The Physics of Sorrow (16 page)

Read The Physics of Sorrow Online

Authors: Translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel Georgi Gospodinov

I race into the bomb shelter of the third person singular, I send another into the minefields of the past. I was that same person, who was once in first person, and now I’m afraid to ask whether he’s still alive. Are they still alive, all those we’ve been?

D

OUBLE

P

REPAREDNESS

1980. On the one hand, there was the apocalypse, the flood, the end of the world according to John and his grandmother. On the other hand, that toothy (and armed to the teeth) Jimmy Carter was lurking, with his cowboy hat, riding a Pershing missile, as he was drawn in his father’s newspaper. At school, the slide projector was constantly showing shots of that atomic mushroom cloud and he already carefully skirted any mushroom that happened to sprout up in the garden, as if it might explode under his sandals.

The two apocalypses—his grandmother’s and the school’s official one—didn’t coincide precisely, which only made matters worse. It clearly was a question of two different ends of the world, as if one weren’t enough. And a person had to be ready for each of them if he wanted to survive.

The preventative measures were also different. His grandma stopped slaughtering chickens, leaving that sin to weigh on his grandfather’s soul. According to her, a person had to constantly repent and avoid sins of any kind. To reduce his load, for some time he ceased his experiments with ants and tried not to hate so much that revolting creature Stefka, who sat in the desk behind him, who

never missed a chance to make fun of him for blushing. He couldn’t think of any other sins.

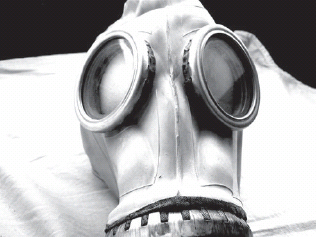

Defense against nuclear and chemical weapons was more complicated. You needed to put on your gas mask in no time flat. “In no time flat”—his Basic Military Training teacher’s favorite phrase. Then immediately add your cloak, rubber gloves, rubber boots, and hightail it to the nearest bomb shelter. Or if the bomb shelter is too far away, fall flat on your face in the direction opposite the nuclear blast, and don’t look at the mushroom cloud so as not to ruin your eyes. He knew everything, just as the rest of his classmates did, about the chemical weapons sarin, soman, mustard gas, and the havoc they wreaked. They had become experts on poison gases, chemical and biological weapons, atomic and neutron bombs, Pershing and cruise missiles.

So there wouldn’t be any surprises, he practiced for both scenarios. Whatever happens, put on your gas mask and start praying. During one of the drills, he tried to say a prayer with his gas mask on his head, but only a quiet rumbling could be heard through the hose, while the eyepieces of the tight rubber mask fogged up.

“What are you babbling to yourself about, greenhorn?” His military training teacher barked at him—he was a major, wore a uniform, and they were all afraid of him. “When you prattle on, you only use up your oxygen more quickly.”

Whoever managed to put on his gas mask in the allotted time—how many seconds was it?—would survive. Whoever didn’t, like Zhivka the Gimp, whose left arm was deformed, would be toast.

During recess, he would sit by himself at his desk, calculating whether his mother and father would make the cut-off. If they didn’t, why should he bother trying to survive? As for his grandma

and grandpa, they didn’t stand a chance, they were so slow. His grandma would first have to put on her glasses, she never knew where they were, then she’d have to find the bag with the gas mask, call to his grandpa, who was surely out somewhere with the cows . . .That definitely added up to more seconds than were allotted.

S

IDE

C

ORRIDOR

A person wearing a gas mask resembles a Minotaur.

D

EATH

I

S A

C

HERRY

T

REE

T

HAT

R

IPENS WITHOUT

U

S

Nothing will be destroyed by the bomb. The houses will remain intact, the school will remain intact, the streets and trees will still be there, and the cherry tree in the yard will ripen, only we won’t be there. That’s what they told us today in school about the aftermath of the neutron bomb.

—Notebook with instructions, 1980

Only now do I realize how precise that description is. The street is still there, the trees are still there, look, there’s the cherry tree, except we’re dead. Nothing is left of me, the erstwhile savior of the world. So that means somebody nevertheless dropped the neutron bomb. The absence of my grandmother, my grandfather, my father, my mother, and of that boy, about whom it’s difficult for me to speak in the first person, only serves to confirm this.

No one has yet thought up a gas mask and bomb shelter that protects against time.

T

IME

S

HELTER

The day after the Apocalypse, there won’t be any newspapers. How ironic. The most significant event in the history of the world will go unreported.

But it’s still beforehand. And I need to hurry . . . to finish my work.

A woman from Iran, sentenced to be stoned to death for adultery. Just don’t do it in front of my son, the woman says, having managed to give an interview to a European newspaper. A girl from Afghanistan on the cover of

Time

with her ears and nose cut off. The photo is shocking, a big black hole gapes where her nose should be.

A huge fire near Moscow, the suffocating smoke blankets the city, the number of victims rises every day. Floods in Europe. A deluge in Pakistan . . .

I copy down the newspaper headlines. The dates say August 2010. I’ve read similar news in the Old Testament and in some of the medieval chronicles. It would be interesting to make a journal out of newspaper headlines only. Flood . . . Fire . . . Cut off . . . I carefully fold the newspaper in half, then once again, then once again, until it is as small as a napkin and all that can be read of the words are . . . od . . . fi . . . off. I stuff it into a box labeled “Fragile.”

I’m trying to keep a precise catalogue of everything. For the time when “now” will be “back then,” as we wrote in our school yearbooks, liberally doused with the tears of our youth, which didn’t cost a thing. Good thing that the basement is big, an old bomb shelter, and despite all the stuff I’ve gathered up over the years, there’s still free space to be found. I insisted on that when buying the place. A nice, big cellar, a whole underground apartment, with two hallways, walls that form niches and secret passageways. I quizzed the owner at length about the thickness of the walls, the year the place was built, any past flooding, and so on. He was quite surprised. He must’ve regretted not raising the price a bit. Are you planning on living down here? No, I replied. And the next day I moved the most basic necessities for living into the basement. I spend most of my time down here. I feel at home. I mostly use the floor above as an alibi. If you put some effort into appearing normal, you can save yourself a lot of time, during which you can be what you want to be in peace.

In recent days the newspapers have reported that they’ve found the diaries of Dr. Mengele, who lived to a ripe old age in Latin America. Written between 1960 and 1975 in ordinary spiral-bound notebooks. Full of notes about the weather, short poems and philosophical musings, biographical details. An alibi for life itself, with all of its innocent details.

J

ANUARY

1

I’m not a hermit, I have a television downstairs (I only watch the evening news), I subscribe to thirty-odd newspapers and magazines, so I’m certainly no hermit. I still need to follow the world closely, I’m gathering signs.

I read Aristotle’s

Poetics

and listen to some surviving vinyl record.

It’s January 1 of the final year, according to some calendar. It’s too quiet, even for the afternoon of such a day. There aren’t the usual calls, texted greetings. I turn off my phone, to have an alibi for that silence.

In the newspapers I processed a while back, it said that “unfriend” was the word of the year for 2009. It feels like that’s all I’ve been doing these past ten years. Over time, friends have been disappearing in different ways. Some suddenly, as if they had never existed. Others gradually, awkwardly, apologetically . . . They stop calling. At first you don’t get it. Then you start checking to see whether your phone battery has died. A sharp absence at five in the afternoon. At first it lasts around an hour, then it gets shorter. But it never disappears. Just like with the cigarettes you quit smoking years ago, but which you keep dreaming about.

In the dying light of the day I once again feel that inrush of obscure sorrow and fear, true savage fear, for which I have no name. I quickly put on my coat, pull on a hat with ear flaps, I could easily pass as either hip or homeless, that suits me fine, I’m invisible in any case.

If anyone wants to see what his neighborhood will look like after the end of the world, he should go outside on the afternoon of January 1. Indescribable silence. All available reserves of joy have been spent the previous evening. Dry and cold, the rock bottom has been laid bare. Metaphysical rock bottom. I’ve always wondered what is actually being celebrated—the end of one year or the beginning of another. Most likely the end. If we were celebrating the beginning, then January 1 would be the happiest day.

I stroll through the narrow, icy pathways between the apartment buildings, some empty wine bottle rolls from beneath my feet, along with the remains of explosive devices of every caliber . . . And not a soul outside. This is starting to look suspicious. As if someone, under the cover of New Year’s fireworks, managed to blow everyone

away. They detonated that neutron bomb. I’m the only survivor, behind the thick walls of my hiding place. I can’t imagine there was anyone else cautious enough to have spent New Year’s Eve in a bomb shelter. I wonder what’s on CNN after the end of the world? I turn around to go check, and from the nothingness, two dogs and a bum jump out in front of me. The first living creatures . . . this year. I’m overjoyed to see them. Actually, this is their day, their New Year’s is a day later. When the previous night’s leftovers are thrown away and the dumpsters are overflowing like sad post-holiday malls.

T

O

B

E

O

PENED

A

FTER

. . .

An alarm clock, safety pin, toothbrush, doll, matchbox car, ladies’ hat, make-up kit, electric razor, cigarette case, pack of cigarettes, pipe, various scraps of cloth and fabric, one dollar in change, seeds for corn, tobacco, rice, beans, carrots . . .

What could hold a collection of such uncollectable things?

A suitcase, most likely. But who could be the owner of such a suitcase? The ladies’ hat suggests a woman, the pipe and the electric razor a gentleman, even though that’s no longer certain. Or the suitcase belongs to a little girl because of the doll, or perhaps a little boy because of the cars and all the odds and ends little boys tend to collect.

The list continues.

Novels, articles from

Encyclopaedia Britannica

, pictures by Picasso and Otto Dix,

Time

,

Vogue

,

Saturday Evening Post

,

Women’s Home Companion

, and other magazines and newspapers from the late summer of 1938. All of that on microfiche. The Bible in hardcopy. Short letters from Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann. The “Our Father” in 300 languages (!) and two standard English dictionaries . . .

A museum’s repository? A writer’s den?

To be continued . . .

A fifteen-minute film reel containing: a sound film with a speech by Roosevelt apropos of the season (the year is still 1938); a panoramic flight over New York; the hero of the most recent Olympic games, Jesse Owens; the May Day parade on Red Square in Moscow; shots from the undeclared war between Japan and China; a fashion show in Miami, Florida, from April; two girls in full-length bathing costumes, gentlemen in afternoon attire . . . And a diagram showing the location of the capsule, with the precise latitude and longitude with respect to the equator and Greenwich.

A time capsule, yes. With the world’s whole worrisome-cheerful schizophrenia, caught at a specific moment—on the eve of war, to boot.

That whole world was buried fifty feet underground on September 23, 1938, in perhaps the most famous capsule, designed by the engineers at Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company for the World’s Fair in New York. To be opened after 5,000 years. But exactly one year later, that world would be buried again (literally). This time without a ritual, without a capsule, and without a diagram showing the location.