The Parthenon Enigma (18 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

This is why the famous oath said to have been sworn by the Greeks just before the

Battle of Plataia in 479 included this line: “I will not rebuild a single one of the shrines that the barbarians have destroyed but will allow them to remain for future generations as a memorial of the barbarians’ impiety.”

14

Though the authenticity of this oath has been questioned, its citation in both the literary and the epigraphic records suggests that it was real.

15

So, too, does archaeological evidence, which shows no major building initiatives on the Acropolis between 480 and 447

B.C.

But, as

Manolis Korres has stressed, this pledge was probably motivated as much by a need to restore Athenian solvency as by the totemic power of the ruins.

16

Rebuilding could not take place until Athens was on a stable financial footing, and this would take time.

Fighting with the

Persians, in fact, continued after the Athenian victory at Plataia, as the Greek allies attempted to dislodge the enemy from lands it had taken across the Aegean Islands, Thrace,

Asia Minor, Anatolia, and Cyprus. A confederation of Greek states was created in 478 for joint defense against the Persians, at first consisting largely of islanders but in time growing to include 150 to 170 member states. The island of

Delos in the very center of the Aegean made the perfect base for the organization that historians have labeled the

Delian League but in antiquity was simply called “the Greeks and their allies.” Member states contributed ships, timber, grain, and troops to the war effort. Finally, in 449

B.C.

, the Athenian ambassador

Kallias negotiated a peace with the Persians, ensuring freedom for the Greek cities of Asia Minor and prohibiting Persian satrapies (even Persian ships) anywhere in the Aegean.

17

This marked a watershed not only for the Greek confederation generally

but for the Athenians in particular, who were now launched on a new course toward empire.

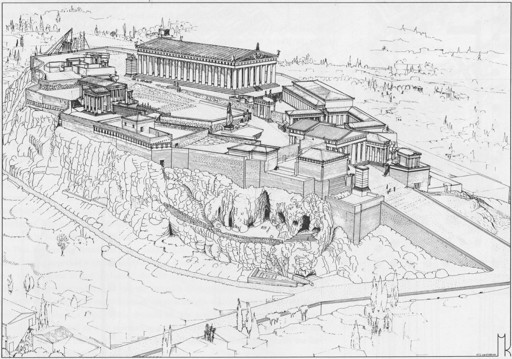

Perikles lost no time in turning to a long-deferred goal: the re

building of the Acropolis (below). With peace at hand, the unspent balance in the league’s treasury was no longer needed to fund the war. Perikles transferred five thousand talents into “Athena’s account,” which would now serve as a blank check for his vision. A monumental double gateway, the

Propylaia, would replace the former entrance at the west; the shrine of Athena Nike, just beside it, would be wholly reconfigured with a new marble temple surrounded by a sculptured parapet. The unfinished

Older Parthenon at the south of the plateau and what remained of the Old Athena Temple at the north would be renewed with the building of the Parthenon and the

Erechtheion. Every structure would be made from bright white Pentelic marble and enhanced with a dazzling profusion of carved decoration. It would cost a fortune.

Plutarch tells us that the extravagance of Perikles’s plan brought loud resistance in the citizen assembly, where critics accused him of squandering state funds.

18

Thucydides (not the historian but a man of the same name who was the political successor to Kimon) was one of those who railed most fiercely against Perikles. But the leader deftly parried all accusations, offering to cover the expenses himself, provided he be allowed to inscribe “Perikles built it” upon the sacred structures.

19

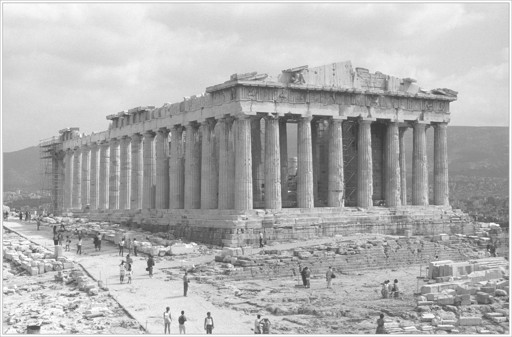

In the end, the citizen assembly acquiesced fully to their leader and his ambitious plans, allocating vast sums year after year to move the project forward. And move forward it did, creating the biggest, most technically astonishing, ornately decorated, and aesthetically compelling temple ever known (above).

Reconstruction drawing of the Athenian Acropolis, classical through Hellenistic periods, by M. Korres. (illustration credit

ill.26

)

Parthenon from northwest, 1987. (illustration credit

ill.27

)

First and foremost, this supremely

deisidaimoniacal people wanted to honor

Athena in the most spectacular way they could, thanking her for victory over the

Persians. Since more is more when it comes to

prayer, the Parthenon had to be excessive in its splendor. By now, an entire generation of Athenians had grown up never having known a grand and glorious Acropolis. And so, too, perhaps, the “Persian War teenagers” wanted to leave their own

children something more than a citadel in ruins, a barren ground zero that fossilized the bitter memories of defeat. It was time to forge a new narrative for the city, one of Athenian triumph and supremacy, a visual tribute to its miraculous rise from the ashes. Athens possessed all the necessary ingredients to achieve this: a strong leader, the collective will of the people, an abundance of talented

artists and artisans, access to quality marble, an exquisitely evolved aesthetic sensibility, optimism, manpower, and money, lots of it.

The Parthenon would be, among other things, a new home for the treasury of the allied Greek states,

Perikles having shrewdly maneuvered the relocation of the funds from Delos to Athens in 454/453

B.C.

The previous year, when the Greek fleet had suffered a serious defeat by the

Persians in the waters off Egypt, Perikles used the setback as his pretext for moving the treasure to Athens, allegedly for safekeeping. With that, the confederation was suddenly transformed into what we call the

Athenian League. From the 460s on, more and more states contributed money rather than ships to the common pool of resources and it now fell to the Athenians alone to administer these funds. By 454, when Perikles effected the fund transfer, the balance stood at an extraordinary sum of 8,000 talents.

20

The allies would still have to collectively donate a total of 600 talents to Athens in annual tribute (roughly 17 tons of silver, worth something like $360 million in present value, though this is terribly difficult to figure).

21

A sixtieth of this tribute was reserved for the goddess

Athena herself and placed in a special account controlled, of course, by the Athenian state. We know that by 431

B.C.

, some 6,000 talents (170 tons of coined silver) were housed on the Acropolis, much of this within the Parthenon itself. The gold and ivory statue of Athena in fact served as a kind of vault (insert

this page

, bottom). Its robes were plated with 40 to 44 talents of solid gold, weighing twenty-three hundred to twenty-five hundred pounds. Piety permitted that the city could use this raiment as a line of credit, removing sections of the gold as needed, provided the debt was eventually repaid.

22

Thus, a staggering treasure came under Athenian control. It permitted the polis to build a peerless navy for defense of the Athenian League but also to advance Athenian self-interest, expanding its international trade and beautifying the Acropolis beyond all imagining. There were also those lavish benefits to individual citizens. In this process, Athenian hegemony over the confederation’s members evolved into the

Athenian Empire, reducing the other Greek members to subject peoples.

23

The Parthenon, a potent symbol of the growing wealth and power of this empire, attested to Athenian supremacy, feeding the city’s eternal appetite for competition with other states and nations. It was also, more literally, the place where the profits of lording it over foreign Greeks, the riches of allied tribute, were held. Inscribed inventories confirm a

burgeoning treasure.

24

Dedications wrought from gold, silver, and bronze, and fashioned from ivory, packed the Parthenon’s interior: weapons, vessels, lamps,

shields, furniture, boxes, baskets, jewelry,

musical instruments, statues, and other gifts for the goddess.

25

These filled the eastern cella (called the

hekatompedon

in the inventory lists) as well as the westernmost room (referred to as the

parthenon

). Built at a moment when civic

religion, self-regard, and imperial ambitions began to overtake Athenian thinking, the Parthenon, even in all its luxurious grandeur, was looked upon with sincerity and awe as the epicenter of the city’s most venerable ideals and virtues.

Perikles’s master plan for the Acropolis had yet another motivation: long-term employment for hundreds, if not thousands, of laborers. More than a hundred thousand tons of

marble needed to be quarried for the re

building of the Acropolis; seventy thousand blocks had to be cut and transported to the Sacred Rock, hauled to the top, where they would be finished by stonemasons, and set in place.

26

Roads had to be built up the slopes of Mount

Pentelikon for access to new quarries, as well as to Athens itself, some 16 kilometers (10 miles) to the southwest.

Manolis Korres has reconstructed the process of quarrying, cutting, and transporting the blocks (some weighing as much as thirteen to fourteen tons) to the city center.

27

Riggers and teamsters loaded the freshly hewn stones at the quarry onto wheeled carts and sledges pulled by oxen and horses for the six-hour journey along a flagstone road. A new ramp, broadened to 20 meters (66 feet) in width, was built up the

west slope of the Acropolis for hauling materials to the top. There, a team of as many as two hundred craftsmen worked on the marble, up to fifty sculptors carved the figured decoration, and any number of additional men labored on construction crews and support teams.

28

Thus, all citizens would share in the prosperity of the city. Plutarch expounds the litany of laborers employed in Perikles’s scheme: carpenters, modelers, metalworkers, stonemasons, dyers, gilders, ivory softeners, painters, embroiderers, and engravers, as well as the purveyors of all the materials needed and those who transported materials, including sailors, helmsmen, wagon makers, keepers of oxen, and muleteers. In addition, rope makers, linen weavers, leather workers, road builders, and quarrymen were needed, plus a host of unskilled laborers to support all the others. “The requirements of these projects,” Plutarch observes, “divided and distributed surplus money to pretty well every age-group

and type of person.”

29

The citizenry of Athens would be employed not only for the sixteen-year period of the Parthenon’s construction and adornment (447–432

B.C.

) but also for the time it took to build the

Propylaia (437–432), the

Erechtheion (421–405), and the

temple of Athena Nike (427–409). Indeed, full employment, thanks to Perikles’s vision, lasted well past his death, into the last decade of the fifth century.

Inscribed accounts listing payments to these workers, as well as expenditures for construction materials, suggest that the total

cost of the Parthenon was around 469 silver talents (something like $281 million today).

30

This was paid, in part, with revenues from the

silver mines at

Laureion but largely from Athena’s own coffers, those fed by allied tribute. A financial committee of six Athenians and a scribe was elected annually to administer the payment of a vast array of expenses for the construction of the temple.

The accounts also tell us that construction of the Parthenon began in 447/446

B.C.

, that its gold and ivory statue of Athena was dedicated at the Great Panathenaia of 438, and that work was completed in 433/432, when the larger-than-life-size figures were finally set within the pediments.

31

It seems that, like so many construction projects before and since, the building wasn’t quite finished in time for its scheduled dedication. Nonetheless, the superstructure was up, the roof was on, and sculptured figures could easily be placed in the pediments five years later. The exquisite quality of the carving of these figures confirms that the extra time was well spent (

this page

). And it is nevertheless astonishing that the superstructure alone was fully standing in just nine years. Athenian naval technology no doubt contributed to the speed with which the building went up.

32

Knowledge of lines, winches, blocks, and pulleys for the hoisting of sails and lifting of cargo was easily transferred to hauling and lifting

marble column drums and cornice blocks.

33