeâharbor so many secrets?

As she reached the edge of the village, she turned back to look at Janusz's farm, the windows now dark. Her thoughts turned to Hannah. The child would not return to her home and Maria could not force her. If Maria took her to the police, they would only turn her in to the Germans. Could she take her to an orphanage in the city? Perhaps Piotr might be persuaded to let her keep the child and raise her as their own. Her in-laws, though, would never agree.

She started walking again, this time east, taking a different path skirting the edge of the village. It was not until she neared her parents' house that she realized where her feet were taking her. Without stopping, she walked determinedly to the door and knocked.

A second later the door swung open and her father's large frame filled the doorway, silhouetted against the light within. In the corner by the fireplace, she could just glimpse his violin case, and she wondered when he had last played. The familiar smell of her mother's cooking sent her reeling back to childhood. For a second she wanted to step inside and pretend that their estangement and her leavinghad never happened.

Her father's eyes widened. “Marishu,” he said, using his pet name for her and forgetting the acrimony. Then his brow furrowed. “What's wrong? Have they been unkind to you?” Something in Maria softened. For all of their differences, he still cared about her. Things might be mended between them if only she could accept what he had done.

But too much had happened for thatâhe was not the father she had once idolized. Had he found Hannah, he surely would have turned her in, even though she was a girl just like Maria herself had once been. “No,” she replied quickly, her tone cold and brisk. “Everything is fine. I only wanted to tell you that I've heard of a Jew over in Lipnik who is hoarding. He's called Stein.” Doubt flashed through her. She had come here on impulse, trying to find a way to save Hannah from her cruel father. But what if they punished not just the man, but his wife as well? This way was such a crude way to exact justice

“How did you find this out?” he demanded. “And why are you telling me?”

“I just am.” She considered telling him that he would soon be a grandfather, then decided against it. “How's Mama?”

“Fine. She's sleeping.” He did not offer to wake her. She waited for the invitation inside that did not come.

“I have to get home,” she said finally. This had been her home once, but it wasn't anymore. “Goodbye, Papa,” she added because there was nothing else left to say. She turned and walked away, feeling him watch her as she crossed the field to ensure she made it safely. That he still cared was something.

Maria hurried to Piotr's house, her footsteps lighter. In the morning she would tell Hannah that she had made things safeâthat her father would not be able to hurt her anymore and she could go home. The house was dark and Maria slipped into bed quietly. She lay awake in the darkness, imagining how this might go. She would have to find a place for Hannah, temporarily, until her father was gone. Perhaps she could ask Father Dominik to help find a family to take her in. If not, Piotr's family would have to let her stay. There was enough room. Hannah could work, be useful. It would be good to have a friend, Maria reflected as her eyes grew heavy. Someone she could talk to in this cold, quiet house.

Maria slept roughly over the next few hours, awakening well before dawn. She dressed hurriedly and set out for Janusz's cottage. When she arrived, she paused, not wanting to wake him. The key was hidden beneath the windowsill, just as it had been when she was a girl. She quietly pushed the door open and climbed the ladder down into the cellar. Then she let out a soft gasp. Hannah was gone.

Had the police come? No, the blankets were folded, signaling that the girl's departure had been orderly. She ran her hand over the straw, as if doing so might offer a clue to where the girl had gone.

She turned as she heard Janusz climbing down behind her with effort. “She's gone,” Maria said, her voice flat despite her shock.

“Yes.” He did not sound surprised. “I offered to put her in touch with people who could help if only she would wait. But she refused.” Because even after meeting Maria and Janusz, she couldn't trust anyone but herself, Maria knew. “I couldn't stop her,” he added.

Maria started up the ladder. “Perhaps we can catch her.”

But Janusz took her arm, stilling her. “She's been gone an hour. And more importantly, she doesn't want us to.”

Resigned, Maria followed Janusz back up the ladder. Her eyes traveled to his uniform, which always had hung proudly by the door. The gold eagle pin, which had been affixed to the lapel, was missing. She touched the collar. “Did she take it?”

“I gave it to her.”

“Why?”

“I gave her what she needed to get away.” And set her freeâthe way he surely had Mama years ago. Maria wished that she might have given the girl something, too, but she had no money or valuable possessions of her own.

Maria walked to the door of the cottage and opened it. She saw footprints in the snow that she had not noticed earlier, smaller than her own, moving south away from the house. Hannah had kept going, as far as she could from home.

Maria drew her coat more tightly around her, then turned back. “Thank you.” She considered lingering to ask Janusz more about the past and what her mother had meant to him. But she was not sure he would tell herâor whether she really wanted to know.

“Give your mother my best,” he said, unable to restrain himself. “If you see her.”

“I shall,” she lied, knowing she would not return again to her parents' house.

“And come visit again sometime.” He seemed smaller then, an old man all alone with his memories.

She reached up and kissed his coarse cheek and he reddened at the unfamiliar affection. As Maria reached the edge of the field, she gazed up into the forest. She thought of Piotr with unexpected longing. It would be good if he were here and she could tell him what had happened. Perhaps Mama was right: love

did

grow.

She took one last look in the direction Hannah had gone, surprised by the sadness that overcame her. The child had been a dangerous burden, and her leaving freed Maria of a responsibility she had not asked for and had never wanted in the first place. Maria could fade into the background once more. But while Hannah was here, even for that brief time, Maria had felt stronger and less lonely. She pressed forward, reshaped somehow by the experience.

Of course, the girl might do just fine. She was strong despite her size, and she undoubtedly had the will. In these uncertain times, she had as much a chance as anyone. The eagle pin Janusz had given her was valuable and could be bartered for the goodwill of the Germans or even for money or food. There was hope that she might survive somehow.

Maria looked toward the forest with a touch of envy. Though Hannah was in certain peril, she was free in a way that Maria would never be. “Godspeed,” she whispered into the wind and then started back toward home.

* * * * *

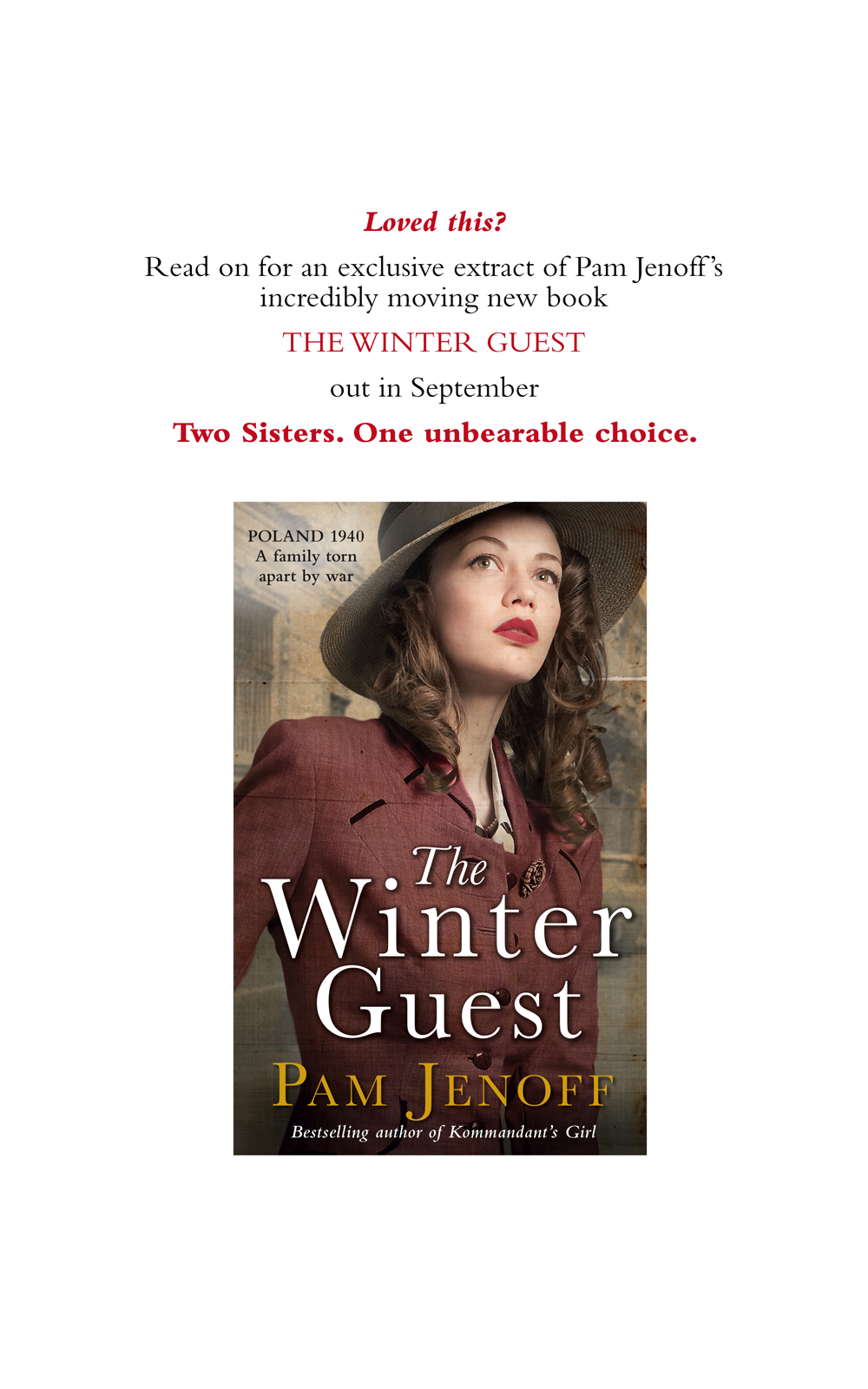

Pam Jenoff is the author of several novels, including the international bestseller

Kommandant's Girl

, which earned her a Sophie Brody Medal and Quill Award nomination. Along with a bachelor's degree in international affairs from George Washington University and a master's degree in history from Cambridge, Pam also received her Juris Doctor from the University of Pennsylvania. She has previously served as a foreign service officer for the US State Department in Europe, as the special assistant to the secretary of the army at the Pentagon and as a practicing attorney. Pam lives with her husband and three children near Philadelphia, where, in addition to writing, she teaches law school.

Prologue

New York, 2013

“They're coming around again,” Cookie says in a hushed voice. “Knocking on doors and asking questions.” I do not answer, but nod as a tightness forms in my throat.

I settle into the worn floral chair and tilt my head back, studying the stucco ceiling, the plaster whipped into waves and points like a frothy meringue. Whoever said, “There's no place like home” has obviously never been to the Westchester Senior Center. One hundred and forty cookie-cutter units over ten floors, each a six hundred and twenty square foot L-shape, interlocking like an enormous dill-scented honeycomb.

Despite my issue with the sameness, it isn't an awful place to live. The food is fresh, if a little bland, with plenty of the fruit and vegetables I still do not take for granted, even after so many years. Outside there's a courtyard with a fountain and walking paths along plush green lawns. And the staff, perhaps better paid than others who perform this type of dirty and patience-trying work, are not unkind.

Like the white-haired black woman who has just finished mopping the kitchen floor and is now rinsing her bucket in the bathtub. “Thank you, Cookie,” I say from my seat by the window as she turns off the water and wipes the tub dry. She should be in a place like this with someone caring for her, instead of cleaning for me.

Coming closer, Cookie points to my sturdy brown shoes by the bed. “Walking today?”

“Yes, I am.”

Cookie's eyes flicker out the window to the gray November sky, darkening with the almost-promise of a storm. I walk almost every day down to the very edge of the path until one of the aides comes to coax me back. As I stroll beneath the timeless canopy of clouds, the noises of the highway and the planes overhead fade. I am no longer shuffling and bent, but a young woman striding upward through the woods, surrounded by those who once walked with me.

And I keep a set of shoes by the bed all of the time, even when snow or rain forces me to stay indoors. Some habits die hard. “How's Luis?” I ask, shifting topics.

At the mention of her twelve-year-old grandson, Cookie's eyes widen. Most of the residents do not bother to learn the names of the ever-changing staff, much less their families'. She smiles with pride. As she raises a hand to her breast, the bracelet around her wrist jangles like ancient bones. “He made honor roll again. I'm about to go get him, actually, if you don't need anything else...”

When she has gone, I look around the apartment at the bland white walls, the venetian blinds a shade yellower with age. Not bad, but not home. Home was a brownstone in Park Slope, bought before the neighborhood had grown trendy. It had interesting cracks in the ceiling, and walls so close I could touch both sides of our bedroom if I stretched my arms straight out. But there had been stairs, narrow and steep, and when my old-lady hips could no longer manage the climb, I knew it was time to go. Kari and Scott invited me to move into their Chappaqua house; they certainly have the room. But I refusedâeven a place like this is better than being a burden.

I look across the parkway at a strip mall now past its prime and half-vacant, wondering how to spend the day. The rest of my life rushed by in an instant, but time stretches here, demanding to be filled. There are activities, if one is inclined, knitting and Yiddish and aqua fitness and day trips to see shows. But I prefer to keep my own company. Even back then, I never minded the silence.

One drop, then another, comes from the kitchen faucet that Cookie did not manage to shut. I stand with effort, grimacing at the dull pain that shoots through my thigh, the wound that has never quite healed properly over more than a half century. It hurts more intensely now that the days have grown shorter and chilled.

Outside a siren wails and grows closer, coming for someone here. I cringe. Now, it is not death I fear; each of us will get there soon enough. But the sound takes me back to earlier times, when sirens meant only danger and saving ourselves mattered.

As I start across the room, I catch a glimpse of my reflection in the mirror. My hair has migrated to that short curly style all women my age seem to wear, a fuzzy white football helmet. Ruth would have resisted, I'm sure, keeping hers long and flowing. I smile at the thought. Beauty was always her thing. It was never mine, and certainly not now, though I'm comfortable in my skin in a way that I lacked in my younger years, as if released from an expectation I could never meet. I did feel beautiful once. My eyes travel to the lone photograph on the windowsill of a young man in a crisp army uniform, his dark hair short and expression earnest. It is the only picture I have from that time. But the faces of the others are as fresh in my mind, as though I had seen them yesterday.

A knock at the door jars me from my thoughts. The staff has keys but they do not just walk in, an attempt to maintain the deteriorating charade of autonomy. I'm not expecting anyone, though, and it is too early for lunch. Perhaps Cookie forgot something.

I make my way to the door and look through the peephole, another habit that has never left me. Outside stand a young woman and a uniformed policeman. My stomach tightens. Once the police only meant trouble. But they cannot hurt me here. Do they mean to bring me bad news?

I open the door a few inches. “Yes?”

“Mrs. Nowak?” the policeman asks.

The name slaps me across the cheek like a cold cloth. “No,” I blurt.

“Your maiden name was Nowak, wasn't it?” the woman presses gently. I try to place how old she might be. Her low, dishwater ponytail is girlish, but there are faint lines at the corners of her eyes, suggesting years behind her. There is a kind of guardedness that I recognize from myself, a haunted look that says she has known grief.

“Yes,” I say finally. There is no reason to hide who I am anymore, nothing that anyone can take from me.

“And you're from a village in southern Poland called...Biekowice?”

“Biekowice,” I repeat, reflexively correcting her pronunciation so one can hear the short

e

at the end. The word is as familiar as my own name, though I have not uttered it in decades.

I study the woman's nondescript navy pantsuit, trying to discern what she might do for a living, why she is asking me about a village half a world away that few people ever heard of in the first place. But no one dresses like what they are anymore, the doctors eschewing white coats, other professionals shedding their suits for something called “business casual.” Is she a writer perhaps, or one of the filmmakers Cookie referenced? Documentary crews and journalists are not an uncommon site in the lobby and hallways. They come for the stories, picking through our memories like rats through the rubble, trying to find a few morsels in the refuse before the rain washes it all away.

No one has ever come to see me, though, and I have never minded or volunteered. They simply do not know who I am. Mine is not the story of the ghettos and the camps, but of a small village in the hills, a chapel in the darkness of the night. I should write it down, I suppose. The younger ones do not remember, and when I am gone there will be no one else. The history and those who lived it will disappear with the wind. But I cannot. It is not that the memories are too painfulâI live them over and over each night, a perennial film in my mind. But I cannot find the words to do justice to the people that lived, and the things that had transpired among us.

No, the filmmakers do not come for meâand they do not bring police escorts.

The woman clears her throat. “So Biekowiceâyou know of it?”

Every step and path, I want to say. “Yes. Why?” I summon up the courage to ask, half suspecting as I do so that I might not want to know the answer. My accent, buried years ago, seems to have suddenly returned.

“Bones,” the policeman interjects.

“I'm sorry...” Though I am uncertain what he means, I grasp the door frame, suddenly light-headed.

The woman shoots the policeman a look, as though she wishes he had not spoken. Then, acknowledging it is too late to turn back, she nods. “Some human bones have been found at a development site near Biekowice,” she says. “And we think you might know something about them.”