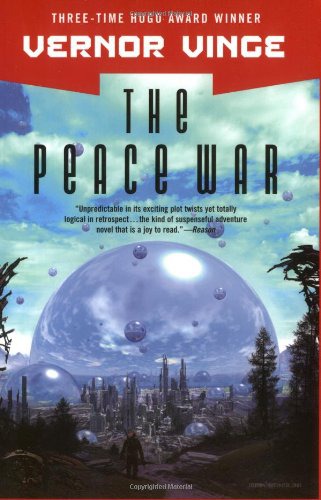

The Peace War

Authors: Vernor Vinge

Tags: #Science fiction, #General, #Fiction, #Fiction - Science Fiction, #Science Fiction - General, #Technology, #Political, #Political fiction, #Technology - Political aspects, #Inventors, #Political aspects, #Power (Social sciences)

ACROSS REALTIME

ACROSS REALTIMECopyright © 1991 by Vernor Vinge

To my parents,

Clarence L. Vinge and Ada Grace Vinge,

with Love.

Flashback

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Flashforward

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Flashforward

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Flashforward

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

One hundred kilometers below and nearly two hundred away, the shore of the

Beaufort Sea didn't look much like the common image of the arctic: Summer was far

advanced in the Northern Hemisphere, and a pale green spread across the land, shading

here and there to the darker tones of grass. Life had a tenacious hold, leaving only an

occasional peninsula or mountain range gray and bone.

Captain Allison Parker, USAF, shifted as far as the restraint harness would permit,

trying to get the best view she could over the pilot's shoulder. During the greater part of

a mission, she had a much better view than any of the "truck-drivers," but she never

tired of looking out, and when the view was the hardest to obtain, it became the most

desirable. Angus Quiller, the pilot, leaned forward, all his attention on the retrofire

readout. Angus was a nice guy, but he didn't waste time looking out. Like many pilots —

and some mission specialists — he had accepted his environment without much

continuing wonder.

But Allison had always been the type to look out windows. When she was very

young, her father had taken her flying. She could never decide what would be the most

fun: to look out the windows at the ground-or to learn to fly. Until she was old enough

to get her own license she had settled for looking at the ground. Later she discovered

that without combat aircraft experience she would never pilot the machines that went as

high as she wanted to go. So again she had settled for a job that would let her look out

the windows. Sometimes she thought the electronics, the geography, the espionage

angles of her job were all unimportant compared to the pleasure that came from simply

looking down at the world as it really is.

"My compliments to your autopilot, Fred. That burn puts us right down the slot."

Angus never gave Fred Torres, the command pilot, any credit. It was always the

autopilot or ground control that was responsible for anything good that happened when

Fred was in charge. Torres grunted something similarly insulting, then said to Allison,

"Hope you're enjoying this. It's not often we fly this thing around the block just for a

pretty girl."

Allison grinned but didn't reply. What Fred said was true. Ordinarily a mission was

planned several weeks in advance and carried multiple tasks that kept it up for three or

four days. But this one had dragged the two-man crew off a weekend leave and stuck

them on the end of a flight that was an unscheduled quick look, just fifteen orbits and

back to Vandenberg. This was clearly a deep range, global reconnaissance — though

Fred and Angus probably knew little more. Except that the newspapers had been pretty

grim the last few weeks.

The Beaufort Sea slid out of sight to the north. The sortie craft was in an inverted,

nose-down attitude that gave some specialists a sick stomach but that just made Allison

feel she was looking at the world pass by overhead. She hoped that when the Air Force

got its permanent recon platform, she would be stationed there.

Fred Tomes — or his autopilot, depending on your point of view — slowly pitched the

orbiter through 180 degrees to bring it into entry attitude. For an instant the craft was

pointing straight down. Glacial scouring could never be an abstraction to someone who

had looked down from this height: the land was clearly scraped and grooved like ground

before a dozer blade. Tiny puddles had been left behind: hundreds of Canadian lakes, so

many that Allison could follow the sun in secular glints that shifted from one to another.

They pitched still further. The southern horizon, blue and misty, fell into and then out

of view. The ground wouldn't be visible again until they were much lower, at altitudes

some normal aircraft could attain. Allison sat back and pulled the restraint more tightly

over her shoulders. She patted the optical disk pack tied down beside her. It contained

her reason for being here. There were going to be a lot of relieved generals-and some

even more relieved politicians-when she got back. The "detonations" the Livermore

crew had detected must have been glitches. The Soviets were as innocent as those

bastards ever were. She had scanned them with all her "normal" equipment, as well as

with deep penetration gear known only to certain military intelligence agencies, and had

detected no new offensive preparations. Only...

...Only the deep probes she had made on her own over Livermore were unsettling.

She had been looking forward to her date with Paul Hoehler, if only to enjoy the

expression on his face when she told him that the results of her test were secret. He had

been so sure his bosses were up to something sinister at Livermore. She now saw that

Paul might be right; there was something going on at Livermore. It might have gone

undetected without her deep-probe equipment; there had been an obvious effort at

concealment. But one thing Allison Parker knew was her high-intensity reactor profiles,

and there was a new one down there that didn't show up on the AFIA listings. And she

had detected other things — probe-opaque spheres below ground in the vicinity of the

reactor.

That was also as Paul Hoehler had predicted.

NMV specialists like Allison Parker had a lot of freedom to make ad lib additions to

their snoop schedules; that had saved more than one mission. She would be in no

trouble for the unscheduled probe of a US lab, as long as a thorough report was made.

But if Paul was right, then this would cause a major scandal. And if Paul was wrong,

then

he

would be in major trouble, perhaps on the road to jail.

Allison felt her body settle gently into the acceleration couch as creaking sounds came

through the orbiter's frame. Beyond the forward ports, the black of space was beginning

to flicker in pale shades of orange and red. The colors grew stronger and the sensation of

weight increased. She knew it was still less than half a gee, though after a day in orbit it

felt like more. Quiller said something about transferring to laser comm. Allison tried to

imagine the land eighty kilometers below, Taiga forest giving way to farm land and then

the Canadian Rockies — but it was not as much fun as actually being able to see it.

Still about four hundred seconds till final pitch-over. Her mind drifted idly, wondering

what ultimately would happen between Paul and herself. She had gone out with better-looking men,

but no one smarter. In fact, that was probably part of the problem. Hoehler

was clearly in love with her, but she wasn't allowed to talk technical with him, and what

nonclassified work he did made no sense to her. Furthermore, he was obviously

something of a troublemaker on the job — a paradox considering his almost clumsy

diffidence. A physical attraction can only last for a limited time, and Allison wondered

how long it would take him to tire of her — or vice versa. This latest thing about

Livermore wasn't going to help.

The fire colors faded from the sky, which now had a faint tinge of blue in it. Fred — who

claimed he intended to retire to the airlines — spoke up, "Welcome, lady and gentleman, to

the beautiful skies of California... or maybe it's still Oregon."

The nose pitched down from reentry attitude. The view was much like that from a

commercial flyer, if you could ignore the slight curvature of the horizon and the darkness

of the sky. California's Great Valley was a green corridor across their path. To the right,

faded in the haze, was San Francisco Bay. They would pass about ninety kilometers east

of Livermore. The place seemed to be the center of everything on this flight: It had been

incorrect reports from their detector array which convinced the military and the

politicians that Sov treachery was in the offing. And that detector was part of the same

project Hoehler was so suspicious of — for reasons he would not fully reveal.

Allison Parker's world ended with that thought.

The Old California Shopping Center was the Santa Ynez Police Company's biggest

account — and one of Miguel Rosas' most enjoyable beats. On this beautiful Sunday

afternoon, the Center had hundreds of customers, people who had traveled many

kilometers along Old 101 to be here. This Sunday was especially busy: All during the

week, produce and quality reports had shown that the stores would have best buys. And it

wouldn't rain till late. Mike wandered up and down the malls, stopping every now and

then to talk or go into a shop and have a closer look at the merchandise. Most people

knew how effective the shoplift-detection gear was, and so far he hadn't had any business

whatsoever.

Which was okay with Mike. Rosas had been officially employed by the Santa Ynez

Police Company for three years. And before that, all the way back to when he and his

sisters had arrived in California, he had been associated with the company. Sheriff Wentz

had more or less adopted him, and so he had grown up with police work, and was doing

the job of a paid undersheriff by the time he was thirteen. Wentz had encouraged him to

look at technical jobs, but somehow police work was always the most attractive. The

SYP Company was a popular outfit that did business with most of the families around

Vandenberg. The pay was good, the area was peaceful, and Mike had the feeling that he

was really doing something to help people.

Mike left the shopping area and climbed the grassy hill that management kept nicely

shorn and cleaned. From the top he could look across the Center to see all the shops and

the brilliantly dyed fabrics that shaded the arcades.

He tweaked up his caller in case they wanted him to come down for some traffic

control. Horses and wagons were not permitted beyond the outer parking area. Normally

this was a convenience, but there were so many customers this afternoon that the owners

might want to relax the rules.

Near the top of the hill, basking in the double sunlight, Paul Naismith sat in front of his

chessboard. Every few months, Paul came down to the coast, sometimes to Santa Ynez,

sometimes to towns further north. Naismith and Bill Morales would come in early

enough to get a good parking spot, Paul would set up his chessboard, and Bill would go

off to shop for him. Come evening, the Tinkers would trot out their specialties and he

might do some trading. For now the old man slouched behind his chessboard and

munched his lunch.

Mike approached the other diffidently. Naismith was not personally forbidding. He

was easy to talk to, in fact. But Mike knew him better than most — and knew the old man's

cordiality was a mask for things as strange and deep as his public reputation implied.

"Game, Mike?" Naismith asked.

"Sorry, Mr. Naismith, I'm on duty. "Besides, I

know you never lose

except on purpose.

The older man waved impatiently. He glanced over Mike's shoulder at something among

the shops, then lurched to his feet. "Ah. I'm not going to snare anyone this afternoon.

Might as well go down and window shop."

Mike recognized the idiom, though there were no "windows" in the shopping center,

unless you counted the glass covers on the jewelry and electronics displays. Naismith's

generation was still a majority, so even the most archaic slang remained in use. Mike

picked up some litter but couldn't find the miscreants responsible. He stowed the trash

and caught up with Naismith on the way down to the shops.

The food vendors were doing well, as predicted. Their tables were overflowing with

bananas and cacao and other local produce, as well as things from farther away, such as

apples. On the right, the game area was still the province of the kids. That would change

when evening came. The curtains and canopies were bright and billowing in the light

breeze, but it wasn't till dark that the internal illumination of the displays would glow and

dance their magic. For now, all was muted, many of the games powered down. Even

chess and the other symbiotic games were doing a slow business. It was almost a matter

of custom to wait till the evening for the buying and selling of such frivolous equipment.