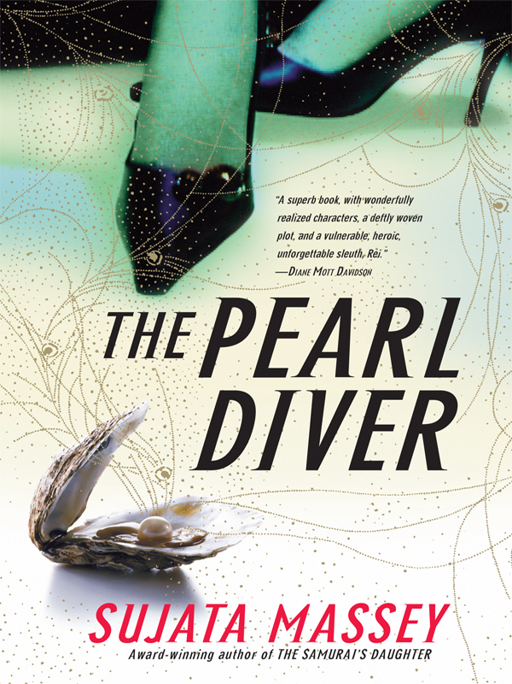

The Pearl Diver

Authors: Sujata Massey

Sujata Massey

I’d scored a single line and a shadow.

“We’re very excited about Bento,” Marshall Zanger said in his…

I’d thought that the month until the opening of Bento…

Justin brought me a second cocktail, but I didn’t touch…

I was glancing back at the kitchen, trying to decide…

It was too early to call San Francisco to give…

I had just finished talking to Martina about the press…

A night with Kendall and the kids. I had no…

“No way!” I said, and looked at Andrea, really looked…

Hugh was coming out of customs, the zone in Dulles…

While driving through the Virginia countryside a few hours later,…

“Of course I remember where the house is,” Andrea said…

We left half an hour later. I’d tried to linger,…

In Bethesda, we bombed out at Claire Dratch’s salon because…

Now I was happy that we were going to Bento…

Bento’s kitchen felt like a greasy version of a steam…

Plum Ink was upscale Chinese: glass-and-chrome tables, leather seating, and…

When you pack a car trunk, there’s never enough room,…

“She is waking.”

Three days after the ride back to Washington, I still…

I’d been consuming regular amounts of Aleve and irregular amounts…

Norie was tired after our venture to Bento, which meant…

I checked the other closet, just to make sure that…

Our strained silence was finally broken by the sound of…

Even after Norie and I put the letters away and…

Traffic patterns had changed and had become downright terrible, I…

From H Street, it was less than two minutes to…

For a restaurant that was supposed to be on its…

Just outside could mean a nearby town, or another country.

After I dropped my aunt off at the airport the…

As I drove away, I began to worry that Win…

My thoughts in a jumble, I drifted out of the…

I needed more. I went back to the reference historian…

“You poor thing.” I felt the hand in my hair…

I grabbed the tin of paste wax from under the…

I awoke around eleven, when I heard a TV comedy…

It was so silent in the freezer. Silent, and freezing.

“Who taught you to throw like that?” Hugh asked me…

The marine center was a modest two-story cinder-block building that…

R

EI

S

HIMURA

. A young antiques expert who is hoping to put an unsavory past in Tokyo behind her in exchange for a fabulous future in Washington, D.C.

H

UGH

G

LENDINNING

. Rei’s live-in boyfriend who practices law and pillow-book maneuvers in the hope of getting Rei to the altar.

K

ENDALL

H

OWARD

J

OHNSON

. Rei’s Washington cousin, a former fund-raiser married to the preppy realtor Win Johnson and busy raising their twin toddlers, Jacquie and Win Junior.

H

ARP

S

NOWDEN

. A California senator with a taste for Asian food and an eye on the White House. His press attaché, Martina, keeps him in line.

M

ARSHALL

Z

ANGER

. A restaurant entrepreneur in Washington who has deep pockets and deeper expectations of everyone.

J

IRO

T

AKEDA

. A former

Iron Chef

participant turned executive chef for Marshall’s two restaurants, Mandala and Bento.

A

NDREA

N

ORTON

. Bento’s hostess, a Washington girl-about-town famous for her looks and attitude. Her mother’s whereabouts are unknown, but her father, R

OBERT

N

ORTON

, and his second wife, L

ORRAINE

, and son, D

AVON

, live in rural central Virginia.

A

LBERTO

. A prep cook who keeps his eyes open and ears peeled.

P

HONG

. A bartender who makes wicked drinks.

J

USTIN

. A waiter with ambitions.

L

OUIS

B

URNS

. A homicide detective on the Washington, D.C., police force.

N

ORIE

S

HIMURA

. Rei’s beloved aunt from Yokohama, who has a legendary

yosenabe

recipe and a yen for murder.

P

LUS

a motley crew of cooks, waiters, police, watermen, and war veterans.

Their wedding was supposed to mark the beginning of spring, but it felt like winter. It was a small gathering, and everyone present looked cold—the men in their stiff uniforms and suits, and their women wearing spring dresses in candy colors.

Instead of a lacy, white American gown, the bride had chosen a wedding kimono. It was not a handed-down one, like so many people expected, but a brand-new one: red-and-orange silk brocade that shimmered with embroidered pairs of ducks, the sign of conjugal bliss. It had come from the Ginza, a district filled with enthralling boutiques that she could never have afforded until he’d come along—but shops where they weathered disapproving glares and hissed insults.

It didn’t matter anymore. Here she was on the edge of the water, the water that stretched all the way from her country to his; the water that he’d flown over to discover her, and to love her. And in the new country she would be valued more than just for her toughness in cold water.

When it was time to put the rings on each other’s fingers, she rushed so quickly that she accidentally dropped his. The guests laughed gently as he caught it, just before it hit the sand. She slid the ring on his finger, and he did the same for her. When they were done, he squeezed both her hands warmly. She paused, not

sure if this was proper procedure, and he smiled a little, as if to let her know he’d gotten carried away.

I do, she said. In two tiny words, she promised to love and honor in sickness and in health. He promised to do the same for her. It all seemed so incredible: the chilly, wild shoreline; the man beside her; the fact that she was finally getting married.

He was kissing her now, as he’d done a thousand times before, but in front of all these people. For a moment she froze in fear, because at the start of the ceremony, when she’d scanned the crowd to see who had come, she’d noticed the two men she didn’t like—the men who had suddenly appeared one evening a few months ago with a heavy black suitcase. Their voices had been harsh, and she’d quickly fled to the bedroom and shut the door, not wanting to know. She’d been so relieved when they’d gone a few hours later, but the feeling they’d left behind was bad. Why had they come to the wedding? She couldn’t imagine that he would have invited them.

The world wasn’t perfect, she thought as she closed her eyes and returned to the kiss. But now, she was no longer the girlfriend, on the outside. She was the wife. And if she used her newfound powers, she could find a way to make those men go away.

I’d scored a single line and a shadow.

Or were they double lines? I squinted at the plastic wand lying on the edge of the bathroom sink. One line meant negative, two positive. There was no definition for one line and the vague suggestion of a shadow.

“What’s the verdict? I’m about to dash,” Hugh called from the other side of the door.

“Inconclusive,” I said, opening the door and holding out the EPT stick like an obscene hors d’oeuvre. “You do the math.”

“One. That’s easy.”

“Don’t you see that shadowy line next to it?”

“A line would be pink. That’s just a wrinkle in the material.” He was already pulling on his Burberry. It was early spring in Washington and had rained for almost a solid week.

“I wish there was an explanation for shadows—”

“Shadows that only you can see. Darling, if you’re really anxious, you could call the consumer help line.”

“If I do that, I’m sure they’ll tell me to consult my doctor.”

“Maybe this means you’re a little bit pregnant.” Hugh paused in putting on his coat and slipped his hand inside my flannel pajamas to stroke my bare stomach.

“A surprise pregnancy would be a delight, without even a wedding date on the horizon,” I said, removing his hand. Hugh and I had been engaged for exactly three months. We had considered a quickie elopement, on the beach in Hawaii, but once our families had gotten wind of the idea, they’d guilt-tripped us out of it. Now we thought we should set the wedding in Washington. But progress was slow. I didn’t know the area well and was totally stymied about locations and caterers. I had nothing to show for myself except the guy.

“My cousin was married with new baby in arms and it was the best wedding anyone had been to in years,” Hugh said, spinning his rolled-up umbrella through the air before catching it neatly. He was such an optimist: about babies, about the outcome of the class-action suit he was trying to organize, about life in general. He didn’t even mind the Washington rain, because it reminded him of Edinburgh. I preferred the hard, blinding rain that made a rock-and-roll sonata on the tile roofs in Japan in the fall, or the warm, humid rains that marked spring’s rainy season. But I’d take the Washington rain, because it came with Hugh, and the promise of our future.

After we negotiated the night’s dinner plan—risotto with browned onions and sea scallops if I could find them, and a simple green salad—Hugh left, and I made myself a quick

o-nigiri

. I’d kept last night’s rice warm in the rice cooker, and I had a small piece of leftover salmon in the fridge. I tucked the salmon into the rice and folded the triangular wedge into a sheet of seaweed that I quickly roasted on the stove.

I ate the rice ball with my left hand and used my right to scroll through the

Daily Yomiuri

online. I’d been away from Japan about six months now, and I could feel the language beginning to slip. It was my duty as a

hafu

—a half-Japanese, half-American—to keep up. I bypassed woeful economic news and went straight to the language-teaching column aimed at foreigners. The word of the day was

zurekin

, which meant “off-peak commuting,” an idea strongly encouraged by the government but not quite adopted by

the working world. It was easier, calmer, better for people and the environment

At least, that’s how it sounded on paper. My whole life had gone from frenetic to

zurekin

—and I wasn’t sure I liked it. I’d spent my twenties working in Japan, where I’d lived simply and worked hard, and come to believe that everything Japanese was wonderful, even the crowded trains. The problem was, I couldn’t live in Japan anymore. I’d been thrown out, for an indefinite length of time, by the government for a misdeed I’d committed in the name of something more important. Now, because of the black mark in my passport, I had to make the best of it in Washington, complaining like all the other Washingtonians about crowded Metro trains that I considered only half-full, and so on. The only thing I truly agreed with was that Washington real estate was as insanely priced as Tokyo’s—though the spaces were bigger.

Hugh’s apartment, for instance, a two-bedroom on the second floor of an old town house, had lots to admire—high ceilings, old parquet floors, a bay window in the living room. It was lovely, but so…foreign. The telephone rang, and even that sounded different. I picked it up.

“Hi, honey, what are you doing for lunch?” The throaty voice on the other end of the line belonged to my cousin Kendall Howard Johnson, who lived in Bethesda.

“Kendall?” It annoyed me when people didn’t introduce themselves on the phone.

“Yes, Rei.” She drew my name out in the exaggerated way she’d pronounced it since we were little. Raaay, it sounded like.

Kendall had grown up in Bethesda, so I’d run into her plenty of times on my childhood visits to my mother’s home forty minutes to the north, in Baltimore. Grandmother always called Kendall and me the ladybug team because of Kendall’s red and my black hair; a set of cousins the same age who seemed destined to go together, but didn’t really. I’d never forget the humiliation of the summer when Kendall was fifteen and she’d taken me in the backyard bushes and produced a joint. I hadn’t known how to strike a match, let alone

inhale, and I was from the Bay Area, where everyone was supposed to know how to roll. But at the coed boarding school Kendall went to in Virginia, she’d already learned lots of things that I hadn’t. Horseback riding, joint rolling, how to sneak backstage at concerts without being stopped. Kendall, who’d worked as a corporate fund-raiser for a few years after college graduation, was always more advanced than I, and she’d maintained her advantage. The trust fund our grandmother had set up was now open for her use. Kendall dipped into it for her wedding, her first house payment, and even political donations that she’d begun to make as she began her careful ascent in grown-up Washington. My mother hinted that if I spent more time with my grandmother, she’d feel more benevolent toward me, but the fact was, I didn’t feel comfortable with Grand, as everyone called her, and the last thing I wanted to do was suck up to her for the money that all the Maryland cousins received, and that I, the lone Californian who hardly ever visited, didn’t. Then again, my exclusion from the trust might have occurred because my mother had jumped into a marriage that had felt like a death blow to the Howards. If my father had been black, the marriage would have broken Maryland law at that time. An Asian husband wasn’t quite as shocking as a black one, but my parents’ wedding hadn’t been a family affair.

Still, I couldn’t resent Kendall for being one of the Howards, for as busy as my cousin was with the babies, running her household, and fund-raising for her favorite political hopefuls, she hadn’t forgotten me. Kendall was the only relative who’d sought me out since I’d arrived in Washington a few months earlier, and I was grateful for that.

“How are the twins?” I avoided asking about her husband, Win, whom I couldn’t stand. Win was a real estate agent and saw everyone as a potential target. The fact that Hugh and I hadn’t been interested in buying a McMansion in the suburbs was still a point of contention.

“The babies are sick with strep. It’s highly unusual in children under three, but my two have it, of course!”

“You must be tearing out your hair running from one to the other,” I sympathized.

“At night, yes. By day our au pair is playing Nursie, thank goodness. I’ve escaped to the gym and had an hour to spin and then an hour for weights. I’m starved. Could you make a twelve-thirty lunch?”

“I don’t know. The weather’s kind of bad. I was thinking of doing some things around the apartment—”

“Rain’s good for you, honey!” Kendall snorted. “And it’s not just a gals’ lunch at the coffee shop I’m talking about. It’s at a good restaurant with Harp Snowden.”

“You socialize with Harp Snowden?” I was amazed. Harp Snowden was a Democratic senator representing California, a liberal stalwart who voted against each and every war proposed. He was one of the few politicians who’d entered the new century unabashedly pro-environment, pro-immigrant, pro-peace. Kendall’s meeting with him was interesting; she was a conservative Democrat, practically Republican.

“It’s a new relationship. When he suggested lunch at Mandala—one of my favorite places—I knew he was on the make. I thought you might like to come along, too.”

“What do you mean, he’s on the make?” I asked. Kendall had been married for five years. I’d thought she was still crazy about Win.

“Not that way, silly. He wants me to raise money for him, you know, get involved with his campaign in this area, especially reaching into northern Virginia. It’s kind of a challenge, not being a Republican there, although he does have the history of actually having fought in Vietnam and lost a foot, which earned him the Silver Star and a Purple Heart. He’s kind of like John McCain meets Howard Dean meets the late Paul Wellstone.”

Kendall was like that. She talked in shorthand, clichés, expressions that I was just beginning to learn everyone used, 24/7, in America. “But you’re from Maryland,” I said. “And if Senator Snowden and you are both Democrats, what are you doing talking about going after Republicans?”

“It’s possible to get people to shift their vote, if the candidate is right,” Kendall said. “Of course I’m a Marylander, but I went to boarding school and college in Virginia, which practically makes me a citizen. I know everyone, from the horsey set in Charlottesville to the techies in Reston. Harp desperately needs a friend like me.”

Everyone

meant people with money, I thought cynically. “So how much money do you have to give the senator to become his friend?”

“An individual can’t give more than two grand because of all the soft-money reforms, but people like me can encourage our friends to give money. Lots of people, lots of money. You weren’t here during the McCain campaign, but I threw a dinner for him that people are still talking about.”

“McCain wasn’t a Democrat,” I pointed out. “What are you, a switch-hitter?”

“Usually I describe myself as a conservative Democrat with independent leanings,” Kendall said. “Anyway, I promise you lunch won’t be too political. I want you to relax. You can talk with him about Japan. He did some kind of Zen yoga thing there when he was in his twenties. Maybe you have some friends in common.” She paused. “Oh, Rei. About your clothes?”

“Yes. What should I wear?” A private lunch with a senator was a first for me.

“Think Democrat, but dress Republican. Got it?”

I went through my closet furiously that morning, tossing clothes left and right as I searched for the outfit that Kendall had in mind. At one time, I had many conservative skirts and blazers from Talbots, but Hugh had encouraged me to toss them after I’d left my old life as a teacher. Now I wore sexier, casual things—leather jeans, blue jeans, T-shirts, miniskirts, boots. I also had a magnificent collection of cast-off clothing of my mother’s that spanned the sixties to the nineties. The clothes were well made and beautiful, but none of them was Reagan Red or Bush Blue—after all, my mother was a

lefty, too—but in the end, I settled on a cream Ultrasuede pantsuit worn with a black camisole. Looking at myself in the mirror after I’d belted its jacket, I appeared unhappily thick in the middle. Since returning to the States, I’d rekindled my love affair with bread and cheese. The scale said 121, which was horrific for someone who had hovered carelessly between 110 and 115 her entire life.

Still, the pants had an elastic waist, so I was able to wear them. I covered it all up with an aquamarine-colored raincoat that Kendall had made me buy a month earlier during a frenetic shopping expedition we’d made through White Flint Mall with her babies in tow. A raincoat was a necessity in Washington; it seemed as if it had rained all spring. Today was no exception. I hoisted my umbrella and left Hugh’s Edwardian apartment building on Mintwood Place. The neighborhood we lived in, Adams-Morgan, was a real hike from the Metro; Hugh had chosen it when he was a bachelor, for the restaurants and bars. He hadn’t thought twice about the twenty-minute walk to the Metro because he used a car to go to work downtown.

It was an odd habit, I thought, this insistence on driving a car in cities with public transportation.

Again, I was reminded of the city’s deficiencies. When Hugh had courted me, taking me to jazz clubs in Georgetown and coffee shops in Dupont Circle, I’d been charmed; but now that I’d more or less explored every inch of the nation’s capital, I felt otherwise. Sure, there were delightful late-nineteenth-century brick and stucco houses in Adams-Morgan, and you could dance at a real salsa bar, or get a reasonably priced Brazilian bikini wax from a real Brazilian, but that wasn’t enough to make a world-class city experience. Outside Adams-Morgan, the situation was even bleaker. Downtown Washington was a bore, a far cry from my birthplace of San Francisco, and Tokyo, my adopted hometown since college. In Washington, there was nowhere to browse, no scene. Large office buildings were interspersed with ugly chain stores and just a smattering of turn-of-the-century buildings that had gone to pot—literally, from the looks of some of the people lounging outside them.

As I emerged from the Metro Center station and headed toward Ninth, where Mandala was located, I passed a woman sitting on the steps of an old row house, a child between her knees and a Styrofoam cup at her side. I didn’t always give money to people who asked me for it, and the woman hadn’t even looked at me, let alone spoken. Yet I was overcome with guilt for what I’d just been thinking about Washington. I dropped a dollar in the cup, but only the child looked at me. She had a typically round child’s face, but eyes that looked much older. She seemed to see through me, back to the wild salmon I’d had for breakfast, and the expensive meal that lay ahead. A dollar wasn’t much of a trade, but she nodded at me, and I nodded back.

I shivered, trying to put the moment behind me as I opened the heavy old temple door that led to Mandala. I hadn’t been here before, but Hugh had, for some business lunches, and he’d told me it was fantastic. Judging from the atmosphere alone, it was my kind of place. Flickering electric candles in iron sconces illuminated a gorgeous mosaic tile floor with a floral mandala in its center. The dining tables were made from old Chinese altar tables or doors, I thought after a moment of study. Everything was rubbed to a soft reddish sheen, and the waitstaff wore dark-red shantung Mao jackets over black pants. It was quite a scene, about a million miles removed from the rainy, drab world outside its oversized brass doors.