The Oxford History of World Cinema (72 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

So, despite this general shift towards westernized cinematic styles, traditional Japanese

forms were not totally abandoned. Indeed in 1922 Eizo Tanaka made the masterpiece

Kyoya erimise ('Kyoya, the collar shop') employing oyama. Unlike the contemporary

directors at Shochiku, Tanaka did not simply follow American cinematic trends. This was

a film about an old collar shop, Kyoya, in which the downfall of one family, and, by

implication, of old Japan, is described through the passing of the four seasons. The

distinction of the seasons in this film corresponds to seasonal words in haiku, traditional

Japanese poetry, which, added to the poetic background and atmosphere of downtown

Tokyo, made this the most refined form of Japanese traditional art achieved by the cinema

to date. As one of the last Nikkatsu films that employed oyama, Kyoya erimise was the

final swan-song of archaism in the vanishing old style of Japanese cinema. Without

demolishing the concepts of conservative film, Nikkatsu was able to preserve the pure

Japanese plastic beauty in this masterpiece. For the film, Tanaka constructed the Kyoya

shop in its entirety in the Mukojima studio. The partition walls could be removed

according to the camera position, and for natural representation of actors' movement from

room to room and from the verandah to the garden.

After this, Nikkatsu was to make a series of high-quality films, before the Great Kanto

Earthquake of September 1923. Tanaka made Dokuro no mai ('Dance of the skull', 1923),

using actors and actresses who belonged to the Association of Stage Players. It was a

portrayal of the asceticism of a Buddhist priest and, at eleven reels, was highly ambitious.

Critics compared it to classic foreign works, in particular Stroheim's Foolish Wives

( 1922). Japanese films were finally being received on the same level as foreign,

especially American, films.

Together with Tanaka, Kensaku Suzuki was the first auteur in the history of Japanese

cinema. In addition to these two, younger directors emerged in this period, like Osamu

Wakayama and, youngest of all, Kenji Mizoguchi, Tanaka's protégé and assistant on

Kyoya Erimise. Some of the most important achievements in Japanese film are found in

the works of Suzuki. In a short period of activity, he realized a film form akin to the

European avant-garde, and anticipated a wholly new trend of film-making that would

arise suddenly in the aftermath of the Earthquake. The extremely pessimistic style and

content of his films were feverishly applauded by the young audience of the time. Tabi no

onna geinin ('The itinerant female artiste', 1923) portrays the parallel lives of two

desperate souls, a man and a woman who only meet by chance in the final scene to part

again and go on their gloomy ways. In the Stroheimian Aiyoku no nayami (Agony of

lust', 1923) an old man is tragically besotted with a younger woman. The bleakest realism

came in Ningen-ku ('Anguish of a human being', 1923), in which Suzuki rejected

conventional narrativity, and demonstrated his ideology of pessimism in a new form. The

first reel of this four-reel film shows the fragmented existences of various assorted low-

life characters: a starved old man, a group of tramps, bad boys, and prostitutes. The lives

of these poor and ill-fated people is paralleled by the glittering images of an aristocratic

ball. Following this, a poor man sneaks into the home of a rich man and witnesses the

master of the house, who is bankrupt, committing suicide after killing his wife. The film

depicts events from about 10 p.m. to 2 a.m., so that all the scenes are shot at night, with a

grim mise-en-scène of rainy streets, gas lamps, flowing muddy water, and dilapidated

buildings. Suzuki, insisting on extreme realism, made the actor who played the 'shadowy

old man' fast for three days. Other innovations in Ningen-ku include frequent close-ups,

dialogue intertitles, and, notably, rapid editing that was not to be the norm in Japan until

the late 1920s.

By 1923 Japanese cinema had virtually demolished the long-standing traditional form, on

the one hand by assimilating American cinema, and on the other through the inspiration of

avant-garde film forms such as German Expressionism and French Impressionism.

Nevertheless, Japanese cinema had not only assimilated and imitated. For example, the

point-of-view shot was extremely scarce in Japanese cinema even in the mid-1920s. This

resulted from the fact that Japanese cinema depended on the force of narrative illusionism

constituted by the voice of the benshi, and from the long-standing tradition of the distance

kept between the object and the lens of the camera. The archaic form of Japanese art and

culture still exerted influence on Japanese cinema beyond the early period.

Bibliography

Anderson, Joseph L., and Richie, Donald ( 1982), The Japanese Film: Art and Industry.

Burch, Noël ( 1979), To the Distant Observer.

Nolletti, Arthur, Jr., and Desser, David (eds.) ( 1992), Reframing Japanese Cinema:

Authorship, Genre and History.

Sato, Tadao, et al. (eds.) ( 1986), Koza Nihon Eiga, i and ii.

Tanaka, Junichiro ( 1975), Nihon Eiga Hattatsu Shi, i and ii.

Daisuke Ito (1898-1981)

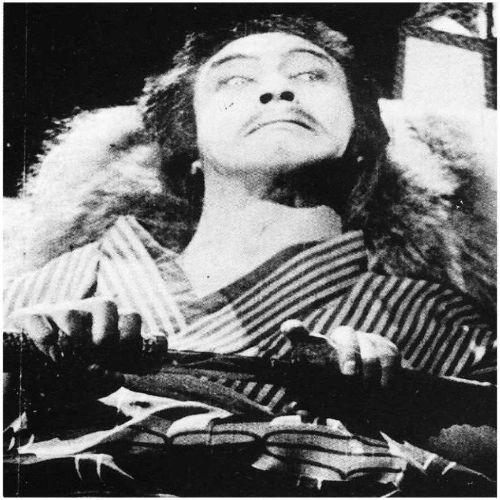

A short from Daisuke Ito's recently redisovered masterpiece Chuji tabi nikki (' A diary of

Chuji's travels', 1927)

Largely forgotten today, Daisuke Ito was regarded in the late 1920s and early 1930s, by

Japanese audiences and critics alike, as one of Japan's foremost directors. Most of his

films from that period are unfortunately now lost, and, except for a few fragments and the

miraculously surviving Oatsurae Jirokichi goshi ('The chivalrous robber Jirokichi', 1931),

all his silent films were known after the war only by repute. But in December 1991 his

most famous silent film was rediscovered, and some of the second part and most of the

third part of the great trilogy Chuji tabi nikki ('A diary of Chuji's travels', 1927) became

available for modern audiences to enjoy.

Ito made his first film in 1924 and thereafter worked consistently as a director until 1970.

But it is on his silent films that his reputation is founded, and except for one or two works

such as Oosho ('The chess king', 1948) his sound films, particularly post-war, have been

undervalused. The main reason for this is that critics have tended to judge them (rather as

happened in the case of Abel Grance in France) against a fading memory of his innovative

silent style. The energetic style of his late 1920s films was indeed unique in the world.

The camera roamed in every direction, samurai dashed across the screen, a row of

lanterns swirled around in the deep dark of night, and the rhythm of the films reached

vertiginous speeds through accelerated montage. Intertitles that stressed the dialogue were

synchronized to the rhythm of the images, and the rhythm of the words was inspired by

Japanese poetry and other forms of story-telling.

Above all, a spirit of Romanticism, sentimentalism, nihilism, and a despairing rebellion

against power penetrated all of Ito's films of the period. He raised the jidaigeki (period

drama) to the level of avant-garde cinema, even competing with the so-called tendency

film (expressing proletarian ideology). Some of his jidaigeki borrowed materials from

German or French novels. Elsewhere, he repeatedly tried to break out of the established

formula for jidaigeki films, including an attempt to conjure up images inspired by

Chopin's music in Ikiryo ('Evil spirit', 1927). In the early 1930s, like Alfred Hitchcock, he

experimented with sound. In his first sound film, Tangesazen ( 1933), he deliberately

restricted the use of dialogue and sound, and he used Schubert's Unfinished Symphony in

a jidaigeki - Chusingura ('The loyal forty-seven Ronin', 1934).

Ito always saw himself as an artisan, and his work of the sound period contains its fair

share of mediocre entertainment films made to the orders of producers. His wartime work,

such as Kurama Tengu ( 1942) or Kokusai mitsuyudan ('International smugglers', 1944),

provided an escape from the reality of war as well as from the propaganda film.

He returned to the front rank of Japanese cinema in 1948 with the highly acclaimed

Oosho, but apart from a few films, such as Hangyakuji ('The conspirator', 1961), his post-

war work remains largely unrecognized. Among his lesser-known films Yama wo tobu

hanagasa ('The hat adorned with flowers flying over the mountain', 1949) is undoubtedly,

from a modern standpoint, a masterpiece, as is Harukanari haha no kuni ('The motherland

far far away', 1950), with its contrapuntal editing of image and sound and use of

metaphorical montage.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s Ito made many jidaigeki, and came to be regarded as a

director of a single genre of film. His early career as maker of highly prized silent films

became forgotten, as did the films themselves. But he is now beginning to be rediscovered

and valued, both for his masterly silent films and for the qualities of mise-en-scène in his

sound films.

HIROSHI KOMATSU SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

Jogashima ( 1924); Ikiryo ( 1927); Oatsurae Jirokichi goshi ( 1931); Tangesazen ( 1933);

Chusingura ( 1934); Kokusai mitsuyudan ( 1944); Oosho ( 1948); Yama wo tobu

hanagasa ( 1949); Harukanari haha no kuni ( 1950); Hangyakuji ( 1961)

THE SILENT CINEMA EXPERIENCE

Music and the Silent Film

MARTIN MARKSSilent films were a technological accident, not an aesthetic choice. If

Edison and other pioneers had had the means, music would probably have been an

integral part of filmmaking from the very start. But because such means were lacking, a

new type of theatrical music rapidly developed; the wide variety of films and screening

conditions in Europe or America between 1895 and the late 1920s came to be matched by

an equally wide range of musical practice and musical materials. With the coming of

synchronized sound this variety disappeared and a whole past experience was lost from

view. Since the 1980s, however, with the renewed interest in reviving silent performance,

film musicians and historians have begun to rediscover the field and even to find new

forms of accompaniment for silent film.

MUSICAL PRACTICE

Music in silent cinema has long been of interest to film theorists, and a number of

explanations have been proposed to account for its apparently indispensable presence

right from the start. These have tended to concentrate on the psycho-acoustic functions of

music (well summarized by Gorbman 1987), and only recently have historians begun to

pay close attention to the theatrical context of film presentations and in particular to the

debt owed by film music to long-standing traditions of music for the theatre, adapted as

necessary to suit the new medium.Consider, for example, the remarkable variety and

richness of so-called 'incidental' music for stage plays throughout the nineteenth century

(a variety that becomes still richer if one looks further to the past). At one end, lavish

incidental works by Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Bizet, and Grieg, though somewhat

atypical, proved highly useful for film accompaniment -- or so we can presume, since

excerpts from these works were repeatedly published in film music anthologies and

inserted into compiled scores (often for scenes quite unlike their original contexts). But

most theatre music was the work of minor figures, who, like their successors in the field

of film music, continually had to compose, arrange, conduct, or improvise functional bits

and pieces -- 'mélodrames', 'hurries', 'agits', and so on-on the spur of the moment, for one

ephemeral production after another.Relatively little of this music is known today, but what

has been seen (like the collection of Victorian-period examples published by Mayer and

Scott) bears a strong family likeness to the seemingly 'new' music later published in film

anthologies. Thus, the practitioners of incidental music supplied a triple legacy -- of pre-

existent repertoire, stylistic prototypes, and working methods -just as did those who

specialized in the genres of ballet and pantomime. The latter genres sometimes came very

close to anticipating the peculiar requirements of scores for silent films, owing to their

absence of speech and need for continuous music, some of it consisting of closed forms