The Oxford History of World Cinema (35 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

Count from Pappenheims. In France René Clair brought the comedy style of the French

stage vaudeville to the screen with The Italian Straw Hat (

Un chapeau de paille d'Italie,

1927) and

Les Deux Timides

( 1928). But screen comedy was distinctly an American art

form.

It was to remain so, although the golden age of silence was abruptly extinguished with the

coming of sound. The causes were manifold. Some comedians were disoriented by the

fact of sound itself ( Raymond Griffith was an extreme case, having a severe throat defect

which restricted his power of speech). The new techniques -- the microphones and the

cameras enclosed in sound-proof booths -suddenly restricted the freedom of film-makers.

More important the escalating costs and profits of film-making led to much closer

production supervision, which generally proved inimical to the independence which had

been vital to the working methods of the best comedians. Rare ones, like Chaplin and

Lloyd, were able to win themselves freedom of operation for a few more years, but

others, including Keaton and Langdon, found themselves employees of huge film

factories which had no place or concern for individualists. After 1929 Keaton never

directed another film, and Langdon vanished into obscurity. A new art had been born, had

flowered, and died in little more than a quarter of a century.

Bibliography

Kerr, Walter ( 1975),

The Silent Clowns

.

Lahue, Kalton C. ( 1966),

World of Laughter

.

------ ( 1967),

Kops and Custard

.

McCaffrey, Donald W. ( 1968),

Four Great Comedians

.

Montgomery, John ( 1954),

Comedy Films: 1894-1954

.

Robinson, David ( 1969),

The Great Funnies: A History of Film Comedy

.

Buster Keaton (1895-1966)

Of all the great silent comedians, Buster Keaton is the one who suffered the worst eclipse

with the coming of sound but whose reputation has recovered the best. He was born

Joseph Francis Keaton, in Piqua, Kansas, where his parents were appearing in a medicine

show. Nicknamed Buster by fellow artist Harry Houdini, he joined his parents' act while

still a baby. By the age of 5 he was already an accomplished acrobat and was soon billed

as star of the show. In 1917 the family act broke up. Buster went to work with Roscoe

(Fatty) Arbuckle at his Comique film studios in New York and then followed Arbuckle

and producer Joe Shenck to California at the end of the year. He worked with Arbuckle

for a couple of years, learning filmcraft with the same dedication as he had given to

stagecraft, but struck out on his own, with Schenck's backing, in 1921. Between then and

1928, with Schenck as his constant mentor and producer (and also brother-in-law, since

each had married one of the Talmadge sisters), he starred in some twenty shorts and a

dozen features, almost all of which he directed himself and on which he enjoyed total

creative freedom. To this period belong such classics as The Navigator ( 1924), The

General ( 1926), and Steamboat Bill, Jr. ( 1928). The coming of sound brought an even

more abrupt end to his career than to those of many other artists of the silent period.

Losing Schenck's patronage, he joined MGM as a salaried contract artist with no creative

control. His marriage to Natalie Talmadge broke up definitively in 1932. In the last

twenty-five years of his life, which was plagued with personal problems, he struggled to

keeep his career alive. Throughout the early sound years and into the 1940s he appeared

in numerous second-rate films which gave little scope for his unique silent persona. But

he was largely forgotten by the public until invited to play opposite Chaplin in a brilliant

cameo in the latter's Limelight ( 1951). His career began to pick up and his financial and

personal difficulties lessened. His last film appearance was in Richard Lester's A Funny

Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum in 1965.

Keaton was above all a consummate professional. A brilliant and extremely courageous

acrobat, he devised the most elaborate gags and performed them with extraordinary

aplomb. Only rarely did he have recourse to tricks and special effects, and when he did

the effects often constitute gags of their own, almost as ingenious as his own

performances. Sometimes the effects are transparent, as in the transitions between reality

and fantasy in Sherlock Jr. ( 1924); sometimes they are concealed, as with the mechanism

that controls the mysterious behaviour of the doors in The Navigator. In Our Hospitality

( 1923), where the rescue of the heroine intercuts shots which really are on the raging

rapids with studio mock-ups, the basic effect remains one of realism. The sense of being

in a real world, full of real, if recalcitrant, objects, provides an essential context for those

moments in Keaton films in which objects -- as in the much imitated gag of the sinking

lifebelt -- do not behave in realistic ways.

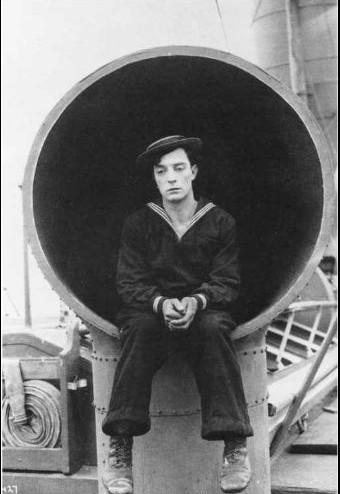

Buster Keaton in The Navigator ( 1924)

Keaton's mastery of timing -- the natural comedian's stock-in trade -- was extraordinary.

From very early on, however, he extended it from the field of acting performance into that

of extended mise-en-scéne. He developed running gags and constructed comic scenes

which lasted for several minutes and delpoyed extensive resources, often centred around

moving objects such as trains or motor-bikes. Control of the architecture of these scenes

was as important as the comic business carried by his performance. When the house in

One Week ( 1920) is demolished, not by the train the audience expects to destory it, but

by another one steaming in from a different angle, and the hero is left bemused and

forlorn among the wreckage, it is hard to say whether it is Keaton he director or Buster

the performer who is most to be admired. The saddest feature of his later films, from

Spite

Marriage

( 1929) onwards, is not the loss of his performing talent but the fact that

he could no longer construct entire films in which to develop it.But Keaton's gags would

be mere pyrotechnics were it not for the personality of Buster himself. A slight figure,

with a seemingly impassive face, generally equipped with a straw hat placed (to borrow T.

S. Eliot's phrase about Cavafy) at a slight angle to the universe, Buster was the perennial

innocent plunged into ridiculous and impossible situations and emerging unscathed throuh

a mixture of obstinacy and unexpected resource. Unlike Chaplin or Lloyd, the Buster

persona makes no appeal to the audience. He is a blank sheet, on whom testing

circumstances and awakening sexual desire gradually impose a character. At the outset he

Buster character tends to be a dreamer or a fantasist, blissfully unaware of the gap

between reality and fantasy or the obstacles that might stand in the path of realizing his

desire. Faced with recalcitrant objects or hostile fellow-beings, he remains unfazed,

tackling each obstacle with grim determination and expedients of greater and greater

daring and extremity. By the end when he (usually) wins the girl, he has become wiser to

the world, but his innocence remains.In September 1965, Keaton, now nearly 70, made a

personal appearance at the Venice film Festival, where he was tumultuously applauded.

He died of cancer a few months later.

GEOFFREY NOWELL-SMITH

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

Short films

The Butcher

Boy (with Roscoe Arbuckle) ( 1917); Back Stage (with Roscoe Arbuckle) ( 1919); One

Week ( 1920); Neighbors ( 1920); The Goat ( 1921); The Playhouse ( 1921); The Paleface

( 1921); Cops ( 1922); The Frozen North ( 1922)

Keaton -- Schenck features

Three Ages (

1923); Our Hospitality ( 1923); Sherlock Jr. ( 1924); The Navigator ( 1924); Seven

Chances ( 1924); Go West ( 1925); Battling Butler ( 1926); The General ( 1926); College

( 1927); Steamboat Bill, Jr. ( 1928)

MGM productions (silent period)

The Cameraman

( 1928); Spite Marriage ( 1929)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blesh, Rudi ( 1967),

Keaton

.

Keaton, Buster ( 1967),

My Wonderful World of Slapstick

.

Robinson, David ( 1969),

Buster Keaton

.

Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977)

At the age of 24, after only a few days in pictures and a single film appearance, Charles

Chaplin created the comic character that was to bring him world fame, and which even

today remains the most universally recognized fictional representation of human kind --

an icon both of comedy and the movies themselves.

Chaplin's little Tramp appears to have been a spontaneous, unpremeditated creation. On

or about 5 January 1914, deciding that he needed a new comic persona for his next one-

reel film, he went into the wardrobe shack at the Keystone Studios, and emerged in the

costume, make-up and character more or less as we still know it. He had invented many

stage characters before, and he would continue to experiment with others on the screen;

but no figure that he or any other comedian created would ever be so potent.

Chaplin's first ten years had witnessed more tribulation than most human beings ever

encounter in long lifetimes. His father, a moderately successful singer on the London

music halls -- apparently exasperated by his wife's infidelities -- abandoned his family,

and succumbed to alcoholism and early death. His mother, a less successful music hall

artist, intermittently struggled to maintain Charles and his half-brother Sydney. As her

health and mind broke down -- she was eventually permanently confined to mental

hospitals -- the children spent extended periods in public institutions. By his tenth year

Charles Chaplin was familiar with poverty, hunger, madness, drunkenness, the cruelty of

the poor London streets and the cold impersonality of public institutions. Chaplin

survived, developing his selfreliance.

At ten years old he went to work first in a clog-dance act and then in comic roles; and by

the time he jointed Fred Karno's Speechless Comedians in 1908 he was well versed in

every kind of stage craft.

Karno was a London impresario who had built his own comedy industry, maintaining

several companies, with a 'fun factory' to develop and rehearse sketches, to train

performers, and to prepare scenery and properties. An inspired judge of comedy, Karno

groomed several generations of talented comedians, including Stan Laurel and Chaplin

himself. In length, form and knockabout mime, Karno's sketches closely anticipated the

classic one-reel comedy of the early cinema.

While touring he United States as the star of a Karno sketch company, Chaplin was

offered a contract by the Keystone film company. Mack Sennett, its chief, was very much

the Hollywood equivalent of Karno -- an impresario with a special gift for broad comedy.

After a tentative first film, Making a Living, Chaplin devised his definitive role (the

costume was first seen in 1914 in Kid Auto Races at Venice) and embarked on a series of

one-reel films that within months made him a household name. The potency of the Tramp

was that in creating this character, Chaplin used all the experience of humanity he had

absorbed in his first ten years, and transformed it into the comic art he had so completely

mastered in the apprenticeship of the years that had followed.

Dissatisfied with the breakneck Keystone pace that give him no chance to develop his

subtler comedy style, Chaplin quickly persuaded Sennett to let him direct, and after June

1914 was always to be his own director. He left Sennett at the end of the year's contract,

moving from company to company in search of greater rewards and also, more important

in his view, greater creative independence.