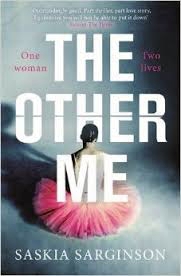

The Other Me

Authors: Saskia Sarginson

‘A captivating blend of mystery, thriller and family drama’

Sun

‘Atmospheric, readable, beautifully evoked’

Sunday Mirror

‘Intense… dark’

Daily Mail

‘Convincing and compelling… building tension that resonates even after the novel ends’

Stylist

‘Thumpingly good’

Good Housekeeping

‘Gripping, original and heartbreaking’

Gransnet

‘Gripping’

Marie Claire

‘Clever, and full of suspense’ Richard Madeley

‘Stunning in its insight and beautifully written’ Judy Finnigan

‘A perfect R & J read. Highly compulsive’

Bookseller

‘Strong characters, intense atmosphere and intricate narrative’

Woman & Home

‘An excellent debut, and you are sure to have a hard time putting it down’

Candis

‘This book got its hooks into us and wouldn’t let go. Hypnotic, with real emotional punch’

Star

‘This debut reveals a stunning writer with deep insight into people. A beautifully crafted and compelling story that won’t disappoint’

NZ Women’s Weekly

‘Timeless and riveting’

Romantic Times

‘The haunting tale is skilfully infused with trauma and tragedy – and sinister suspense. [A] stirring debut’

Independent.ie

The Twins

Without You

The Other Me

COPYRIGHT

Published by Piatkus

978-0-3494-0339-7

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2015 by Saskia Sarginson

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

PIATKUS

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

The Other Me

Table of Contents

For Alex M

Our nightmare of total transparency conflicts with our dream of being entirely known.

Thomas Nagel

I have no experience of killing anything. I take extra-long strides or sudden little hops to avoid stepping on insects that cross my path. When there’s a wasp in the house, I cup it inside a mug so I can set it free out of the window. Feathered remains left in our garden after a cat has slunk away make me cry. I’m practically Buddhist. So how am I going to kill him?

Murder used to be a word that belonged to cloak-and-dagger plays or police dramas on TV. It had nothing to do with me. Not until he began to talk last night, telling me things I could never have guessed, asking me to do something terrible.

It started to snow this afternoon. The first flakes falling in nervous flurries from a gunmetal sky. Now, looking out into the evening, there is nothing but snow swirling towards me, white on white. Ice crystals billow out of darkness, twisting, spinning, casting a blinding spell. My breath makes a warm mist against the chill of the window. I close my eyes, leaning my forehead on the glass, and think about how I could stop his heart.

Perhaps suffocation would be kind? Slipping into his room at night, to hold a pillow over his face. Only I think that even when sleeping, the natural impulse is to fight for life, and I imagine his legs jerking and kicking out, the awful wrestle with the thrash and twist of his body.

There is a handgun in the top left-hand drawer of the portmanteau. I found the key once and opened it. Stared at the pistol, too scared to pick it up. My eyes followed the heavy lines of the barrel and worn grip. This time I’d feel the weight of it in my palm, slotting bullets into the snug nest of the cylinder. But I’ve seen the films, I know what happens when a bullet tears through a skull: blood, an explosion of it, and scraps of shattered bone, the gloopy insides coming out. Anyway, I’ve never fired a gun. I could end up maiming him instead.

I can’t believe that I’m even considering this.

The garden is covered in a thick, dampening carpet of snow. Neat flowerbeds have become small white graves. The naked apple tree holds up silvery branches. The hushed world is transformed. Beyond our garden fence, streetlights gleam, catching snowflakes in illuminated fans. A car rolls past slowly, wheels crunching. The street is oddly deserted. But in the distance the city hums, vibrations pulling at the atmosphere – even the snow can’t silence it – a constant reminder that a huge metropolis exists, the centre of everything, and here I am creeping on the fringes, still tethered to the life I thought I’d left behind. I have always hated living in the suburbs, neither in nor out, neither one thing nor another.

It has to be pills. It’s the safest way, surely? I’ll have to acquire them in furtive visits to different chemists. No. That won’t work, because I don’t have weeks, not even days. It has to be now. I need another kind of drug, something immediate and powerful enough to let his dreams drag him under, so that he drowns silently, invisibly, within his own body. I think of his lungs, his heart, his muscles, the secret core of him, unclenching, letting go at last.

I’ve felt for a long time now that we inherit guilt – it passes forwards like crinkly hair, a squint, or blood that won’t clot. We don’t get a choice.

Will my guilt die too when I kill him?

1986, London

All through the long drag of summer my stomach knotted and unravelled when I thought about what was going to happen in September. I’d circled the date on the calendar in red felt-tip with pink stars shooting out over the surrounding days. Inside the scrawl of rose and scarlet it said:

Tuesday 3rd. Klaudia starts at Kelwood High School.

I’ve often walked past the big brick building on Mercers Road, pausing to glance at crowds of pupils in green and grey, watching them spill out of the gates, arm in arm, chatting and laughing. I used to wonder what they were saying, what it was that made them laugh. Now I’ll find out, because it’s going to be me in that uniform, skipping down the steps, my elbow linked with a friend’s.

I’ve been taught at home. Mum and I at the kitchen table with a pile of exercise books, working our way through the syllabus, learning things by rote so that I could repeat them to my father when he came home from work.

I’m worried that not going to school has made me different. Perhaps it’s even more strange that I’m an only child, or that my parents are as old as grandparents. I don’t know, because I haven’t learnt any of the rules. Mum says I just have to be myself. I’m sure it’s more complicated than that.

There’s only the three of us at home: me, Mum and Dad. Well, four of us, if you count Jesus. Nothing ever actually happens at our house. Nothing ever changes. Reflections flicker inside surfaces and windows sparkle; the three cushions propped on the velveteen sofa don’t move out of position, and the pictures on the walls are never wonky, especially the framed tapestry in the living room that reads,

All may be saved to the utter most.

My father checks its alignment every morning, squinting one eye and standing back to read the needlepoint lettering as if he doesn’t know it, and a hundred other lines of scripture, off by heart.

Wooden ornaments jostle for space on the mantelpiece and dresser: the twelve apostles and Jesus in different poses, hand raised or holding a basket of fish, all staring out with blind eyes, frozen in place, as if the witch from Narnia has been on the rampage. Even these don’t have a speck of dust on them. Each one is lifted and re-positioned after a thorough polish. Hunting dirt is something my mother does, feather duster in hand, the vacuum cleaner like a faithful pet, rolling from room to room with its long nose snuffling into corners.

I wish we could have a real pet. ‘We don’t live on a farm, Klaudia,’ my father told me when I asked, ‘and it would add to your mother’s burdens.’ My mother sighed, ‘It’s a shame, cariad, but a cat would kill the birds.’ Mum feeds the robins, sparrows and thrushes that live in our garden with bits of bacon fat and the broken skulls of coconuts. My father made a bird table for her and fixed it on a branch of the apple tree. He likes to make things from wood. We’re running out of places to put the ornaments, and there are a lot of characters in the Bible still to go. He has a shed in the garden where he keeps his tools and does his carving.

That’s the other thing about starting school that worries me. My father. Otto Meyer. He works there. That’s embarrassing.

He

is embarrassing. He’s like Goliath, always too big for any room. And of course there’s his heavy German accent. How can he still talk like that when he’s lived in England for years and years? But maybe nobody will know or care that he’s my dad. I’ll make friends. Kids my own age. I want to take a look inside their homes and see how they live and what they eat and what they watch on TV. There is a whole world outside these pebble-dashed walls, beyond our straight suburban street, the Guptas’ local store, the Methodist chapel and the Texaco garage blinking its orange lights on the main road.

The teacher, Mrs Jones, is writing on the blackboard with chalk. I bend low over the desk and try to keep up with copying. I can feel the good-luck postcard that Mum gave me this morning crumpled in my pocket. Its edges press against my skin through the silky lining.

Most of the kids already seem to know each other. Lots of them must have gone to the same primary school. That hadn’t occurred to me. I thought we’d all be new. After I’d found a spare desk, I perched on the edge of my chair wondering how to join in with one of the conversations. A girl stopped by my desk.

‘Hello. I’m Lesley.’ She put her head on one side. ‘Have you just moved here?’

‘Oh, no,’ I gabbled, ‘I’ve lived here for my whole life. Just around the corner.’

She’d curled her lip. ‘Well, how come I’ve never seen you?’

‘I didn’t go to school. My mum taught me. At home,’ I said quickly.

The way she looked at me – it was as if I was a purple-spotted lemur in the zoo. I shouldn’t have said anything. I knew it was wrong.